Search the Community

Showing results for tags 'Chinese'.

-

An eG member recently asked me by private message about mushrooms in China, so I thought I'd share some information here. This is what is available in the markets and supermarkets in the winter months - i.e. now. I'll update as the year goes by. FRESH FUNGI December sees the arrival of what most westerners deem to be the standard mushroom – the button mushroom (小蘑菇 xiǎo mó gū), Agaricus bisporus. Unlike in the west where they are available year round, here they only appear when in season, which is now. The season is relatively short, so I get stuck in. The standard mushroom for the locals is the one known in the west by its Japanese name, shiitake, Lentinula edodes. They are available year round in the dried form, but for much of the year as fresh mushrooms. Known in Chinese as 香菇 (xiāng gū), which literally means “tasty mushroom”, these meaty babies are used in many dishes ranging from stir fries to hot pots. Second most common are the many varieties of oyster mushroom. The name comes from the majority of the species’ supposed resemblance to oysters, but as we are about to see the resemblance ain’t necessarily so. The picture above is of the common oyster mushroom, Pleurotus ostreatus, but the local shops aren’t common, so they have a couple of other similar but different varieties. Pleurotus geesteranus, 秀珍菇 (xiù zhēn gū) (below) are a particularly delicate version of the oyster mushroom family and usually used in soups and hot pots. 凤尾菇 (fèng wěi gū), literally “Phoenix tail mushroom”, Pleurotus pulmonarius, is a more robust, meaty variety which is more suitable for stir frying. Another member of the pleurotus family bears little resemblance to its cousins and even less to an oyster. This is pleurotus eryngii, known variously as king oyster mushroom, king trumpet mushroom or French horn mushroom or, in Chinese 杏鲍菇 (xìng bào gū). It is considerably larger and has little flavour or aroma when raw. When cooked, it develops typical mushroom flavours. This is one for longer cooking in hot pots or stews. One of my favourites, certainly for appearance are the clusters of shimeji mushrooms, Hypsizygus tessellatus. Sometimes known in English as “brown beech mushrooms’ and in Chinese as 真姬菇 zhēn jī gū or 玉皇菇 yù huáng gū, these mushrooms should not be eaten raw as they have an unpleasantly bitter taste. This, however, largely disappears when they are cooked. They are used in stir fries and with seafood. Also, they can be used in soups and stews. When cooked alone, shimeji mushrooms can be sautéed whole, including the stem or stalk. There is also a white variety which is sometimes called 白玉 菇 bái yù gū. Next up we have the needle mushrooms, . Known in Japanese as enoki, Flammulina velutipes are tiny headed, long stemmed mushrooms which come in two varieties – gold (金针菇 jīn zhēn gū) and silver (银针菇 yín zhēn gū)). They are very delicate, both in appearance and taste, and are usually added to hot pots. Then we have these fellows – tea tree mushrooms (茶树菇 chá shù gū), Agrocybe aegerita. These I like. They take a bit of cooking as the stems are quite tough, so they are mainly used in stews and soups. But their meaty texture and distinct taste is excellent. These are also available dried. Then there are the delightfully named 鸡腿菇 jī tuǐ gū or “chicken leg mushrooms”. These are known in English as "shaggy ink caps", Coprinus comatus. Only the very young, still white mushrooms are eaten, as mature specimens have a tendency to auto-deliquesce very rapidly, turning to black ‘ink’, hence the English name. Not in season now, but while I’m here, let me mention a couple of other mushrooms often found in the supermarkets. First, straw mushrooms (草菇 cǎo gū), Volvariella volvacea. Usually only found canned in western countries, they are available here fresh in the summer months. These are another favourite – usually braised with soy sauce – delicious! When out of season, they are also available canned here. Then there are the curiously named Pig Stomach Mushrooms (猪肚菇 zhū dù gū, Infundibulicybe gibba. These are another favourite. They make a lovely mushroom omelette. Also, a summer find. And finally, not a mushroom, but certainly a fungus and available fresh is the wood ear (木耳 mù ěr), Auricularia heimuer. It tastes of almost nothing, but is prized in Chinese cuisine for its crunchy texture. More usually sold dried, it is available fresh in the supermarkets now. Please note that where I have given Chinese names, these are the names most commonly used around this part of China, but many variations do exist. Coming up next - the dried varieties available.

-

While there have been other Chinese vegetable topics in the past, few of them were illustrated and some which were have lost those images in various "upgrades", or because they were hosted elsewhere on now defunct sites.. What I plan to do is photograph every vegetable I see and say what it is, if I know. However, this is a formidable task so it'll take time. The problem is that so many vegetables go under many different Chinese names and English names adopted from one or other Chinese language, too. For example, I know four different words for 'potato' and know there are more. And there are multiple regional preference in nomenclature. Most of what you will see will be vegetables from supermarkets, where I can see the Chinese labelling. In "farmer's" or wet markets, there is no labelling and although, If I ask, different traders will have different names for the same vegetable. Many a time I've been supplied a name, but been unable to find any reference to it from Mr Google or his Chinese counterparts. Or if I find the Chinese, can't find an accepted translation so have to translate literally. Also, there is the problem that most of the names which are used in the English speaking countries have, for historical reasons, been adopted from Cantonese, whereas 90% of Chinese speak Mandarin (普通话 pǔ tōng huà). But I will do my best to supply as many alternative names as I can find. I shall also attempt to give Chinese names in simplified Chinese characters as used throughout mainland China and then in traditional Chinese characters, now mainly only used in Hong Kong, Taiwan and among much of the Chinese diaspora. If I only give one version, that means they are the same in Simp and Trad. I'll try to do at least one a day. Until I collapse under the weight of vegetation. Please, if you know any other names for any of these, chip in. Also, please point out any errors of mine. I'll start with bok choy/choy. This is and alternatives such as pak choi or pok choi are Anglicised attempts at the Cantonese pronunciation of the Mandarin! However in Cantonese it is more often 紹菜; Jyutping: siu6 coi3. In Chinese it is 白菜. Mandarin Pinyin 'bái cài'. This literally means 'white vegetable' but really just means 'cabbage' and of course there are many forms of cabbage. Merely asking for bái cài in many a Chinese store or restaurant will be met with blank stares and requests to clarify. From here on I'm just going to translate 白菜 as 'cabbage'. So, here we go. Brassica rapa subsp. pekinensis This is what you may be served if you just ask for baicai. Or maybe not. In much of China it is 大白菜 dà bái cài meaning 'big cabbage'. In English, usually known as Napa or Nappa cabbage from the Japanese word, 菜っ葉, officially transliterated nabba, in English, Chinese cabbage, celery cabbage, Chinese leaf, etc. In Chinese, alternative names include 结球白菜 / 結球白菜 ( jié qiú bái cài ), literally knotted ball cabbage, but there are many more. This cabbage is also frequently pickled and becomes known as 酸菜 (Mand: suān cài; Cant: syun1 coi3) meaning 'sour vegetable', although this term is also used to refer to pickled mustard greens. Pickled cabbage. In 2016, a purple variety of napa cabbage was bred in Korea and that has been introduced to China as 紫罗兰白菜 (zǐ luó lán bái cài) - literally 'violet cabbage'. Purple Napa (Boy Choy)

-

Sea fish in my local supermarket In the past I've started a few topics focusing on categorised food types I find in China. I’ve done Mushrooms and Fungi in China Chinese Vegetables Illustrated Sugar in China Chinese Herbs and Spices Chinese Pickles and Preserves Chinese Hams. I’ve enjoyed doing them as I learn a lot and I hope that some people find them useful or just interesting. One I’ve always resisted doing is Fish etc in China. Although it’s interesting and I love fish, it just felt too complicated. A lot of the fish and other marine animals I see here, I can’t identify, even if I know the local name. The same species may have different names in different supermarkets or wet markets. And, as everywhere, a lot of fish is simply mislabelled, either out of ignorance or plain fraud. However, I’ve decided to give it a go. I read that 60% of fish consumed in China is freshwater fish. I doubt that figure refers to fresh fish though. In most of China only freshwater fish is available. Seawater fish doesn’t travel very far inland. It is becoming more available as infrastructure improves, but it’s still low. Dried seawater fish is used, but only in small quantities as is frozen food in general. I live near enough the sea to get fresh sea fish, but 20 years ago when I lived in Hunan I never saw it. Having been brought up yards from the sea, I sorely missed it. I’ll start with the freshwater fish. Today, much of this is farmed, but traditionally came from lakes and rivers, as much still does. Most villages in the rural parts have their village fish pond. By far the most popular fish are the various members of the carp family with 草鱼 (cǎo yú) - Ctenopharyngodon idella - Grass Carp being the most raised and consumed. These (and the other freshwater fish) are normally sold live and every supermarket, market (and often restaurants) has ranks of tanks holding them. Supermarket Freshwater Fish Tanks You point at the one you want and the server nets it out. In markets, super or not, you can either take it away still wriggling or, if you are squeamish, the server will kill, descale and gut it for you. In restaurants, the staff often display the live fish to the table before cooking it. These are either steamed with aromatics – garlic, ginger, scallions and coriander leaf / cilantro being common – or braised in a spicy sauce or, less often, a sweet and sour sauce or they are simply fried. It largely depends on the region. Note that, in China, nearly all fish is served head on and on-the-bone. 草鱼 (cǎo yú) - Ctenopharyngodon idella - grass carp More tomorrow.

-

It sometimes seems likes every town in China has its own special take on noodles. Here in Liuzhou, Guangxi the local dish is Luosifen (螺蛳粉 luó sī fěn). It is a dish of rice noodles served in a very spicy stock made from the local river snails and pig bones which are stewed for hours with black cardamom, fennel seed, dried tangerine peel, cassia bark, cloves, pepper, bay leaf, licorice root, sand ginger, and star anise. Various pickled vegetables (but especially pickled bamboo shoots), dried tofu skin, fresh green vegetables, peanuts and loads of chilli are then usually added. Few restaurants ever reveal their precise recipe, so this is tentative. Luosifen is only really eaten in small restaurants and roadside stalls. I've never heard of anyone making it at home. In order to promote tourism to the city, the local government organised a food festival featuring an event named "10,000 people eat luosifen together." (In Chinese 10,000 often just means "many".) 10,000 people (or a lot of people anyway) gathered at Liuzhou International Convention and Exhibition Centre for the grand Liuzhou luosifen eat-in. Well, they gathered in front of the centre – the actual centre is a bleak, unfinished, deserted shell of a building. I disguised myself as a noodle and joined them. 10,001. The vast majority of the 10,000 were students from the local colleges who patiently and happily lined up to be seated. Hey, mix students and free food – of course they are happy. Each table was equipped with a basket containing bottled water, a thermos flask of hot water, paper bowls, tissues etc. And most importantly, a bunch of Luosifen caps. These read “万人同品螺蛳粉” which means “10,000 people together enjoy luosifen” Yep, that is the soup pot! 15 meters in diameter and holding eleven tons of stock. Full of snails and pork bones, spices etc. Chefs delicately added ingredients to achieve the precise, subtle taste required. Noodles were distributed, soup added and dried ingredients incorporated then there was the sound of 10,000 people slurping. Surrounding the luosifen eating area were several stalls selling different goodies. Lamb kebabs (羊肉串) seemed most popular, but there was all sorts of food. Here are few of the delights on offer. Whole roast lamb or roast chicken Lamb Kebabs Kebab spice mix – Cumin, chilli powder, salt and MSG Kebab stall Crab Different crab Sweet sticky rice balls Things on sticks Grilled scorpions Pig bones and bits Snails And much more. To be honest, it wasn’t the best luosifen I’ve ever eaten, but it was wasn’t the worst. Especially when you consider the number they were catering for. But it was a lot of fun. Which was the point.

-

I would like to start this thread to post some guides to buying ingredients to cooking Chinese food, such as sauces, fresh produce and dried goods. This is for the benefits of those who are not familiar with Chinese cooking ingredients. Each page will have a picture accompanying with the description of the item, and some tips on where to find them and what to look for, and (if any) my favorite brand. Feel free to add comments. At some point, I will create an index page for easy references. Over time, we will have a comprehensive list.

-

Hello! I have taken quite a few trips to China and have done my best to take cooking classes, and capture new recipes while I've been there. My favorite foods are the street foods, and with the exception of Fuchsia Dunlop's amazing books, it has been very hard to find recipes for the "real deal". The memorable foods I've had in my travels were in Xi'an, in the Muslim district where they have stall after stall of amazing street food. My favorite food was Guo Kui, which was a flaky fried dough (almost pastry-like), stuffed with minced meat, sichuan pepper and chilies. It was incredible and I cant find anything online to tell me how it's made. I'm wondering if anyone out there has a recipe they can share? Fuchsia Dunlop describes this food in her newest book, Shark's Fin and Sichuan Pepper, but unfortunately there is no recipe and I've found no way to contact the author. Any assistance is much appreciated! Thanks Marc

-

Having cooked meals and ingredients etc delivered to your office or home is hugely popular here in China. The biggest supplier is Meituan and you see dozens of their electric scooters dashing around every day. There isn't much you can't buy (anything from a raw egg to flock of live ostriches) and delivery is usually within 30 minutes. I have eaten from this source before but today was my first time to order for myself. This issue is due to my being confined to bed in a hospital with a more than usually dysfunctional kitchen. Anyway, here is my introductory dish. Spicy cumin beef fried rice with a vegetable soup from heaven The broth was indescribable. These dishes are from Lanzhou in NW China. Those who know the China Food Myths topic will note the lack of egg in the fried rice Cost me 26 cents US / 22 pence UK. This includes a huge welcome discount. The regular price is about 12 times that.

-

This arose from this topic, where initially @Anna N asked about tea not being served at the celebratory meal I attended. I answered that it is uncommon for tea to be served with meals (with one major exception). I was then asked for further elucidation by @Smithy. I did start replying on the topic but the answer got longer than I anticipated and was getting away from the originally intended topic about one specific meal. So here were are.. I'd say there are four components to tea drinking in China. a) When you arrive at a restaurant, you are often given a pot of tea which people will sip while contemplating the menu and waiting for other guests to arrive. Dining out is very much a group activity, in the main. When everyone is there and the food dishes start to arrive the tea is nearly always forgotten about. The tea served like this will often be a fairly cheap, common brand - usually green. You also may be given a cup of tea in a shop if your purchase is a complicated one. I recently bought a new lap top and the shop assistant handed me tea to sip as she took down the details of my requirements. Also, I recently had my eyes re-tested in order to get new spectacles. Again, a cup of tea was provided. Visit someone in an office or have a formal meeting and tea or water will be provided. b) You see people walking about with large flasks (not necessarily vacuum flasks) of tea which they sip during the day to rehydrate themselves. Taxi drivers, bus drivers, shop keepers etc all have their tea flask. Of course, the tea goes cold. I have a vacuum flask, but seldom use it - not a big tea fan. There are shops just dedicated to selling the drinks flasks. c) There has been a recent fashion for milk tea and bubble tea here, two trends imported from Hong Kong and Taiwan respectively. It is sold from kiosks and mainly attracts younger customers. McDonald's and KFC both do milk and bubble teas. Bubble and Milk Tea Stall And Another And another - there are hundreds of them around! McDonald's Ice Cream and Drinks Kiosk. McDonald's Milk Tea Ad d) There are very formal tea tastings and tea ceremonies, similar in many ways to western wine tastings. These usually take place in tea houses where you can sample teas and purchase the tea for home use. These places can be expensive and some rare teas attract staggering prices. The places doing this pride themselves on preparing the tea perfectly and have their special rituals. I've been a few times, usually with friends, but it's not really my thing. Below is one of the oldest serious tea houses in the city. As you can see, they don't go out of their way to attract custom. Their name implies they are an educational service as much as anything else. Very expensive! Tea House Supermarkets and corner shops carry very little tea. This is the entire tea shelving in my local supermarket. Mostly locally grown green tea. Local Guangxi Tea The most expensive in the supermarket was this Pu-er Tea (普洱茶 pǔ ěr chá) from Yunnan province. It works out at ¥0.32per gram as opposed to ¥0.08 for the local stuff. However, in the tea houses, prices can go much, much higher!

- 31 replies

-

- 10

-

-

-

China manufactures by far the majority of the world’s microwaves, but while it is true that many people in mainland China have them, very few are actually used for cooking. They are mostly seen as tools to reheat the last meal’s leftovers. Of all those microwaves, those capable of baking (convection microwaves) are a small percentage and three to five times more expensive. Even those who do own such things seldom bake in them and they can’t bake everything. There was a brief fashion about eight years ago for baking, but most people were using toaster ovens to bake Western style cakes. Nothing Chinese. Several shops opened selling the appropriate ingredients. 90% of them lasted a year or two at most. People moved on the next craze. The bookshops had a few Western style bakery cookbooks, but no longer.

-

Chinese food must be among the most famous in the world. Yet, at the same time, the most misunderstood. I feel sure (hope) that most people here know that American-Chinese cuisine, British-Chinese cuisine, Indian-Chinese cuisine etc are, in huge ways, very different from Chinese-Chinese cuisine and each other. That's not what I want to discuss. Yet, every day I still come across utter nonsense on YouTube videos and Facebook about the "real" Chinese cuisine, even from ethnically Chinese people (who have often never been in China). Sorry YouTube "influencers", but sprinkling soy sauce or 5-spice powder on your cornflakes does not make them Chinese! So what is the "authentic" Chinese food? Well, like any question about China, there are several answers. It is not surprising that a country larger than western Europe should have more than one typical culinary style. Then, we must distinguish between what you may be served in a large hotel dining room, a small local restaurant, a street market stall or in a Chinese family's home. That said, in this topic, I want to attempt to debunk some of the more prevalent myths. Not trying to start World War III. But don't get me started on Crab Frigging Rangoon! When I moved to China from the UK 25 years ago, I had my preconceptions. They were all wrong. Sweet and sour pork with egg fried rice was reported to be the second favourite dish in Britain, and had, of course, to be preceded by a plate of prawn/shrimp crackers. All washed down with a lager or three. Yet, in that quarter of a century, I've seldom seen a prawn cracker; they are Indonesian, not Chinese. And egg fried rice is usually eaten as a quick dish on its own, not usually as an accompaniment to main courses. Every menu featured a starter of prawn/shrimp toast which I have never seen in mainland China - just once in Hong Kong. But first, one myth needs to be dispelled. The starving Chinese! When I was a child I was encouraged to eat the particularly nasty bits on the plate by being told that the starving Chinese would lap them up. My suggestion that we could post it to them never went down too well. At that time (the late fifties) there was indeed a terrible famine in China (almost entirely manmade (Maomade)). When I first arrived in China, it was after having lived in Soviet Russia and I expected to see the same long lines of people queuing up to buy nothing very much in particular. Instead, on my first visit to a market (in Hunan Province), I was confronted with a wider range of vegetables, seafood, meat and assorted unidentified frying objects than I have ever seen anywhere else. And it was so cheap I couldn't convert to UK pounds or any other useful currency. I'm going to start with some of the simpler issues - later it may get ugly! 1. Chinese people eat everything with chopsticks. No, they don't! Most things, yes, but spoons are also commonly used in informal situations. I recently had lunch in a university canteen. It has various stations selling different items. I found myself by the fried rice stall and ordered some Yangzhou fried rice. Nearly all the students and faculty sitting near me were having the same. I was using my chopsticks to shovel the food in, when I noticed that I was the only one doing so. Everyone else was using spoons. On investigating, I was told that the lunch break is so short at only two-and-a-half hours that everyone wants to eat quickly and rush off for their compulsory siesta. I've also seen claims that people eat soup with chopsticks. Nonsense. While people use chopsticks to pick out choice morsels from the broth, they will drink the soup by lifting their bowl to their mouths like cups. They ain't dumb! Anyway, with that very mild beginning, I'll head off and think which on my long list will be next. Thanks to @KennethT for advice re American-Chinese food.

-

I recently purchased a bottle of Lee Kum Kee premium oyster sauce, which has been my go-to choice for quite some time. However, I hadn't purchased it for a couple-three years. When I used it last night I was somewhat disappointed - it didn't taste the way I remembered it. Could be the sauce has changed, or, more likely, my palate has changed. In any case, I'd like to experiment with some different options. What suggestions do the oyster sauce sophisticates have to offer? Maybe something not as salty, or less filled with additives and coloring? I've heard that some Thai oyster sauces are an improvement over LKK. Any suggestions in that regard?

-

Hello everyone, This is my first post, so please tell me if I've made any mistakes. I'd like to learn the ropes as soon as possible. I first learned of this cookbook from The Mala Market, easily the best online source of high-quality Chinese ingredients in the west. In the About Us page, Taylor Holiday (the founder of Mala Market) talks about the cookbooks that inspired her. This piqued my interest and sent me down a long rabbit hole. I'm attempting to categorically share everything I've found about this book so far. Reading it online Early in my search, I found an online preview (Adobe Flash required). It shows you the first 29 pages. I've found people reference an online version you can pay for on the Chinese side of the internet. But to my skills, it's been unattainable. The Title Because this book was never sold in the west, the cover, and thus title, were never translated to English. Because of this, when you search for this book, it'll have several different names. These are just some versions I've found online - typos included. Sichuan (China) Cuisine in Both Chinese and English Si Chuan(China) Cuisinein (In English & Chinese) China Sichuan Cuisine (in Chinese and English) Chengdu China: Si Chuan Ke Xue Ji Shu Chu Ban She Si Chuan(China) Cuisinein (Chinese and English bilingual) 中国川菜:中英文标准对照版 For the sake of convenience, I'll be referring to the cookbook as Sichuan Cuisine from now on. Versions There are two versions of Sichuan Cuisine. The first came out in 2010 and the second in 2014. In an interview from Flavor & Fortune, a (now defunct) Chinese cooking magazine, the author clarifies the differences. That is all of the information I could find on the differences. Nothing besides that offhanded remark. The 2014 edition seems to be harder to source and, when available, more expensive. Author(s) In the last section, I mentioned an interview with the author. That was somewhat incorrect. There are two authors! Lu Yi (卢一) President of Sichuan Tourism College, Vice Chairman of Sichuan Nutrition Society, Chairman of Sichuan Food Fermentation Society, Chairman of Sichuan Leisure Sports Management Society Du Li (杜莉) Master of Arts, Professor of Sichuan Institute of Tourism, Director of Sichuan Cultural Development Research Center, Sichuan Humanities and Social Sciences Key Research Base, Sichuan Provincial Department of Education, and member of the International Food Culture Research Association of the World Chinese Culinary Federation Along with the principal authors, two famous chefs checked the English translations. Fuchsia Dunlop - of Land of Plenty fame Professor Shirley Cheng - of Hyde Park New York's Culinary Institute of America Fuchsia Dunlop was actually the first (and to my knowledge, only) Western graduate from the school that produced the book. Recipes Here are screenshots of the table of contents. It has some recipes I'm a big fan of. ISBN ISBN 10: 7536469640 ISBN 13: 9787536469648 As far as I can tell, the first and second edition have the same ISBN #'s. I'm no librarian, so if anyone knows more about how ISBN #'s relate to re-releases and editions, feel free to chime in. Publisher Sichuan Science and Technology Press 四川科学技术出版社 Cover Okay... so this book has a lot of covers. The common cover A red cover A white cover A white version of the common cover An ornate and shiny cover There may or may not be a "Box set." At first, I thought this was a difference in book editions, but that doesn't seem to be the case. As far as covers go, I'm at a loss. If anybody has more info, I'm all ears. Buying the book Alright, so I've hunted down many sites that used to sell it and a few who still have it in stock. Most of them are priced exorbitantly. AbeBooks.com ($160 + $15 shipping) Ebay.com - used ($140 + $4 shipping) PurpleCulture.net ($50 + $22 shipping) Amazon.com ($300 + $5 shipping + $19 tax) A few other sites in Chinese I bought a copy off of PurpleCuture.net on April 14th. When I purchased Sichuan Cuisine, it said there was only one copy left. That seems to be a lie to create false urgency for the buyer. My order never updated past processing, but after emailing them, I was given a tracking code. It has since landed in America and is in customs. I'll try to update this thread when (if) it is delivered. Closing thoughts This book is probably not worth all the effort that I've put into finding it. But what is worth effort, is preserving knowledge. It turns my gut to think that this book will never be accessible to chefs that have a passion for learning real Sichuan food. As we get inundated with awful recipes from Simple and quick blogs, it becomes vital to keep these authentic sources available. As the internet chugs along, more and more recipes like these will be lost. You'd expect the internet to keep information alive, but in many ways, it does the opposite. In societies search for quick and easy recipes, a type of evolutionary pressure is forming. It's a pressure that mutates recipes to simpler and simpler versions of themselves. They warp and change under consumer pressure till they're a bastardized copy of the original that anyone can cook in 15 minutes. The worse part is that these new, worse recipes wear the same name as the original recipe. Before long, it becomes harder to find the original recipe than the new one. In this sense, the internet hides information.

-

A Gremolata reader is looking for Chinese Mustard (either powdered or already mixed). I have not been able to reconnoitre any of the China towns, and am lazily posting in the hope that that there's a TO eGulleter that knows where to find...

-

I am looking for a recipe for custard buns, those white steamed buns with bright yellow egg custard in the middle. I haven't seen any recipes for this anywhere, not even Wei Chuan. Can anyone help? Also, what kind of flour do you use for your bao recipes? I like my bao dough to turn out unnaturally white and very fluffy just like at Koi Palace in San Francisco. But I think it's my flour or something that is not letting do that. Help! Also, does anyone know of a really good recipe for shanghai "juicy" dumplings? Soup dumplings? custard tarts? Thanks in advance.

-

I’m an idiot. It’s official. A couple of weeks back, on another thread, the subject of celtuce and its leafing tops came up (somewhat off-topic). Someone said that the tops are difficult to find in Asian markets and I replied that I also find the tops difficult to find here in China. Nonsense. They are very easy to find. They just go under a completely different name from the stems – something which had slipped my very slippery mind. So, here on-topic is some celtuce space. First, for those who don’t know what celtuce is, let me say it is a variety of lettuce which looks nothing like a lettuce. It is very popular in southern mainland China and Taiwan. It is also known in English as stem lettuce, celery lettuce, asparagus lettuce, or Chinese lettuce. In Chinese it is 莴笋 wō sǔn or 莴苣 wō jù, although the latter can simply mean lettuce of any variety. Lactuca sativa var. asparagina is 'celtuce' for the technically minded. Those in the picture are about 40 cm (15.7 inches) long and have a maximum diameter of 5 cm (2 inches). The stems are usually peeled, sliced and used in various stir fries, although they can also be braised, roasted etc. The taste is somewhere between lettuce and celery, hence the name. The texture is more like the latter. The leafing tops are, as I said, sold separately and under a completely different name. They are 油麦菜 yóu mài cài. These taste similar to Romaine lettuce and can be eaten raw in salads. In Chinese cuisine, they are usually briefly stir fried with garlic until they wilt and served as a green vegetable – sometimes with oyster sauce. If you can find either the stems or leaves in your Asian market, I strongly recommend giving them a try.

-

I've mentioned the craze for Luosifen which led to 6 million sheep following each other to Liuzhou over the CNY holiday to try a dish half of them hoped to hate. But it's not the only insane craze. Back in summer 1998, when I was living in Hunan, there was catastrophic flooding which wiped out the soy bean harvest. Thousands of farmers were hit by disaster. A couple of the more enterprising kind started making a kind of snack product using wheat flour rather than the hard-hit soya flour normally used in their cuisine. Basically they made wheat gluten strips which they slavered in chilli. These they called S: 辣条; T: 辣條 (là tiáo), 'spicy strips' and sold them outside schools for mere cents. Latiao - image from Meituan food delivery app. A billion dollar industry was born. Most of the customers were and still are schoolchildren who went crazy for the addictive if not nutritious snacks. According to an article in Global Times, China's uber-nationalist State-owned English language 'newspaper', latiao has gone viral globally. I don't believe a word of it. In China, yes. Globally? Have you or your children, grand-children, great-grand-children even heard, never mind fallen for this? For the record, I've never eaten them. A non-hysterical history of the craze is here. https://www.theworldofchinese.com/2024/02/stripped-down-the-story-behind-chinas-favorite-snack/

-

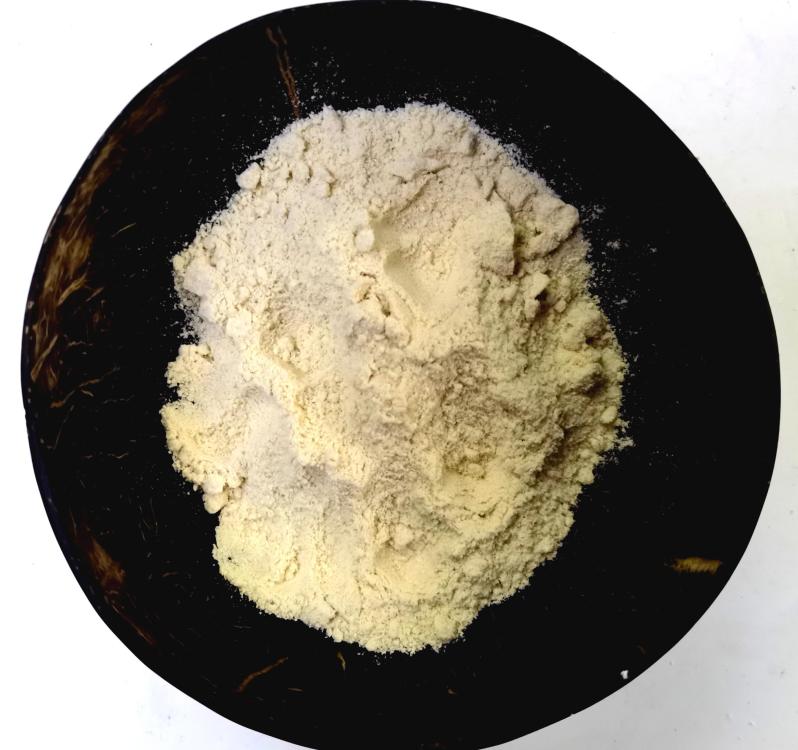

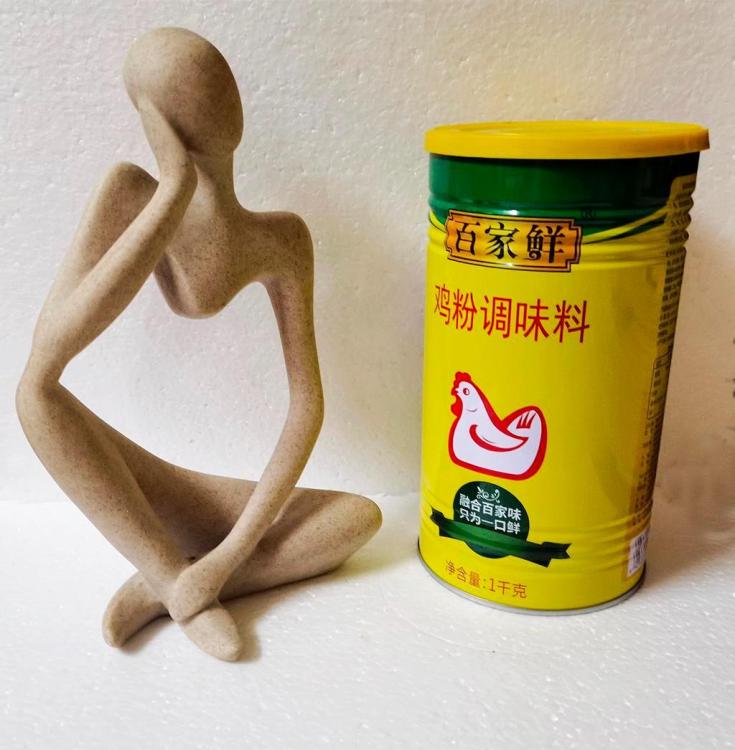

A side discussion on the Dinner 2024 topic promoted this. Chinese cooks, from the most elevated chefs to the home cook and all the way down to this crazy foreigner in their midst, swear by 鸡粉 (jī fěn), chicken powder. It is used to enhance or even make stocks or braising liquids; it is sprinkled on stir fries and other dishes like any other seasoning; it is added to drinks. I've even seen it added to cocktails. Anywhere umami is wanted. Knorr and other western brands can be found in China but are not particularly popular. Lee Kum Kee was mentioned but I've never seen that particular LKK product in China. KKK products, which I have never rated, are more popular abroad. So, I thought it may be useful to mention the most popular brands here, some of which are likely to be available in Asian markets. Before doing so, I will say that most Chinese brands unashamedly contain MSG. I have no intention of resurrecting that horse which is not only dead but has been utterly cremated, mourned, disinterred and reburied several times before. Nothing wrong with MSG. So, some brands. 厨邦 (chú bāng) means 'kitchen nation'. It is medium level brand with less of a pronounced flavour as some of the others below. Certainly not first choice. 大桥 (dà qiáo) means 'great bridge' and while their powder is fine I wouldn't extend that to 'great' among the following. 太太乐 (tài tai lè) Mrs Le. Mrs Happy is a popular brand which I happily put in second place. Umami rich with a good chicken flavor. 百家鲜 (bǎi jiā xiǎn) literally means '100 households' choice', but 百 also just means 'all kinds of'. All kinds of households' choice. It is certainly the biggest seller. It smells and tastes like roast chicken straight from the oven. I'd bet of the 96 apartments in my block, 90% have a pack in the kitchen. I buy it in 1kg tubs and am never without it. Restaurants buy it by the sack load.

-

Chef Wang is one of my favorite YouTube channels, and a few weeks ago he got into trouble with the system. HERE is the CNN version of the story. HERE'S a slightly biased video explaining the cultural implications a bit more. My 5 second summary: A long-forgotten Chinese general was hiding in the mountains during a war, and decided to cook egg fried rice, which sent off smoke plumes that alerted the enemy of his whereabouts. Stupid mistake. So, if you cook egg fried rice near the end of September, when this incident happened, you are considered unpatriotic. Chef Wang released an egg fried rice video a few weeks ago, which is now gone from his play list. I saw the video and thought it was an odd step backwards in his repertoire, but he does do quite a bit of home cooking on top of his restaurant quality dishes. Was it on purpose? Who knows, but he apologized and said he would never release an egg fried rice video again. He hasn't posted any videos since. FWIW, he lightly argued that he releases numerous fried rice videos throughout the year, so this was just poorly timed. Well, I hope he's able to come back because quite frankly his channel was a wonderful gateway to Chinese culture, and the far vast majority of the world would have had no idea of the backstory had the Chinese government not alerted us to the gaff.

-

Do a loose search for ‘Chinese Cuisine’ and often you’ll be directed to books or websites telling you that China has eight distinct cuisines. Unfortunately, this is yet another myth. The repetition of this ‘fact’ comes from the Imperial court stating such hundreds of years ago and it becoming a cliché, both in and out of China. The eight are usually listed as: 鲁菜 (lǔ cài), Shandong cuisine 粤菜 (yuè cài) Cantonese cuisine 川菜 (chuān cài) Sichuan cuisine 苏菜 (sū cài) Jiangsu cuisine 湘菜 (xiāng cài) Hunan cuisine 浙菜 (zhè cài) Zhejiang cuisine 徽菜 (huī cài) Anhui cuisine 闽菜 (mǐn cài) Fujian cuisine The list was compiled when China’s present day borders were somewhat different. In fact, not only are there many, many more; even within these categories there are distinctly different cuisines. Hunan, for example has three distinguishably different cuisines, as does Guangxi where I live. Also, the list excludes many more. It only includes the majority Han Chinese cuisines and excludes the ethnic minority cuisines of which there are so many. It also excludes significant cuisines such as Yunnan cuisine, Guizhou cuisine, Shaanxi cuisine, Xinjiang cuisine, Dongbei cuisine, Inner Mongolian cuisine, Tibetan cuisine and more. It doesn’t even include Beijing or Shanghai, both of which have their own distinct cuisines. Over the next few posts I will attempt to herd cats and describe some of the eight, but more of the others as they tend to be less well known out of China.

-

Hi everyone, Please don't think I'm an idiot, but I have a question about dumplings. Also, if I am posting in the wrong place, redirection is welcome! I am making dumplings with shredded cabbage, tree ear/black Chinese/button mushrooms, and leeks for a party this weekend. I wonder if I can do them in advance, and if so, how far in advance? I am using purchased wrappers and I am afraid they will stick or get v. soggy if I let them sit for too long. Also, what mushroom combos are good? My Midwestern grocery store ACTUALLY has some things besides regular mushrooms for once, and, there was an Asian grocery opened a few weeks ago I have not tried too many combos but I love, love mushrooms. Any advice? Thank you very much!

-

I am stopping over in Singapore for unfortunately only one night and have been reading up on the food, particularly hawker centres, and how to order it. I'm sure I would be able to get by with English and pointing but I find their crossroads culture fascinating and I always like to learn a tiny bit of the language wherever I go. So it is part practical, part cultural. I realize that I am not getting pronunciation from internet sources but I have started to compile information, that may be interesting to others here, in a text file. What other food-related language in Singapore do you know? Obviously much originated with Chinese, Malay, and other cultures and I would be interested in similarities/differences in the language. Rather than a total dump, here is what I have thus far on coffee and tea. Even more complicated than ordering coffee in Australia or at Starbucks! Kopi (coffee with condensed milk & sugar) Teh (tea with condensed milk & sugar) Kopi o (coffee with no condensed milk, still has sugar) Teh o (tea with no condensed milk, still has sugar) Kopi o kosong (coffee with no condensed milk & no sugar) Teh o kosong (tea with no condensed milk & no sugar) Teh c (tea with evaporated milk & sugar) Tak giu (Milo) Diao yu (tea bag in hot water) Ditlo - no water added to your coffee or tea Kosong (no sugar, usually for beverages) Siew dai - less sweet Siew siew dai - less than siew dai (Malay stall usually go with ‘kurang manis’ than ‘siew dai’) Peng (Bing) (beverage with ice, Eg. kopi peng, teh peng) Teh tarik: Pulled tea. It is the national drink of Malaysia (Indian origin)

-

The highest quality Chinese-made cleavers that I have been able to find here in the U.S. are made by Chan Chi Kee of Hong Kong. Are there any other kitchen knives made in China at this quality level or higher?

-

Hi, Any suggestions for a fabulous Chinese meal? I’m looking for a restaurant that not only does fantastic food, but where the service is also of high standard ( I know this is normally not the norm with Chinese restaurants, that’s why I need your help!!) I’m planning a dinner out for next Friday (6 of us celebrating a birthday) Thank you

-

I wandered in awe through San Francisco's China Town recently. So big, so much variety! The produce was so fresh, and then it occured to me that much of the produce I buy on the East Coast comes from California. Among the things that baffled me, and I didn't ask because if I bought any I had no place to take it, was something that looked like slab bacon and probably was pig belly hanging like those ducks and chickens. And while we're at it, what's with the ducks and chickens? I have this fear unrefrigerated poultry, but these have obviously been cooked to a preserved state. I have a gut feeling they're delicious.

-

Big Plate Chicken - 大盘鸡 (dà pán jī) This very filling dish of chicken and potato stew is from Xinjiang province in China's far west, although it is said to have been invented by a visitor from Sichuan. In recent years, it has become popular in cities across China, where it is made using a whole chicken which is chopped, with skin and on the bone, into small pieces suitable for easy chopstick handling. If you want to go that way, any Asian market should be able to chop the bird for you. Otherwise you may use boneless chicken thighs instead. Ingredients Chicken chopped on the bone or Boneless skinless chicken thighs 6 Light soy sauce Dark soy sauce Shaoxing wine Cornstarch or similar. I use potato starch. Vegetable oil (not olive oil) Star anise, 4 Cinnamon, 1 stick Bay leaves, 5 or 6 Fresh ginger, 6 coin sized slices Garlic. 5 cloves, roughly chopped Sichuan peppercorns, 1 tablespoon Whole dried red chillies, 6 -10 (optional). If you can source the Sichuan chiles known as Facing Heaven Chiles, so much the better. Potatoes 2 or 3 medium sized. peeled and cut into bite-sized pieces Carrot. 1, thinly sliced Dried wheat noodles. 8 oz. Traditionally, these would be a long, flat thick variety. I've use Italian tagliatelle successfully. Red bell pepper. 1 cut into chunks Green bell pepper, 1 cut into chunks Salt Scallion, 2 sliced. Method First, cut the chicken into bite sized pieces and marinate in 1½ teaspoons light soy sauce, 3 teaspoons of Shaoxing and 1½ teaspoons of cornstarch. Set aside for about twenty minutes while you prepare the rest of the ingredients. Heat the wok and add three tablespoons cooking oil. Add the ginger, garlic, star anise, cinnamon stick, bay leaves, Sichuan peppercorns and chilies. Fry on a low heat for a minute or so. If they look about to burn, splash a little water into your wok. This will lower the temperature slightly. Add the chicken and turn up the heat. Continue frying until the meat is nicely seared, then add the potatoes and carrots. Stir fry a minute more then add 2 teaspoons of the dark soy sauce, 2 tablespoons of the light soy sauce and 2 tablespoons of the Shaoxing wine along with 3 cups of water. Bring to a boil, then reduce to medium. Cover and cook for around 15-20 minutes until the potatoes are done. While the main dish is cooking, cook the noodles separately according to the packet instructions. Reserve some of the noodle cooking water and drain. When the chicken and potatoes are done, you may add a little of the noodle water if the dish appears on the dry side. It should be saucy, but not soupy. Add the bell peppers and cook for three to four minutes more. Add scallions. Check seasoning and add some salt if it needs it. It may not due to the soy sauce and, if in the USA, Shaoxing wine. Serve on a large plate for everyone to help themselves from. Plate the noodles first, then cover with the meat and potato. Enjoy.