-

Posts

16,789 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Store

Help Articles

Everything posted by liuzhou

-

I'm confused too. I've never encountered a Brie or Camembert that was gratable, yet you say it's common. How old are these cheeses?

-

Hmmm. Pork belly is the most popular cut here.

-

A pictorial guide to Chinese cooking ingredients

liuzhou replied to a topic in China: Cooking & Baking

Not a great deal, but there is nothing the Chinese like more than gnawing on bones and sucking out the brains. It's the same thing as them loving to gnaw on chicken's or duck's feet (although they don't have brains!) Duck heads are popular, too. -

A pictorial guide to Chinese cooking ingredients

liuzhou replied to a topic in China: Cooking & Baking

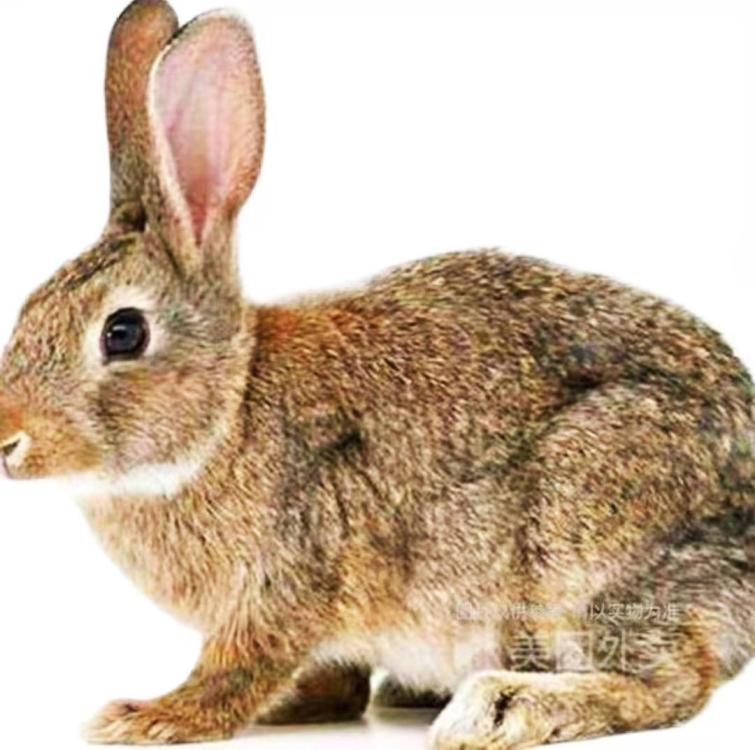

When I lived in London in the 1980s, the local supermarkets all stocked frozen 兔肉 (tù ròu), Oryctolagus cuniculus meat, imported from China. Since then the picture has changed somewhat. The rising population in China and the increased popularity of the meat means that China is now the world’s largest importer of the creatures. In 2025, China is expected to import over 100,000 metric tons of rabbit meat. 🐰 Rabbit is still exported in limited quantities but far outweighed by the amount of imports. The meat is widely available, but most popular in Sichuan province, where they have devised many recipes to highlight it. The most famous is probably the capital, Chengdu’s highly popular street food, 麻辣兔头 (má là tù tóu), braised rabbit head with mala ingredients (Sichuan peppercorns and chilli). Mala Rabbit Head Also popular dish is 冷吃兔丁 (lěng chī tù dīng), cold rabbit cubes. This simple sounding dish is anything but. Cubes of rabbit meat are fried in same mala ingredients. Cold Rabbit Cubes i also get these whole roasted rabbits from one supermarket. Rabbit with Leeks and Porcini Rabbit with Red Onion Jam and many more -

Here is personal favourite. 青头菌 (qīng tóu jūn), Green Headed Mushroom, Russula virescens. Despite the name, the colour varies from green to a light grey. They are also as the Green Cracking Russula or the Quilted Green Russula. The highly respected London Italian chef, grocer and wild mushroom expert, the late Antonio Carluccio described these as being "not exactly nice to look at". They can look a bit mouldy. Dried Green Headed Mushrooms They grow under tropical lowland rainforest trees in western Yunnan and we are just entering their season which will last until about September. Like shiitake and some other mushrooms, drying them enhances their flavour but cooking or even just soaking the dried mushrooms diminishes the colour. Some reports suggest that older specimens can smell like herrings, not something I’ve ever noticed. Rehydrated Dried Mushroom Care must be taken when foraging these, as younger specimens can resemble Amanita phalloides, the death cap mushroom, recently a feature in the Australian beef wellington murders case. They can be fried, grilled or even roasted. In taste, they are mild, nutty and fruity. They can also be eaten raw in salads, but the people of Yunnan don’t go there.

-

The difficult thing about doing these mushrooms is identifying what the hell they are. I only have the Chinese name for most. The Chinese rarely do scientific names and even when they do often get it wrong. One specimen was given a name that turned out to be a common houseplant; not anything fungal. Another led to a totally different mushroom. But mostly, I just don’t know. I can translate the Chinese name and search for that, but some names are rather cryptic, while others bear no relation to any real English name, so lead nowhere. This one is less opaque than most in that there is some information on it but I have still been unable to find any Latin name. It is 龙爪菇 (lóng zhuǎ gū) which translates as ‘Dragon’s Claw Mushroom’. It is native to Chinese but not specifically Yunnan. In fact, it was first found by commercial concerns in Fujian province, far from Yunnan. Most are foraged but they are successfully cultivated in very limited amounts in a few places. They rarely get exported. It is a type of clavarioid species, the coral fungi (in Chinese 珊瑚菇 (shān hú gū)) but that is an umbrella term covering many unrelated types. They must be cooked and the taste is mildly sweet and earthy. The texture is crispy and meaty.

-

... but for the non-entomophages among you, today's snackery. 油炸小鱼 (yóu zhá xiǎo yú), deep fried little fish. I bought these pre-cooked but add salt and chilli flakes.

-

Nothing wrong with scorpions! Taste just like crunchy shrimp. The venom in the tail is neutralised by cooking.

-

见手青 (jiàn shǒu qīng), Lanmaoa asiatica, are members of the Bolete family and native to south-west China. I am unaware of any reliable English name. No surprise; they rarely make it out of the Yunnan area. They are prized edibles but some people report mild hallucinatory experiences on eating them. Slightly more describe a mild high like being a bit happily tipsy. This lasts up to two hours. Scientists have so far been unable to identify which if any substance in the species is responsible. Most people report nothing at all but a nice dish of ‘shrooms. The mushrooms are noted for turning blue when bruised but that disappears when they are cooked. Usually sliced and often paired with bamboo shoots and fatty pork. The stems remain slightly crunchy and the caps meltingly soft. Even after the 30 minutes cook recommended by some Yunnan people to dispel any hallucinatory effects. I like. Who are these little green men dancing over there?

-

[Un]truth in Food Advertising: Marketing vs. Reality

liuzhou replied to a topic in Food Media & Arts

I posted this in another topic back in 2013 but it surely also belongs here. Courtesy of Sir Micky D's local branch. The promise: The reality I must point out for the record, m'lord that I didn't go to sample it - a colleague did and sent me the image. -

Some of the worst misrepresenting images of food advertising. The promise: Jianbing - Breakfast Pancakes What they served: No comment. I'm speechless.

- 40 replies

-

- 10

-

-

-

Most Yunnan mushrooms are wild and so foraged. They can be rather rare and seasonable and therefore on the pricy side but price also vary widely with the season and the harvest. One of the more common is 鸡纵菌 (jī zòng jūn), chicken mushrooms, umbrella mushrooms and sometimes termite mushrooms. The latter name is important , but somewhat misleading, in that there are many species called that. The Termitomyces family to which they all belong contains 52 types. The importance lies in that they grow in a symbiotic relationship with termites. In other words, they feed each other. They grow in Yunnan, but also in Guizhou and here in Guangxi on termite mounds in the mountain areas. It is said that there are seven varieties in Yunnan. I have access to these three. This 👆 is known just as chicken mushroom as it is the most common. These 👆 are 'torch chicken mushrooms'. And these 👆 are open umbrella mushrooms, Termitomyces albuminosus. Care must be taken when foraging these as they can easily be mistaken for Chlorophyllum molybdites, which are poisonous and can causes potentially serious vomiting and diarrhea. They are the most consumed poisonous mushroom in North America. All these are simply fried, often with ham, and often used in soups where they can take long cooking. Some people think they taste like chicken; others like enoki mushrooms. I’m in the middle. I find that mildly sweet with a slightly crunch texture 黑皮鸡枞菌, black skin chicken mushrooms are a related cultivated variety which are more widely available in recent years.

-

Any version of Amazon does the same. Not just UK. Using the one relating to your own country is generally more likely to give goods available locally. Amazon.com : spice books

-

Stuff on sticks 烤羊肉串 (kǎo yáng ròu chuàn) Spicy grilled lamb skewer 烤刀鱼串 (kǎo dāo yú chuàn) Spicy grilled Chinese tapertail anchovy This is Coilia nasus. Much larger than the anchovies you're probably used to; they grow up to 41cm / 16 inches but this one was 26cm / 10¼ inches. They are native to local waters. I ate these with some 馕 (náng), naan bread. Feel stuffed.

-

-

Yunnan Province in south-west China has international borders with Vietnam, Laos and Myanmar / Burma. Internally, it borders Guizhou, Sichuan, Guangxi and Tibet. This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license. It is renowned for its biodiversity and especially its abundance of mushrooms, with over 800 different edible varieties. Many are exclusive to Yunnan, some not so much. Yunnan Mushrooms For the next few days, I’ll post just a few starting with this: 红牛肝菌 (hóng niú gān jūn), Boletus gansuensis, Red Boletes. These are also found in Gansu province, hence the scientific name.

-

A week in Jakarta and Bunaken island, Indonesia

liuzhou replied to a topic in Elsewhere in Asia/Pacific: Dining

Thanks I've been looking forward to your report. And so glad that, for once, you didn't get sick! Roll on, part two! -

Maybe I just like a bit of a chew. I find regular burger buns too spongy, soft and yes, sweet.

-

Right on cue. Five beef patties, four cheese slices, bacon, lettuce, tomato … Burger King’s sumo of a burger enters the ring | Food | The Guardian

-

Hmmm. Interesting. I've never had that problem.

-

Same in China. It's what I do with the Sichuan Facing Heaven type.

-

Did you know that the word 'garlic' in English is derived from the Old English gárléac from gar + léac meaning 'spear leek', so originally referring to the shoots or scapes rather than the bulb? Maybe they were more important to the English 2,000 years ago. I don't know; I wasn't around then although my great-grand children think I was!

-

I don't know for sure, but it strikes me it is much more likely to be Chinese. China exports approximately ⅔ of the world supply. 20.5 million tonnes in 2021 compared to Spain's .03 million, according to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Statistics Division (FAOSTAT)

-

This was lunch yesterday. I visited the restaurant which delivered my fish and soy bean dinner a few days back, but tried a different dish. 青椒炒田鸡饭 (qīng jiāo chǎo tián jī fàn), Green Pepper Fried Frog over rice As you can see, it also contains red chilli for heat, whereas the milder green peppers are more a vegetable component. The particular name used for the frog here, 田鸡, literally means 'field chicken' referring to them living in paddy fields.

-

Correcting myself. I've seen them in Japan and S. Korea where they definitely don't use knives and forks. They have also made an appearance in China, mainly in Shanghai and Beijing places but I've never seen them, not that I want to. China doesn't use knives and forks either and I don't think you could eat one with chopsticks! I did see a video with one clown eating by one using a spoon, though, although he ate most of it using his hands.

_svg.thumb.png.7217419d3749fa993c66e784f312fcbe.png)