-

Posts

6,345 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Store

Help Articles

Everything posted by chromedome

-

It's pretty and low-effort, so that might actually happen. If so, I'll be sure to post about it.

-

This is the first year I've had a quantity of nasturtiums, so that decision isn't quite upon me. I may do, though I don't go through capers very quickly. I'm the only one in the house who eats them, and a jar lasts me a while.

-

I planted those in my garden this year, but sadly none of them survived the erratic spring weather. I'll probably try again next year.

-

Yet another energy drink recall, this one the "Mindblow" brand sold in Ontario, Quebec and perhaps elsewhere. Apparently it contains "unpermitted" ingredients, including a herbal extract that's 98% levodopa. WTAF? That's the main medication for Parkinsonism, and decidedly not something you should be randomly ingesting. Maybe that's where the brand name comes from... https://recalls-rappels.canada.ca/en/alert-recall/mindblow-brand-energy-drinks-recalled-due-non-permitted-ingredients-may-pose-serious?utm_source=gc-notify&utm_medium=email&utm_content=en&utm_campaign=hc-sc-rsa-22-23

-

The "beans 'n' greens" treadmill continues apace. The exciting departure is that yesterday saw the first "real" - if small - harvest of shelling peas, by which I mean "more than just a handful to snack on as I work." I actually took a small mixing bowl out there and filled it with them, and in the end it worked out to exactly 1 cup of shelled peas (net of snacking, because our grandson was right there watching like a hawk). They'll be hitting full stride in another week or so, as will my fillet beans. The first half of the bed (planted earlier) is now yielding heavily, while the second half (planted later) is just on the verge of starting to yield. I know there's a separate thread for flower gardens, but I thought I should mention at some point that my "jungle o' beans" has a "jungle o' nasturtiums" counterpart along one edge of the garden: I like them in salads, but realistically their main use is prettying up the living room for my GF.

-

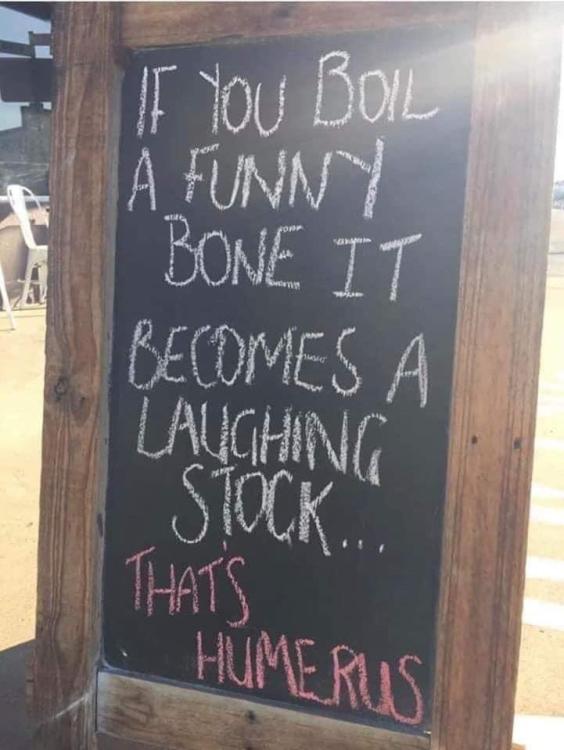

On a similar note, a sign outside one of my local pizza joints said "I must be a hipster... I ate my pizza before it was cool!"

-

Just a followup to let you all know that the auction on the donair costume has finally come to a close, with a winning bid in excess of $16,000 CDN. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/aug/16/donair-fast-food-costume-fetches-more-than-16000-in-canada-auction

-

Clearly we have patience for different things; that's my usual short answer for why I don't use the Cuise for this kind of purpose.

-

Wow, you must grate a LOT more at a time than I do. Just retrieving my Cuise from its shelf in the pantry takes longer than grating a couple of portions and dropping my grater into the dishwasher.

-

That's me as well. I have a full set of discs for my Cuisinart, which came as a throw-in with my backup machine, and I've never used even one. ...though we'll see how that changes over the years as my arthritis and tendinitis worsen. I like having them as a fallback.

-

In my case the "fairies" are called grandkids. I have hiding spots for tape, scissors, and staples, and have recently added needles to the list because our granddaughter is teaching herself to sew.

-

Garden the past few days has been more of the same, with a few more pounds each of beans and greens going into the freezer. Today was a landmark, though, because our bed of winecap mushrooms (Stropharia rugosoannulata) is finally in full flush: I haven't weighed them yet, but I'll update the post later (ETA: They weighed in at 1.526 kg, or just over 3 1/2 pounds). Also got the very first zucchini of the year this afternoon, though there are (surprise!) many more waiting in the wings. My bell peppers are coming along nicely (don't worry, they won't be harvested until ripe and red): Finally, a sequel of sorts. You'll recall seeing the photos of Senior Sea Kayaker's garlic hung up to cure, and mine spread on repurposed bread trays for the same purpose. Here's the pic from immediately post-harvest, with today's photo beneath: The curing process is partly about letting the bulbs dry, so their skins can assume the proper paper-like, protective texture, but it's also about the bulbs cannibalizing the nutrients left in the stems and leaves. That maximizes the storage of sugars for next year's growth, and incidentally also maximizes flavor for human consumption. I dug over the garlic beds earlier, put down corrugated to subdue the weeds, and covered the cardboard with new topsoil. Now that a little spate of rain has ended, I'm going to head out and replant them in spinach and kale. I've had poor success with spinach in spring, here (the weather's too uncertain) so I'm hoping that an autumn planting will work for me. Warm weather for germination and early growth, then cool weather when it might otherwise bolt. It sounds good, anyway, and worked last year with cauliflower.

-

Inevitably, Someone Used AI to Generate Recipes. It... Didn't go Well

chromedome replied to a topic in Food Media & Arts

Mind you, the same could be said of many humans. -

"Soft Serve On the Go" ice cream cups are being recalled in Ontario and Quebec for potential listeria. https://recalls-rappels.canada.ca/en/alert-recall/soft-serve-go-brand-frozen-dessert-cups-recalled-due-listeria-monocytogenes?utm_source=gc-notify&utm_medium=email&utm_content=en&utm_campaign=hc-sc-rsa-22-23

-

The numbers are, on the whole, slightly better for "lab-grown" as opposed to "cell-cultured," the latter of which is now (just recently) the officially-preferred nomenclature. Go figure.

-

Well here's an interesting bit of insight into consumer opinions. The blog is from a prof at Purdue, and there's a link in the blog post to the underlying research paper. The part that's highlighted here in the blog post is a survey of consumer attitudes toward beef vs. plant-based alternatives, cell-cultured meat and lab-grown meat (the latter are the same, but researchers wanted to see if the differing labels translated to differing perceptions). Most of the responses were pretty predictable, but one of them simply floored me: 38% of respondents rated beef above meat-based substitutes for animal welfare. Not sure what kind of mental gymnastics go into that... http://jaysonlusk.com/blog/2023/8/9/beliefs-about-beef-vs-plant-based-cell-cultured-and-lab-grown-alternatives

-

Yup. There's an occasional one in there that missed its moment (you never quite find 'em all, which is why I try to go no more than two days between picking) but mostly they're prime. Now that the more-delicate filet beans are hitting their stride we'll primarily be eating those, and freezing the conventional ones.

-

I mentioned a little way upthread (a few months ago, now) that we'd been losing random adolescents mysteriously, and that I'd blamed it on a shaky adjustment to our new waterers. That proved not to be the case, and I was unable to match the symptoms to a specific disease. We'd even begun reading up on which plants might be in our yard that could conceivably be toxic to the poor bunnies, thinking that this might explain the randomness (and the fact that it hadn't impacted our indoor bunnies). In the event, our last harvest finally provided the "smoking gun." Because they're raised for meat I do - in effect - an ad hoc necropsy on every rabbit we harvest, and I've occasionally seen livers that looked mottled, like the marbling on a good steak. This last batch had several whose livers looked that way, and this is when the penny dropped for me. It turns out to be hepatic coccidiosis, a parasite spread through their droppings (remember me mentioning that they're coprophages?). We can still safely eat the bunnies (phew!) and our dogs won't become ill from snacking on the bunny droppings (these parasites are species-specific) so that allayed our immediate fears. It also tells us our countermeasures, which boil down to improved cage hygiene. That in turn means some tweaks to our cage design, to improve the feces' proverbial ability to move downhill. Mostly these are things we'd already discussed, because on a practical basis cage-cleaning takes time and energy: if it can be minimized, so much the better. And if it protects against coccidiosis (it does), better still. As for the affected bunnies treatment is to keep them hydrated and fed, by syringe if necessary. Many get over it handily enough, and many are asymptomatic (ie, most of the last litter I harvested), and adults are largely unaffected. It's just the adolescents who are really vulnerable, or rabbits who are already suffering from health issues. This was timely information, because this morning when I went to feed the little guys I found one of our indoor bunnies sprawled on its side and showing the symptoms I've come to recognize (floppiness, lethargy, etc). We've not had an indoor bunny get sick before, so this was a new development and an unwelcome one, especially as I'm rather fond of this litter (they're all very personable). So currently the little guy is in a box here in my office, a couple of feet away, and I've just given him his second watering from the syringe. He's starting to perk up a little, but still seems pretty subdued. I've put a couple of dainties in the box, to tempt his* tummy, but if necessary I'll feed him through the syringe as well. For this morning that'll have to be unsweetened applesauce, the only rabbit-friendly thing I've got that can be administered this way, but apparently it's possible to cook up the alfalfa pellets into a sort of loose porridge that can be syringed into convalescents. We'll see about that later, if it should be necessary. More later, but right now I'm supposed to be working. *Not verified, but in my head this one's "Max" after the childrens' books and TV series about "Max and Ruby."

-

Another 8 pounds of green and yellow beans yesterday, plus a decent quantity of salad greens from the remnants of my first planting and my burgeoning third planting. Bread in the frame because that's where it was cooling, and I couldn't be bothered to clear one of the other flat surfaces in the vicinity to move it (I live with grandkids, things often repopulate the clearing-in-process surface during the time it takes me to drop something in the next available surface. Or, you know... put it away. That happens too.). The bread's a bit misshapen because I was laser-focused on the article I was writing, for once, and it over-rose while waiting for the oven.

-

Across the border here in Atlantic Canada, lobster fishing closes each year during moulting season. Apparently it's not actually illegal to harvest soft-shells here (which was the impression I'd garnered), as long as it's done during the season, but the limited numbers available just before and after closure (and the lower price for soft-shell lobster) means that they're seldom harvested in practice.

-

Harvested a first hatful of my filet beans last night, but didn't grab a picture. They were the side with dinner (nothing fancy, just butter on 'em).

-

Damn. Nobody ever gives me free eggplant...