-

Posts

16,768 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Profile Information

-

Location

Liuzhou, Guangxi, China

Recent Profile Visitors

89,642 profile views

-

Coincidentally, I came across this today. https://www.mirror.co.uk/lifestyle/food-drink/experts-say-storing-potatoes-one-36556687

-

Unfortunately, that often doesn't work. Many websites (especially media sites) detect and block VPNs.

-

-

-

- 109 replies

-

- 13

-

-

-

-

Mushroom powder is widely available in stores here from a large variety of species. I do make my own shiitake powder but I regularly buy this matsutake powder and use it as a seaoning pretty much like salt.

-

This ugly specimen is 斑鱼 (bān yú, blotched black fish), channa maculata. Native to China but introduced as an invasive species elsewhere. Mildly sweet and flaky, these are usually 20 to 30 cm (8 to 12 inches long.

-

After months of struggling, my Chinese burrito place has officially posted a notice stating they will permanently stop trading on February 6th, although they have already stopped delivery service. A nation (well me) is in mourning.

-

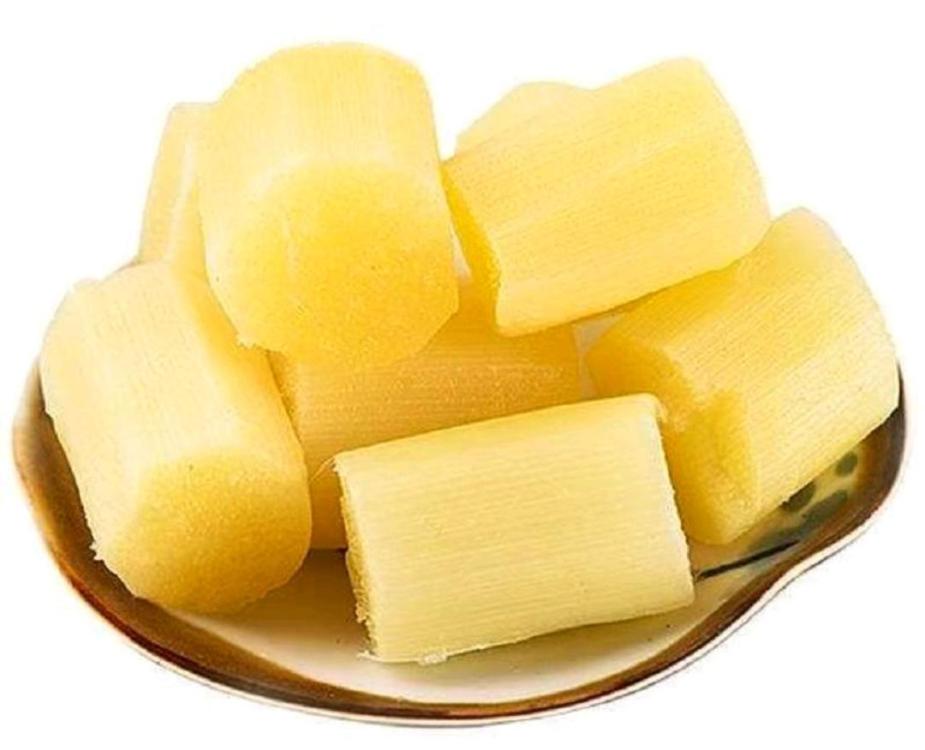

Not really fruit but always sold by the fruit people. Or street vendors. In the local dialect usually 甘蔗 (gān zhè), which, to my confusion on first hearing it, is pronounced almost exactly like 'ganga'. It is of course sugar cane. Fruity and very sweet.

-

By farr, my favourite way to cook green beans. https://food52.com/recipes/20767-fuchsia-dunlop-s-sichuanese-dry-fried-green-beans

-

The book is interesting but the title perhaps somewhat misleading. It's basically a recipe book of classic French cooking as cooked in a 2 Michelin star restaurant by French chef. Certainly not a guidebook for beginners as you have described yourself.

-

liuzhou changed their profile photo

-

To an extent it depends what sort of butter we're talking about. I only usually buy salted butter, which is difficult to find here, so I buy a few packs at a time and freeze them. The one in current use just goes into the fridge in its original packaging and lasts as long as it takes me to get through it. Certainly weeks. Living in the tropics, I'm careful not to leave it out any longer than necessary. Unsalted butter I'd be more careful with. Also with my annual treat of artisanal French butter imported at great expense !

-

A week in Komodo (Indonesia) - Take 1

liuzhou replied to a topic in Elsewhere in Asia/Pacific: Dining

@KennethT "non-cake bread is my little joke. Much of the bread in SE Asia has a texture that resembles cake. It's rare to find bread that has actual bread-like texture and crust." And in China, where it's also cake sweet. I keep telling them but they don't believe me.