On 8/17/2021 at 10:39 PM, Tropicalsenior said:Could you elaborate a bit on the difference between green and red Szechuan peppercorns? Have you done a topic on Chinese herbs and spices? Thank you.

Your wish is my command! Sometimes! A lot of what I say here, I will have already said in scattered topics across the forums, but I guess it's useful to bring it all into one place.

First, I want to say that China uses literally thousands of herbs. But not in their food. Most herbs are used medicinally in Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), often in their dried form. Some of the more common are sold in supermarkets, but more often in pharmacies or small specialist stores. I also often see people on the streets with baskets of unidentified greenery for sale - but not for dinner. The same applies to spices, although more spices are used in a culinary setting than are herbs.

I’ll start with Sichuan peppercorns as these are what prompted @Tropicalsenior to suggest the topic.

1. Sichuan Peppercorns

Sichuan peppercorns are neither pepper nor, thank the heavens, c@rn! Nor are they necessarily from Sichuan. They are actually the seed husks of one of a number of small trees in the genus Zanthoxylum and are related to the citrus family. The ‘Sichuan’ name in English comes from their copious use in Sichuan cuisine, but not necessarily where they are grown. Known in Chinese as 花椒 (huājiāo), literally ‘flower pepper’’, they are also known as ‘prickly ash’ and, less often, as ‘rattan pepper’.

The most common variety used in China is 红花椒 (hóng huā jiāo) or red Sichuan peppercorn, but often these are from provinces other than Sichuan, especially Gansu, Sichuan’s northern neighbour. They are sold all over China and, ground, are a key ingredient in “five-spice powder” mixes. They are essential in many Sichuan dishes where they contribute their numbing effect to Sichuan’s 麻辣 (má là), so-called ‘hot and numbing’ flavour. Actually the Chinese is ‘numbing and hot’. I’ve no idea why the order is reversed in translation, but it happens a lot – ‘hot and sour’ is actually ‘sour and hot’ in Chinese!

The peppercorns are essential in dishes such as 麻婆豆腐 (má pó dòu fǔ) mapo tofu, 宫保鸡丁 (gōng bǎo jī dīng) Kung-po chicken, etc. They are also used in other Chinese regional cuisines, such as Hunan and Guizhou cuisines.

Red Sichuan peppercorns can come from a number of Zanthoxylum varieties including Zanthoxylum simulans, Zanthoxylum bungeanum, Zanthoxylum schinifolium, etc.

Red Sichuan Peppercorns

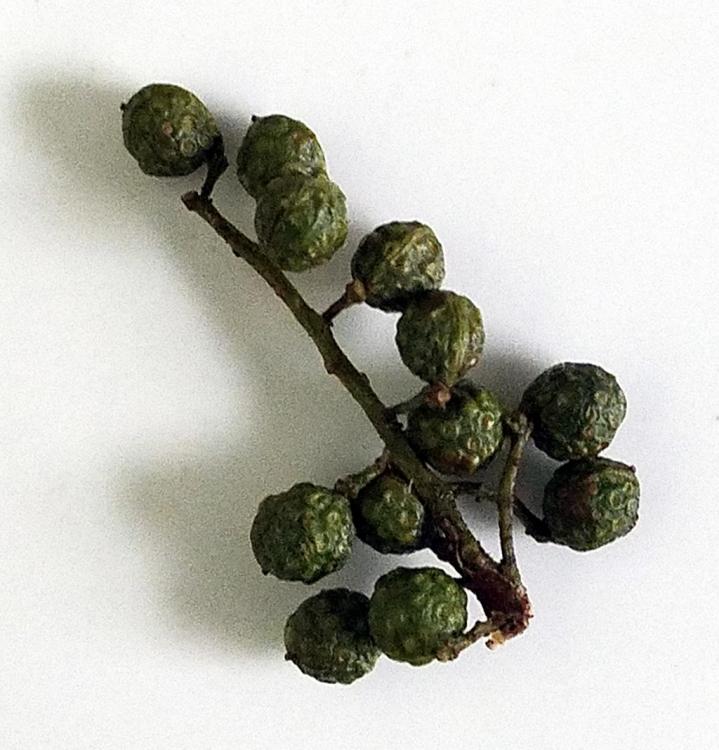

Another, less common, variety is 青花椒 (qīng huā jiāo) green Sichuan peppercorn, Zanthoxylum armatum. These are also known as 藤椒 (téng jiāo). This grows all over Asia, from Pakistan to Japan and down to the countries of SE Asia. This variety is significantly more floral in taste and, at its freshest, smells strongly of lime peel. These are often used with fish, rabbit, frog etc. Unlike red peppercorns (usually), the green variety are often used in their un-dried state, but not often outside Sichuan.

Green Sichuan Peppercorns

Fresh Green Sichuan Peppercorns

I strongly recommend NOT buying Sichuan peppercorns in supermarkets outside China. They lose their scent, flavour and numbing quality very rapidly. There are much better examples available on sale online. I have heard good things about The Mala Market in the USA, for example.

I buy mine in small 30 gram / 1oz bags from a high turnover vendor. And that might last me a week. It’s better for me to restock regularly than to use stale peppercorns.

Both red and green peppercorns are used in the preparation of flavouring oils, often labelled in English as 'Prickly Ash Oil'. 花椒油 (huā jiāo yóu) or 藤椒油 (téng jiāo yóu).

The tree's leaves are also used in some dishes in Sichuan, but I've never seen them out of the provinces where they grow.

A note on my use of ‘Sichuan’ rather than ‘Szechuan’.

If you ever find yourself in Sichuan, don’t refer to the place as ‘Szechuan’. No one will have any idea what you mean!

‘Szechuan’ is the almost prehistoric transliteration of 四川, using the long discredited Wade-Giles romanization system. Thomas Wade was a British diplomat who spoke fluent Mandarin and Cantonese. After retiring as a diplomat, he was elected to the post of professor of Chinese at Cambridge University, becoming the first to hold that post. He had, however, no training in theoretical linguistics. Herbert Giles was his replacement. He (also a diplomat rather than an academic) completed a romanization system begun by Wade. This became popular in the late 19th century, mainly, I suggest, because there was no other!

Unfortunately, both seem to have been a little hard of hearing. I wish I had a dollar for every time I’ve been asked why the Chinese changed the name of their capital from Peking to Beijing. In fact, the name didn’t change at all. It had always been pronounced with /b/ rather than /p/ and /ʤ/ rather than /k/. The only thing which changed was the writing system.

In 1958, China adopted Pinyin as the standard romanization, not to help dumb foreigners like me, but to help lower China’s historically high illiteracy rate. It worked very well indeed, Today, it is used in primary schools and in some shop or road signs etc., although street signs seldom, if ever, include the necessary tone markers without which it isn't very helpful.

A local shopping mall. The correct pinyin (with tone markers) is 'dōng dū bǎi huò'.

But pinyin's main use today is as the most popular input system for writing Chinese characters on computers and cell-phones. I use it in this way every day, as do most people. It is simpler and more accurate than older romanizations. I learned it in one afternoon. I doubt anyone could have done that with Wade-Giles.

Pinyin has been recognised for over 30 years as the official romanization by the International Standards Organization (ISO), the United Nations and, believe it or not, The United States of America, along with many others. Despite this recognition, old romanizations linger on, especially in America. Very few people in China know any other than pinyin. 四川 is 'sì chuān' in pinyin.