-

Posts

1,832 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Store

Help Articles

Everything posted by vengroff

-

Thanks, Doc. I do provide an advanced customization screen that allows you to override all relevant input variables. You can use that to set the surface heat transfer coefficient as you wish between 50 and 1200 W/m^2-K. That being said, most users will rely on the built-in values tied to particular equipment that are chosen from the main setup menu. These include 95 W/m^2-K (Sous Vide Supreme), 155 W/m^2-K (Sous Vide Professional), and fixed values of 200, 300, and 600 (the values I most commonly see in the literature). If you happen to know the coefficients for the Lauda machine you have, please let me know and I'll be happy to add them. If you know them for the different pump speeds, so much the better. The app is in beta now and should be publicly available in the app store soon.

-

Thanks, Nathan. It surprises me too, but sometimes linear regression works well even in places you don't expect it to.

-

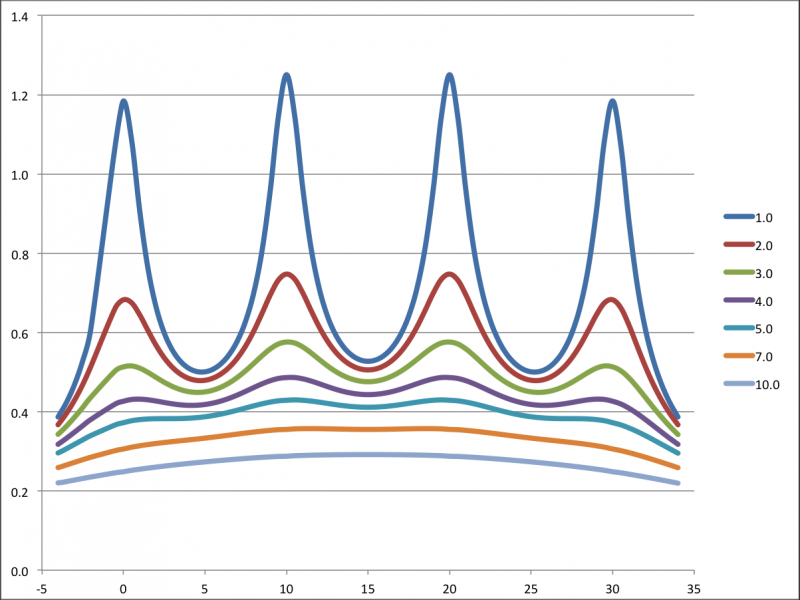

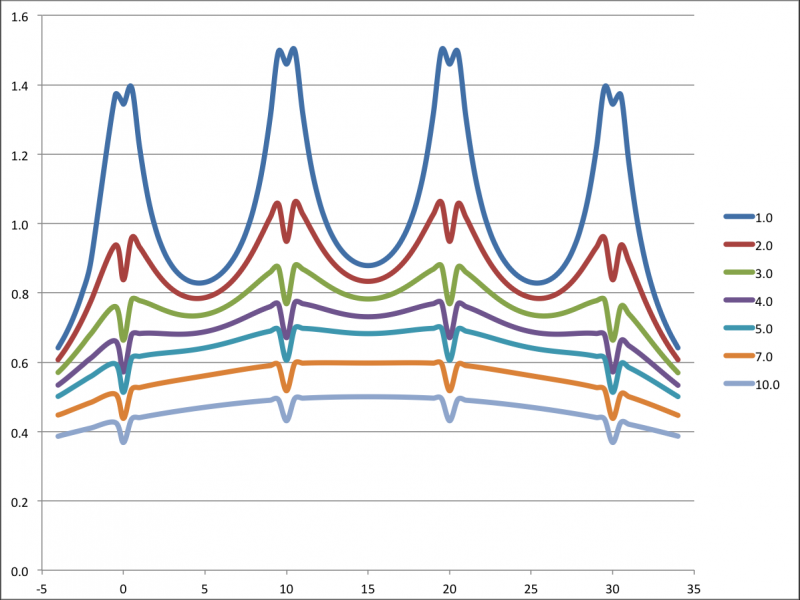

Interesting. I haven't tried it, but my gut feeling was that putting the food that close to the broiler would end up burning things - pretty much your experience. I was curious about the broiler rule of thumb when I read it too. The thing that I couldn’t understand was how the distance from the heating rods to the top of the oven was not a variable. I modeled the system myself and found that under my assumptions* this distance mattered. I also couldn’t come up with a good explanation for the 44% of spacing plus 5mm rule. Here is what I found. If the top of the oven is really far from the rods, or is non-reflective, then things look like you might initially guess. I plotted the relative amount of infrared delivered across the food, from left to right across the oven, assuming the oven has four heating rods spaced 10cm on centers that run front to back within the oven. There is one curve for each of several distances between the rods and the food. The top one is for a distance of 1cm from the rods to the food and the bottom one is for a distance of 10cm from the rods to the food. The ones in between are for distances as indicated in the legend at the right. As you can see in the following graph, the heat is most intense directly under the four rods. You can see from the graph exactly where the rods are. Now if we account for reflection from the top of the oven, things change a bit. Now we get more infrared hitting the food in between the rods but less directly below them due the shading effect MC describes. This is shown in the following graph, which models a reflective oven top 3cm above the rods. So what does all this tell us about the so-called sweet spot? First of all, as MC tells us, we can’t put the food too close or we get big spikes that will burn the food before it cooks in other areas. The top few curves clearly demonstrate this. But even these curves show shade effects directly below the rods. There are also second-order shade effects where the reflected heat from one rod is shaded by an adjacent rod, but they are smaller and I did not model them. Further from the rods, the curves are smoother and flatter, but still have the shade effects on the order of 15%. The good news is they are quite narrow, so you can cut the effects in half simply by sliding your food to the left or right a couple of centimeters halfway through the cooking. Do this three or four times during the cooking, always in the same direction, and the shade effect should be effectively eliminated. I'd love to hear how the MC rule of thumb was derived and what assumptions were made. Also happy to hear feedback on my results. --- *My assumptions are that the heating rods are long enough and the food is sufficiently far from the end that their infrared radiation can be modeled by a 1/r rule and that the top of the oven is completely reflective in the infrared part of the spectrum.

-

"Modernist Cuisine" by Myhrvold, Young & Bilet (Part 3)

vengroff replied to a topic in Cookbooks & References

After all the talk of their heft, I thought I'd have a new heavyweight cookbook champ when MC arrived. And I certainly do if you consider the whole set as one. But for individual books, volume 2, at 3230g, comes in just behind my copy of Culinaria Italy, at 3260g. The other four volumes are all under 2900g. Culanaria Spain, Culinaria France, and The Professional Chef, 7th Ed., on the other hand, are all over 3100g. The good news is MC, though a few cm taller, will fit on the shelf with these other monsters. Mass aside, the books are stunning. They are both beautiful and informative. -

Seattle, WA Technology Exec. Amateur cook who does the occasional pro-am charity event. Trivia: When I was an undergrad I was an intern at Microsoft in the group that had been Nathan's company before MSFT bought them.

-

Sharp makes a convection/steam/microwave combination targeting the home market. It runs just under $1000. I don't know how it compares to the pro units but the price point is certainly lower.

-

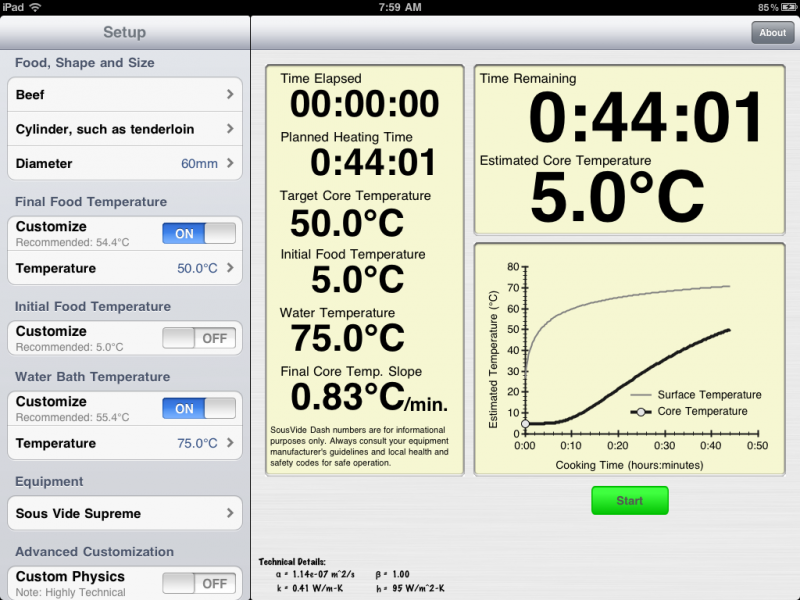

Peter, It may be too late at this point, but based on your description of your approach, here is my best approximation of what will happen, subject to the water staying at 75°C, which is obviously a big assumption. The key point here, as Pedro and Nathan indicated, is that timing becomes very critical with overly hot baths. At the time the core reaches 50°C it will still be rising at 0.8°Ç/minute, so getting the timing right is critical. Note also that this is for a 60mm diameter filet. If I change it to 61mm, then the time goes from 44:01 to 45:20. So at a high temperature like this even something as simple and getting the diameter slightly wrong makes a big difference. Given the option, cooking 0.5-1.0°C above your target makes way more sense than cooking at 25°C as in this example. But I think you already knew that at are in a pinch. Hope this analysis helps.

-

Just to get things perfectly straight, mass is not volume. They are different. Mass is the amount of matter in an object. Volume is how much space it occupies. The ratio of these two is density (= mass / volume). A marshmallow and a pebble might have the same mass, but the marshmallow has a much larger volume and lower density than the pebble. Weight and mass are often confused because we typically use scales to measure both of them. But weight is not mass. Weight is the force exerted by the earth's gravity on an object. In a fixed gravity environment, weight is proportional to mass, which is why we can measure them using the same tool. If we took the marshmallow and the pebble to the moon, their mass would remain the same, but their weight would be lower than it is on earth.

-

My last -- and anyone's best -- shot at elBulli

vengroff replied to a topic in Food Traditions & Culture

Fantastic. I can't wait to hear how it goes. -

"Modernist Cuisine" by Myhrvold, Young & Bilet (Part 2)

vengroff replied to a topic in Cookbooks & References

I happened to be in the vicinity of the Pacific Place BN store in Seattle this afternoon so I stopped in and asked about this. They pulled up the book on their computer and next to the $461 price it said, "no further discounts available," in big red letters. I showed them this post on my phone and they told me it was up to the store manager's discretion whether to allow the discount. In the case of this particular store the answer was no. My Amazon shipping window begins this week, so I'm hoping I don't get the dreaded email pushing it back. -

I haven't seen exactly this proposal before, but I have certainly seen people advocate putting the eggs in cold water, bringing it to a boil, then immediately shutting it off and holding it for some number of minutes. The Joy of Cooking, for example, advocates this technique. I suspect it is possible to come up with more than one water temperature over time curve that generates the kind of gradient you described to cook the white, then drops the water temperature to allow just the right amount of heat to reach the center of the yolk. If it can be done with a quantity of water at a fixed initial temperature in a well insulated vessel as you describe, that would be even better. I have contemplated the non-constant water temperature approach for a number of applications, but I have never followed through. Mainly it's because I think it would require something more sophisticated than an off-the-shelf PID to control properly.

-

Windows Phone could be an option in the future, but Excel is probably not. The style of simulation required doesn't lend itself well to a spreadsheet. It isn't just a series of formulas, but rather an iterative process where for each of a large number of very short time intervals from the time the food enters the water until it is done you have to solve a relatively large set of equations. I'm sure it could be done with some clever VBA, but it's not really the sort of thing Excel was built for. I've got a small number of bugs to work through but I'll probably submit it to Apple in the next couple of weeks. We'll see from there how long the approval process takes. Initially it will be for the iPad, but I will also try to rework the UI for the iPhone. Thanks to both of you for the support.

-

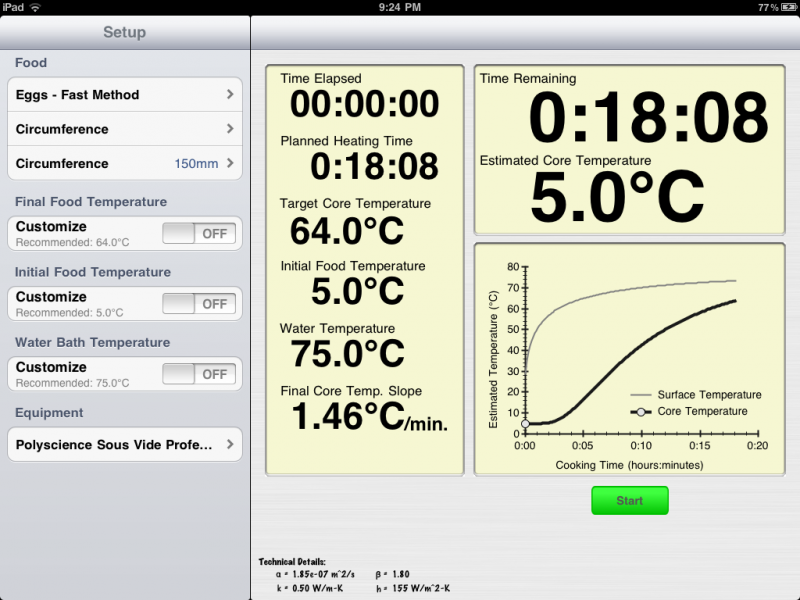

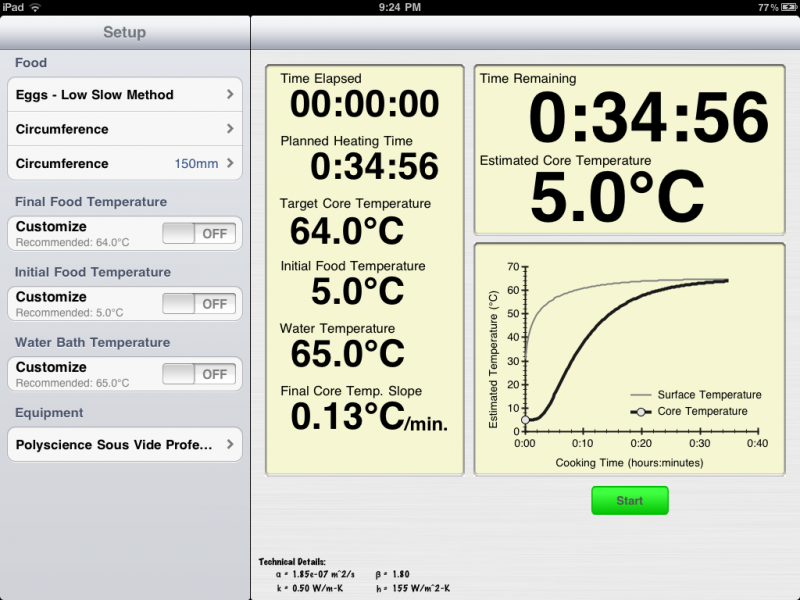

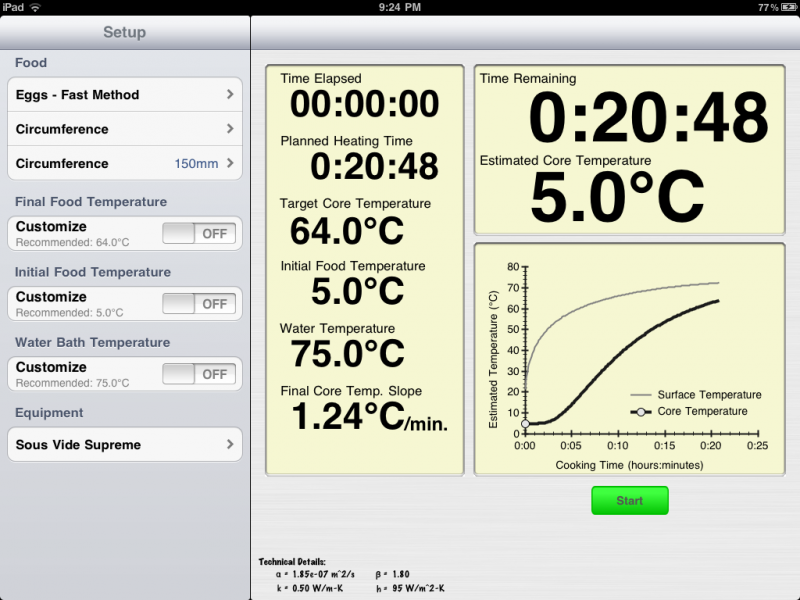

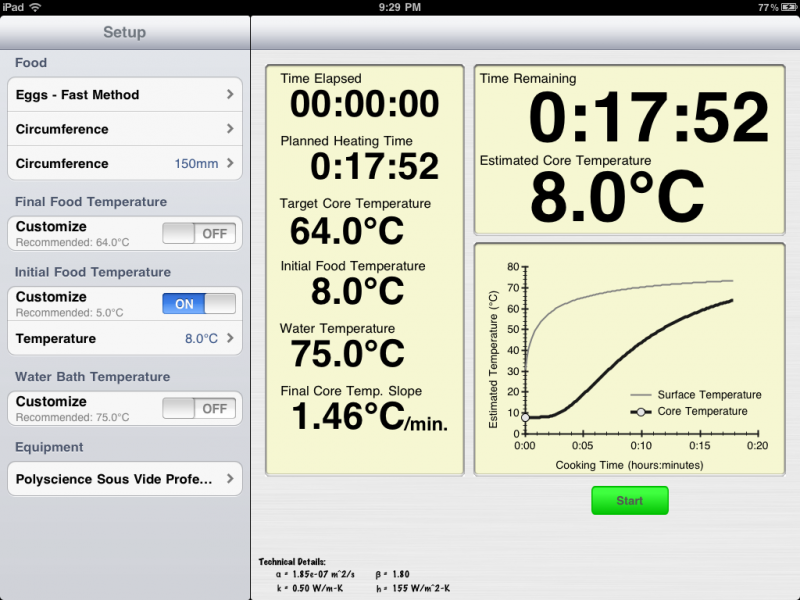

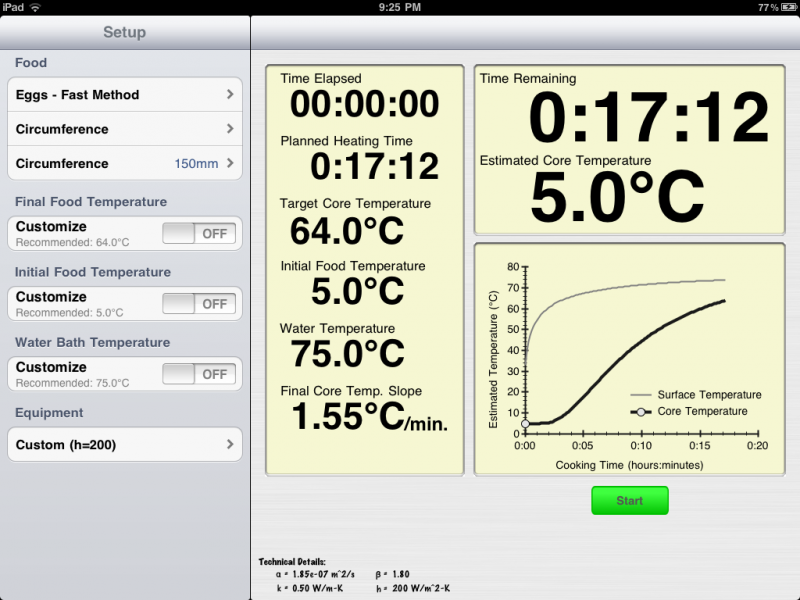

I love sous vide eggs and until recently always used the slow cooking method. But I’ve been experimenting with 75°C water and have had some very good results. The most critical thing to know about the faster method is that when the center reaches the target temperature it is still moving up pretty rapidly, so pulling the eggs out at exactly the right time is critical. There are other factors that matter a lot too, like whether you use a circulating or non-circulating bath, and some that are far less critical, like the exact starting temperature of the eggs from the refrigerator. I actually modified my iPad sous-vide dashboard a little bit to make the rising temperature effect really clear. Here’s a screen shot of the dashboard configured for an egg of 150mm circumference and 75°C water. First, notice that in the graph the core temperature (the thick dark line) is still rising rapidly at the end of the cooking time. This means that if you leave the eggs in for an extra minute or so, their temperature will rise quite a bit relative to your actual goal. This is very much in contrast with the more common sous-vide approach that produces a nice soft landing at the target temperature by using a bath only 0.5-1.0°C warmer. Exactly how fast the temperature will be rising at the end of the cooking time is given by the number 1.46°C/min., which tells us that if we leave the egg in an extra minute the core temperature will rise quite significantly. In contrast, consider the lower temperature approach shown here: In this case, the core temperature curve has the more classic shape where it slows down a lot as it reaches the target temperature. In this case, it is rising at only 0.13°C per minute. For larger eggs, this number will be even smaller. For large cuts of meat, like beef tenderloins, this number can be well below 0.1°C/min. at the point the meat reaches temperature. If we look at what other factors can affect the outcome of eggs, we find that one of the most significant has to do with the type of equipment used. In the examples above, I had my dashboard set for a Polyscience Sous Vide Professional. If I switch to the Sous Vide Supreme, which does not have a powerful circulator, and go back to the 75°C method, things take longer because without circulation the water does not transfer heat to the food as efficiently. The difference in time between the two machines is 2:40, which at a rate of approximately between 1.2 and 1.4°C/min. means a significant temperature difference. If I used the Sous Vide Supreme numbers for the Sous Vide Professional or vice-versa I would not get the results I hoped for. It is thus critical that I use times tailored to my specific machine. Another factor that we might think would make a big difference is the initial temperature of the eggs. However, this does not make nearly as big a difference as the machine or the exact cooking time in the 75°C case. In the example below, I raised the initial temperature of the eggs from 5°C to 8°C and the cooking time was only reduced by 16 seconds. So food safety issues aside, you don’t have to worry much about your refrigerator not being adequately cold. Finally, just as a test case to make sure my calculations are not off the rails, I duplicated some Douglas Baldwin’s table scenarios and got results to within a matter of seconds. For example, here is the case from his table for a 150mm circumference egg in 75°C water with a custom circulator somewhat more powerful than my Sous Vide Pro (h=200 W/m^2-K vs. 155 for the technically minded): Douglas’ table says 17:10 for this case, whereas my dashboard says 17:12. I’m happy with this, as there are probably subtle differences in how we handle some of the technical details of the simulation that could account for a difference this small. I was originally planning to just use this dashboard to fill in some gaps in the tables, but I’ve since found that by playing around with it I have gained a much better understanding of the dynamics of sous-vide cooking and what factors have the greatest influence over the quality of the results. I certainly expect to cook even better eggs in the future as a result.

-

Thanks Douglas. Your web page is quite informative and helped me a lot. I realize now that it's not obvious from what I showed, but when you select a food you can also select a shape. The data model has a different beta for each shape, but I've mostly only tested with the flat slab (beta = 0) case. By the way, do you have any experimental evidence for a good beta to use for a chicken breast? I suspect it's somewhere in the 0.3 to 0.5 range. What about a squat not-quite cylindrical roast--the kind of large cut one might tend to sous-vide? Somewhere in the 1.5 range? I initially tried Dirichlet boundary conditions but the results were disastrous. I tended to get times that were way short of the mark. The other thing I tried more recently, based on the tables you and Nathan put together, was to reverse engineer the constants you used by doing a Levenberg-Marquart least squares optimization over the parameter space. I could get good fits if I held h and k constant, but if I didn't there was a gradient that drove them off in very weird directions. Adding a Pasteurization curve is also a really good idea. I'll look into it. I'll also add an option to select between your two h values. Thanks again for the help and pointers.

-

Thanks. I'm looking into it. I tried to structure the app so it can run effectively on different display sizes. The iPhone port is a future weekend project.

-

That is correct. The example was just an illustration of the app showing you why you probably don't want a bath that hot. What happens in this case is that the surface temperature gets quite a bit higher than the center, so after you pull the food out the temperature equalizes somewhere in between the core and surface temperature at the time it was pulled. A second curve showing the surface temperature might help illustrate this.

-

Dinner out this Saturday on Capitol Hill

vengroff replied to a topic in Pacific Northwest & Alaska: Dining

La Bête, Spinasse, Sitka and Spruce, and Anchovies and Olives are all good bets. -

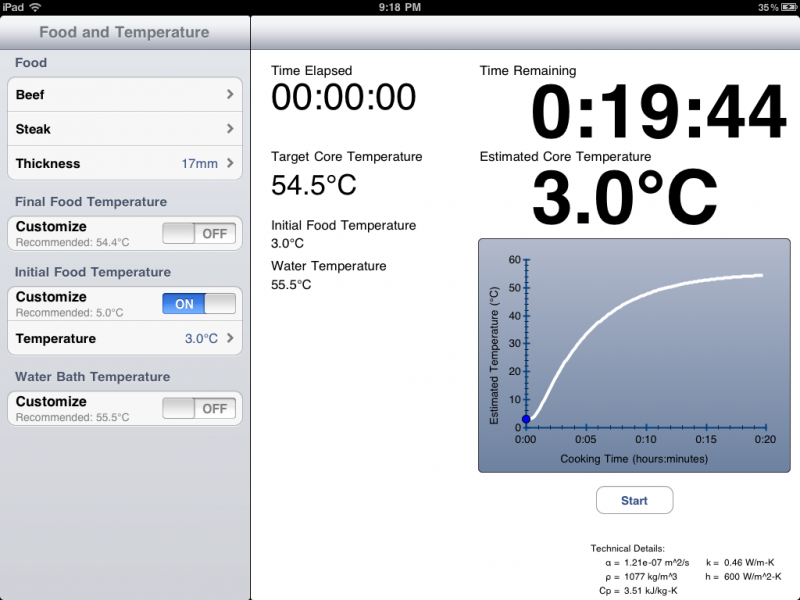

Sous vide tables, like these are a great help when it comes to planning and executing dishes. But with modern tablet computers we can do even better. This is especially true if you want to use water temperatures or food dimensions that don't appear in the tables. A while back I wrote a program to calculate sous-vide times by numerically solving the heat equation. I think it's basically the same thing Nathan Myhrvold and Douglas Baldwin did to create their time and temperature tables. Over the last couple of weekends, I wrote an iPad app around it. An iPad is more than powerful enough to solve these necessary equations, typically in under a second. Here's what the app looks like: It's a simple UI. On the left, you can choose your food, the dimensions of the food, the initial temperature, desired temperature, and water temperature. Defaults for all three are available, or you can choose to customize them, as I did with the initial food temperature above. One the right, you see a projection of how long it will take to cook and a graph showing how the temperature will change over time. Hit the start button when you drop the food into the water bath, and the app becomes a timer that counts down the time and tracks the estimated temperature. Here is a snapshot from a little over halfway through the cooking time: The blue dot represents the current time and temperature. It moves slowly up the white line as time goes by. Using the app, you can play with a wide variety of scenarios, and see what makes sense and what doesn't without wasting a lot of food. Here's an example with an extra-hot water bath: We immediately notice that although the steak will quick very quickly, the temperature will not level off like it did in the previous examples. This means that we have a very small window of time to take it out of the water without overcooking it, and even if we do pull it right when the core reaches 54.5, it will still drift upward while it rests. To get it right, we would actually have to pull it out well before the core hit the desired final temperature. The app doesn't calculate that for you, because I don't think many people cook that way, but I suppose it could. Anyway, I've been using this app on my iPad and it has worked well for me. I'm contemplating cleaning up the UI a bit over the next few weekends and then putting it in the app store. But I thought I'd throw these screen shots out for feedback before I do. Please let me know what you think.

-

"Modernist Cuisine" by Myhrvold, Young & Bilet (Part 2)

vengroff replied to a topic in Cookbooks & References

I completely agree. -

"Modernist Cuisine" by Myhrvold, Young & Bilet (Part 2)

vengroff replied to a topic in Cookbooks & References

Do you think you will be able to have a third printing in the channel in time for the 2011 holiday season? I'm sure there will be a spike in demand for gifts at that point. If you increase the size of the second printing you can lessen the risk of missing that demand. -

"Modernist Cuisine" by Myhrvold, Young & Bilet (Part 2)

vengroff replied to a topic in Cookbooks & References

I read Ruhlman's review last night, and while I see the populist angle he was going for I think he could have gone another way and been much more effective. I haven't gotten my hands on a copy yet, but to me this seems like the kind of book best reviewed after a year or so, not after two weeks. That's when you a reviewer can seriously talk about how and why it has changed their life in the kitchen. But, of course, the NYT doesn't want to wait a year to publish a review. That's why Ruhlman was, or could have been, a brilliant choice. He actually has quite a bit of experience with a number of the techniques covered, and so although he had to pick them up without the benefit of the book, he could have written a good chunk of the one-year review by weaving together his own longer-term experiences with the comprehensive treatment the book offers. That's a review I would have much rather read, and I think if done right it could have played well to a mass audience as well. -

Pike Place Market for non-tourists

vengroff replied to a topic in Pacific Northwest & Alaska: Cooking & Baking

This is opening Wednesday, June 18 at 7 A.M. ← I walked by this morning. You can see the produce section from the entrance, but you can't get in because they are still working to get the escalators going. There is a sign saying they hope to open later today. -

See here, here, and here. And be sure not to miss Colville Street Patisserie, arguably the best patisserie in the state.

-

OK Steve, I'm convinced. I'll give it a try, though I may not be able to break the hour mark on the first try.

-

Is bread really that outstanding an example in this regard? There must be hundreds of other dishes that very few home cooks can produce as well as the better New York restaurants that serve them. Fish dishes are great examples. I don't have access to seafood of the quality that Eric Ripert and David Pasternack do, nor do I have their skill in preparing it, but that doesn't stop me from cooking and enjoying fish at home. I've never tried the 90 minute bread approach, so I can't comment on the quality of the result. But I can say that the best bread I ever baked was when I was baking every weekend and keeping a good clean healthy starter during the week. Maintaining that rhythm over a series of months dramatically improved both my technique and the flavor profile of the final product.