-

Posts

16,764 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Store

Help Articles

Everything posted by liuzhou

-

It looks the same as the one I bought in France 45 years ago, except mine is the classic orange colour. I'd need to measure mine to be 100% sure but it's in my daughter's kitchen on the other side of the planet.

-

I'm not a chocolate lover, never mind a chocolatier. so I very rarely venture into this part of eG. However, I thought this may be of interest to at least some of you. (That said, you may already know and I'm just miles behind the times, but no one has mentioned it that I can see.) Scientists develop method of making healthier, more sustainable chocolate

-

I will add to this by quoting @KennethT The same in south Asia and many other places. Always get reliable local information from qualified sources!

-

This issue came up again yesterday in the Dinner 2024 topic. I was asked by @KennethTabout my local water supply here in China. In general, the advice given is not to drink the local tap water anywhere in China. Few people, including me, ever do. When I first came here (1996), I didn't even brush my teeth with tap water, but was never concerned about washing vegetables with it (not logical, I know). I would use bottled water for teeth and for drinking. I soon gave up the teeth related usage. As someone mentioned on the thread yesterday, people do get acclimatised to the local water and less prone to negative reactions. So, when I get visitors from Europe or North America, I advise them to stick to water for teeth cleaning and to only drink bottled purified water. Ice cubes in bars are made from purified water and safe. Local Chinese friends simply don't believe me when I say the water in the Uk is generally safe to drink. A couple of disgraceful water pollition scandals in Britain in recent weeks have only confirmed their views. In more rural settings in China , people always boil the local water. In fact, trains and hotels always have supplies of boiled water available in samovars on trains and vacuum flasks in hotel rooms. Many people even in cities still hold on to their flasks. I found one in this rented apartment when I moved in. 4 litre vacuum flask I can buy purified water in large (19 litre) bottles for use with this type of dispenser – most people have them at home, as do I refills are cheap and delivered to the door. Additionally, I buy in these 555ml bottles for convenient portability. I buy in boxes of 24, again delivered to my door. China has very little ‘mineral water’ and no sparkling / carbonated water, although imported Perrier, Evian, San Pellegrino etc are available, though expensive at up to five times the price of local brands. But nearly all the local waters are ‘purified’. The only time I’ve had a problems with water, albeit a serious one, was in 2012 as reported here in an article I wrote for a Beijing media company. The ‘problem’ lasted less than a month. Yizhou is a small city in Hechi Prefecture in the north west of Guangxi. It is a sleepy sort of place which has yet to benefit from the development being carried out elsewhere in Guangxi. It is popular with the locals in summer as it lies in beautiful karst scenery similar to that of Yangshuo, but definitely much less touristy. There are many riverside fish restaurants, but most popular are the boat rides along the Longjiang River, some of which drop you off at “minority villages’ where you can partake in mock marriage ceremonies. I’ve been “married” there more than once. Never saw the girls again. The first village I visited was actually built as a movie set and no one really lived there. Apart from that, nothing much really happens there, although in 2008, it made international newspapers when twenty people were killed in a chemical factory explosion. Now it has hit the headlines again. On January 15 2012, alerted by the discovery of hundreds of dead fish in cages in a reservoir on the river, local authorities tested the water and discovered cadmium levels higher than the permitted safety level. Cadmium is a highly toxic heavy metal used in batteries, electroplating and in some industrial paints. Exposure can lead to kidney failure or cancer. On Thursday January 19, the Hechi government issued a statement saying that the cadmium level at Luodong Hydropower Station at the river’s lower reaches was 0.0247 mlligrams per litre, three times higher than the official limit. Other reports also mentioned that arsenic levels were above permitted levels. The authorities warned local residents not to drink the water and ordered dams to be opened to dilute the chemicals and hopefully bring levels back to normal. They began dosing the river with dissolved aluminium chloride in an attempt to neutralise the contaminants. At the same time, they started digging wells and arranging other alternative water sources. Investigations later revealed that the pollution was caused by a discharge by Guangxi Jinhe Mining Company, which operates upstream. After flowing past Yizhou, the river meanders west before joining the much bigger Liujiang river which then flows south to the first major city in its path — Liuzhou, Guangxi’s industrial centre. The river loops through the city centre and is the venue for international water sports events etc. Thereafter, it flows south east, eventually joining the Pearl River. Several years ago, it was possible to take a ferry from Liuzhou to Guangzhou, but no longer. The news from Yizhou also trickled down to Liuzhou over the Chinese New Year weekend and Monday’s New Years Day. I first read about an outbreak of panic buying of bottled water on Tuesday January 24 but I visited the city’s three largest supermarkets that day and saw no sign of anything unusual. By Thursday, the news had reached the wire services and appeared on the BBC news site. By then, people really were panic buying and they still are. This morning (Friday 27), I visited the two largest supermarkets in the city centre. Nancheng department store had completely run out of bottled water but in Lianhua Century Market, people were queuing up with stacks of boxes of bottled water piled up in their trolleys. My local corner shop, also operated by Lianhua, is completely out of water, too. It is only today that the local media are beginning to report anything about this, perhaps out of their usual reluctance to print bad news, or perhaps because everyone is still on holiday. Liuzhou authorities are saying that pollutant levels in the Liujiang are well within safety limits and urging people to behave calmly. At the same time they say they are monitoring bottled water supplies and trying to ensure that there are no illegal price hikes as happened in March of last year when people idiotically began panic buying salt to supposedly prevent radiation poisoning in the wake of the Japanese nuclear accident. There is a long tradition of swimming in the Liujiang. Every day, no matter how cold, elderly men and women can be seen slowly swim long distances up and down the river, trailing their clothes behind them in floating boxes. Today, when I walked by the riverside, there were none. And I don’t suppose the locals will be buying much fish this week. Update: At 23:36 on Friday January 27 2012, Liuzhou officials sent this message to all cell phones in the city. Don’t worry about your tap water. It’s safe. If it becomes necessary to control the water supply, we will give 24 hours notice via the media. 温馨提示:只要水龙头拧开出的水,必定是合标的安全用水,请大家放心使用 在控制供水之前24小时,将通过新闻媒体提醒您储存好备用水。【代柳州市应急指挥部信息发布组发】 Now, I just stick to drinking beer.

-

I never drink the tap water, but happily clean my teeth with it and wash vegetables. Most people do the same. Never had a problem with it. I guess it varies from place to place, though.

-

Burger in a homemade jiamo bun. The first of two. I had vaguely considered making some fries but it's too damn hot - 35℃ in kitchen before turning on any cooking equipment.

-

A pictorial guide to Chinese cooking ingredients

liuzhou replied to a topic in China: Cooking & Baking

I don't know, sorry. First time I remember seeing that. I do know that if they are, then there is a legal obligation to state so, though. -

I'd be surprised but few, if any, companies making curry powders give their precise ratios of the ingredients. They're all possible different. That's true of all curry powders: Indian, Japanese, Burmese, Thai etc. Also, regulations on ingredient listings are different in different places. In places, spices can just be listed as 'spices'. most usual though is from highest amount to lowest.

-

Yes. On the rear label. In Spanish, English, and Chinese.

-

A pictorial guide to Chinese cooking ingredients

liuzhou replied to a topic in China: Cooking & Baking

I've mentioned dips here several times. They are routinely served with almost every meal here, at home or in restaurants. What I haven't mentioned is dry dips. These, too are very popular especially with bbq's / grilled meats or hotpots. Usually a mixture of salt, powdered cumin and chilli powder or flakes. I recently came across this tiny 3 gram sachet of 四川干碟 (sì chuān gān dié), Sichuan dry dip, with a bizarre ingredients list. My translation. Dried chilli, rapeseed oil, white sesame, soybean, peanut, MSG. Edible salt, pepper (irradiated), sugar, chicken essence mixed with hemp material, spices (irradiated), flavor. On sale for an outageous ¥0.88 / 12 cents USD. I however had it delivered along with a heap of other stuff and they only charged ¥0.01 / $0.0014 USD. I guess that's as low as the system allows them to go. Still a rip-off. I can mix it myself without all the crap for even less. -

I went down the chardonnay trail last night. Ot maybe chardonnay tail. Despite the kangaroo or wallaby (?), this is Chilean. Cheap at the equivalent of $9.39 USD, but acceptable. It was a gift.

-

Like almost everyone here in the largest rice eating country in the world, I don't use cup measurements. Totally unreliable. For rice/ water ratio, I tend to use the first knuckle of the index finger method as do my neighbours. That said there are many factors involved in rice cooking. Even two batches of the same rice can be quite different. How it's stored, how old it is, what variety it is, the weather! Every time I get a new bag (I usually by 5 or 10 kg bags) I test and adjust. Then I consider how I'm going to use that rice. A drier rice works better for fried rice. Much wetter for congee 8:1 Water:rice.

-

I agree with the above. The problem is it's turkey. Why have you been making them for years if you don't like them.

-

This page outlines what topics go in what forums. I'd say this goes under Cooking If you report your post, I'm sure @Smithy will move it to where it should be (and hide this).

-

Prawn fried rice with (mostly) SE Asian herbs: culantro, coriander leaf, Thai basil, Chinese chives and non-Asian rocket / arugula. Chili and garlic, Chinese fish sauce.

-

I have two small rice cookers which each do about two servings. They are, of course, Chinese and were very cheap. I bought the first about 5 years ago or more, but when I moved house in January this year couldn't find it in the jumble of boxes littering the new place and wanted to eat that night, so I bought the second. They're that cheap here - almost disposable. This it the 2nd one. Cooks 1-4 cups of rice; I usually just do one or two. I'm pretty sure the names of the specific brands would be of no use to you, but I'd check out a Chinese or generally Asian market if you have one nearby.

-

How would I know? Oh! You don't thing I bought them, do you? 🤣🤣🤣

-

It is normally only used with seafood. I elaborated on this serving style on this topic .

-

Unfortunately, that doesn't seem to be for sale.

-

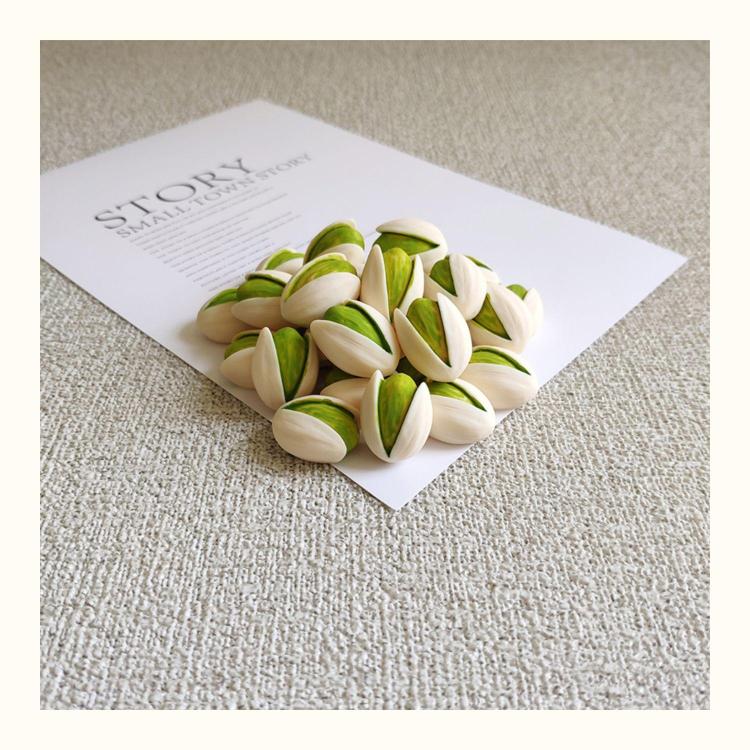

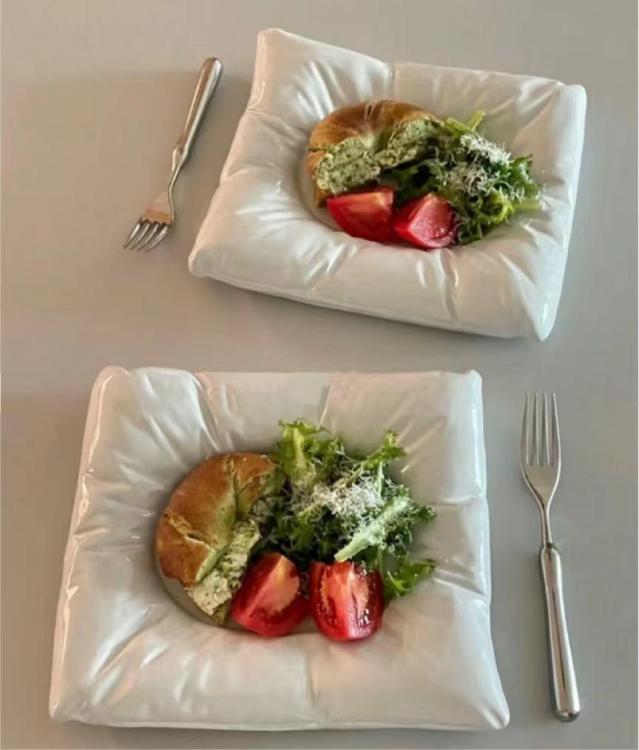

Astonishingly often, I come across strange food themed oddities, mostly on Taobao, China's largest online shopping portal (part of the Alibaba group). I'd like to share some of the most amusing or bizarre. Kicking off with a pistachio. Well, a pistachio pin / badge. These come at a whopping ¥8.39 / $1.16 USD a nut. Real pistachios are around ¥20 / $2.76 for 100 grams. Made here in China. Next, also Chinese, are salad (or whatever) bowls resembling pillows. I often rest meats; never salads. Maybe that's what I've been doing wrong. Bedding down your salad will cost you ¥100.78 / $13.93 a bowl. Finally for now, this time from Japan is the strangest (in my estimation). A half eaten hamburger. When I first saw this image, I thought it was a giant burger cushion but no. It's hamburger sized. Ths nonsense costs a whole ¥500.77 / $69.21. For that I could buy 15 real burgers from McD's. More to come as I spot them.

-

Pork tenderloin cubes marinated in EVOO, lemon juice, garlic, chilli and crushed (roasted) coriander seeds. Stir-fried in the marinade. Served with a simple white onion, tomato and coriander leaf salad and rice.

-

Nice. Originally खिचड़ी in Hindi (khichri and various other transliterations), kedgeree was described by visitors to India hundreds of years ago, long before British rule.. The Arab traveller Ibn Batuta wrote in 1340 that The word for lentils in Hindi, दाल। (daala) covers many more species than the English and includes mung beans. Under British influence and for British Raj colonialists, flaked fish or smoked fish replaced the pulses and chopped hard-boiled eggs came into the dish. Fish-based kedgeree is still popular in the UK and even in India. I was served an excellent version several years ago in Kolkata. I’ve often thought of making it here in China, but the only smoked fish I can source is much more heavily smoked / cured than that used in India or the UK and tends to overpower the spices in the dish. I know it can be made with fresh, unsmoked fish, but for me the whole point of kedgeree is that smokiness. I occasionally make the traditional version with lentils, but with fish I tend to just go for a Chinese fried rice.

-

I think this is a UK site, but of universal appeal. We Want Plates.