-

Posts

5,178 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Store

Help Articles

Everything posted by paulraphael

-

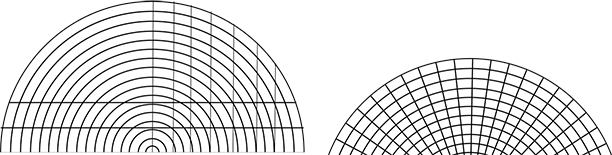

I realized this is unclear. What I mean is that if you just need a rough dice, do it the conventional way, like in the image I posted on the left, but skip the horizontal cuts. It works fine, but you'll get some long and uneven shards.

-

Thank you Caren. I suspected there were hydrocolloid gurus hiding in the shadows. Do you know much about ice cream stabilizer blends in general?

-

It would make sense to check the specs of the individual UPS, and then see what the circulator manufacturer says. But I suspect most UPSs click over in a tiny fraction of a second. How much does a decent UPS cost than supply a kilowatt? Granted, these circulators are usually asking for much less than that, but you don't want to trip a breaker when the circulator's doing its initial heating. And I don't know what happens if the circulator does ask for more than the UPS batter can provide.

-

I wonder about a software solution that uses a desktop computer in your house to act as a go-between. This would be a 3rd party software project. And maybe not so easy to set up ... you'd have to navigate firewall settings and all that. If someone could do it simply, I'd be intrigued. I'm less intrigued by the prospect of teenage hackers from Kyrgyzstan giving me salmonella.

-

You don't need all those horizontal cuts; in fact, they make your dice more uneven. They're just vestigial tails from the don't-question-the-chef era of French Classicism. One or two (or sometimes three) horizontal cuts, along the bottom edge of the onion, do make sense. They keep you from getting long flat shards from along the outer edge. How many you need depends on the size of your dice relative to the size of your onion. Small dice from a big onion means more cuts. For most onions I just make one or two horizontal swipes. (image on left) If you want very precise uniformity, there's a third way. Instead of cutting the onion in half, cut it in thirds. Set aside the middle third for the stock pot; you won't use it for this. Skip the horizontal cuts, and make your vertical cuts in a radial pattern. You can get almost perfect brunoise this way, working just with the onion's native geometry. (image on right) If you don't care about uniformity, skip the horizontal cuts altogether.

-

For now, definitely. I'm not seeking great complications and expenses. But it's fun to imagine how the next generations of slow/precision cooking tools will work. I won't be surprised if immersion circulators will seem like funny lab gizmos compared to future appliances.

-

What differences do you see with clams vs. mussels? I'm interested because I generally prefer the latter (but haven't tried either S.V.)

-

For something like this I'd trade compactness for speed and energy efficiency, by having insulated hot and cold water reservoirs. The ideal way to go from chilled to cooking would be to pump out the cold water, hold it in a cold place for next time, and pump in hot water. I can imagine this being plumbed to the hot / cold water supply, so it would be a real appliance. The water should probably be filtered every time it's pumped back into a holding tank.

-

[Modernist Cuisine] Sous vide tenderizing stage and enzymatic activity

paulraphael replied to a topic in Cooking

I'd be interested in seeing this source. One question is if the peak activity point is very close to the deactivation point. In practice, even though we don't know the mechanisms with certainty, we know that pre-cooking at 45C and 50C accelerate tenderizing. This strongly suggests some kind of enzymatic active activity, because chemical breakdown of collagen is much slower in this range than at cooking temperatures. One thing that's difficult with this kind of amateur research is knowing when you're oversimplifying. This google book chapter talks about cathespins as a whole family of enzymes. The ones listed are active above 50C, but I can't tell you if those are the ones we care about. -

[Modernist Cuisine] Sous vide tenderizing stage and enzymatic activity

paulraphael replied to a topic in Cooking

Please, I'm more than open to information that contradicts what I've posted. I've looked all over, and can find very little study on these enzymes in the food science arena. There's quite a bit on the top three, and it was a couple of food science sources that reported the off-flavors from cooking at 50C (presumably from cathepsin). The MC crew has recommended pre-cooking at 45C, but they don't explain their reasoning. They may just be splitting the difference between the active temperatures of calpain and cathespin. And they don't discuss the possibility of flavor development during aging. The most interesting paper I found is on aminopesidases. It finds that that these enzymes break down the products of calpains and cathespins into smaller, more flavorful molecules. I found a bunch of non-food science papers on these various aminopepsidases; they give the temperature ranges I cited above. I decided to go with a pre-cook of 40°C in order to 1) reduce the potentially bad flavor products from cathespin, which is most active at 50C, and 2) to avoid overheating alanyl and arginyl aminopeptidases and aminopepsidase C, and 3) to maximize the effects of calpain. This is a completely amateur hypothesis at this point. But I can say with 100% non-scientific enthusiasm that these ribs that were pre-cooked at 40°C were amazing. There was no control group (if I'd been more ambitious than hungry it would have been easy to do two groups of ribs; one with and one without the precook, and everything else equal). Beware of the dangers of these precooks. The enzymes in question thrive at the same temperatures as all varieties of pathogens and spoilage bacteria. I recommend pre-searing and / or blanching in the sous-vide bag, and keeping the time in this temperature range under 4 hours. I only have one circulator, so considering the time it would take to bring the water from 40C to 60C, I limited the pre-cook to 3.5 hours. -

NEEDED: Vegan Baking Advice for a skeptical pastry chef

paulraphael replied to a topic in Pastry & Baking

The biggest issue for me is the flavor of butter. It only comes from butter. So if you replace that, it better be with something that's delicious in its own right, and not just a flavorless oil, or worse, fake butter that tastes like microwave popcorn. Eggs aren't as big a problem. In much of pastry they're used for structure / texture, not flavor. To be blunt, they're an additive. Chefs have discovered myriad ways to get just about any texture you can imagine, with ingredients that typically work at much lower concentrations than egg protein, and that mask flavors less. I prefer ice cream made without eggs, or with a couple of yolks per quart, over traditional French ones with 6 or 8 yolks per quart. Hydrocolloids make up the difference, and do so without any disadvantages. (Not to suggest that this is vegan. I'm not giving up the milk ... ) -

[Modernist Cuisine] Sous vide tenderizing stage and enzymatic activity

paulraphael replied to a topic in Cooking

I've looked at a bunch of research on this. Partly I was trying to see if anything could enhance aged flavors and not just tenderness. I found some reports that pre-cooking at 50C can produce off-flavors. This correlates with the peak activity of a tenderizing enzyme called cathespin. Here's a summary of what I found. The question marks mean I had to interpret research papers that were trying to answer unrelated questions. I'm not a biologist, so please don't consider this the final word on anything. Tenderizing enzymes: Calpain most active: 40°C / 104°F Cathepsin most active: 50°C / 122°F (may introduce off-flavors) Collagenase most active: 60°C / 140°F Flavor-molecule producing enzymes: Aminopeptidases C, H, and P C: maximum 40°C? H: maximum 60-70°C? P: maximum 80°C? alanyl and arginyl aminopeptidases (RAP) stable up to 45°C? most active -1°C to 19°C? -

There are tradeoffs with different cooking times. It's a great benefit to be able to pasteurize, for example, but you'll dry out the meat much more than if just cooking to temp. For 1-1/4" burgers to get to medium-rare in a water bath set 1°C above the desired temp, cooking time is about 50 minutes. Pasteurization takes an additional hour and 20 minutes, during which time you lose a lot of juice.

-

NEEDED: Vegan Baking Advice for a skeptical pastry chef

paulraphael replied to a topic in Pastry & Baking

I'm of two minds about this. Part of me, when hearing the words "vegan pastry," wants to turn red, breathe fire, and scream "Get Out." Just on general principle. Another part sees how modern ingredients and techniques have allowed viable substitutes (and in many cases improvements) on many sacred cows. I haven't experimented with these in pastry, but there's probably a lot of knowledge out there. The few times I've been tricked into eating vegan pastry I haven't been impressed. This doesn't speak to what's possible. -

[Modernist Cuisine] Sous vide tenderizing stage and enzymatic activity

paulraphael replied to a topic in Cooking

I just made SV'd short ribs for the first time, and holy wow did they exceed my expectations. I thought this was going to take a few trials to get right. When I warm up the rest of them I'll try to take some pics. The ribs are pink, juicy, and fork-tender. I didn't use a knife on them at all. the meat fell off the bone when I unbagged them, but held its shape and could be cut into little blocks. The meat itself was pedestrian stuff from the local supermarket ... black canyon angus, which seems a couple of notches up from bargain basement. It was $6-something a pound in NYC. I browned them lightly, packaged in ziplocks with the deglazing liquid and a bit of stock, and then blanched each bag for a minute in simmering water. Then I pre-cooked in a 40°C/104°F water bath for 3.5 hours to speed up enzymatic reactions, and then turned up to 60C/140F for the remainder of the 72 hours. I made sauce from a beef coulis, which was made from ground shin meat and browned bones and mirepoix vegetables sous-vided with some beef stock, thickened with a bit of xanthan and lambda carrageenan (the stock was pressure cooked from roasted oxtail and ground shin and chuck and all the usual other stuff). The sauce had reduced red wine and shallots, porcini mushrooms, a bit of port, and thyme and rosemary. I cooked pearl onions on the side, sv. with a little beef stock. This is only one trial, so no way to say for sure. I think the pre-cook at 40°C does a lot of tenderizing, and may even enhance flavors. Many of the relevant enzymes become inactive above 40 or 45C. -

When I cooked burgers in a 56C bath and finished on a friend's gas grill, they didn't look raw inside. Just a nice medium rare. The grill took a while to brown them, so they ended up with a temperature gradient. But it was more like medium-rare to medium-well (with very little of the latter. There still wasn't any dry, gray meat anywhere. They looked really great. Some of the pictures I see surprise me; people will say they cooked at 55C, but the meat looks horror-movie red. I wonder if this is a photography issue and not a cooking one.

-

Hmmm, I haven't experienced this. The only thing I've noticed is that I could get away with salting the meat before grinding when cooking conventionally, but not when cooking s.v. ... the salt would lead to a firmer, overly cohesive texture for my tastes. Are you using a vacuum machine?

-

I don't know about shellfish in the shell, but try scallops in 50C/122F bath for 30 to 90 minutes (depending on size). lightly brine first and sear afterwards.

-

Blanching before sautéing is a restaurant technique. It's not required, and it's more work than cooking in one step, but it off-loads the work from service to prep. In general there is unlimited time for prep, but at service everything hits the fan at once, and so the fewer steps (and the less attention required for each one) the better. Having your greens properly blanched and the colors "set" means you can sauté and season at the last minute, quickly, and with very little to worry about. These techniques also work well for dinner parties ... another situation where it helps to cut down on things to do at service. You may not be cooking a la carte for 200 people, but you probably want to hurry up and join the party, and if you're doing it right you already have a glass of wine in one hand.

-

Rotus, I've thought about that. I suspect it would work well, but hasn't been my first choice, since it's usually sold at boutique butchers and farmer's markets and is priced higher than what I usually put in stock. But it may be worth considering for ecological reasons. I'd still have to pick a cut.

-

I just made my first batch using new methods (pressure cooked stock, sous-vide jus). I'm sold on the method and am now back to tweaking the flavors. I made the stock with a combination of roasted oxtail and ground shin meat, and then the jus/coulis more ground shin meat, and some browned chuck (a piece of 7-bone steak I had in the fridge) The result is good, but the flavor is a roasted beefiness that emphasizes the deeper, darker beef flavors. I'm interested in balancing things a bit. Maybe I can do a bit with aromatics (I didn't put any celery in this batch ... a bit might help). But I'm also interested in other beef cuts for the jus. Any thoughts on what cuts might emphasize brighter, grassier, iron-y kinds of flavors? Helpful if they're also relatively lean, cheap, and available. I'm open to other ways of balancing the flavors as well. Edited to add: I didn't get a chance to experiment with cheeks. How would you describe the flavor?

-

The issues you could conceivably face with long pasteurization time are with bacterial toxins (which can be heat tolerant) and with spoilage bacteria (which are much less understood than pathogens). Suppose, for example, you had rolled meat to a cylinder several inches thick, and there were portions from the outside that would take 6 hours to pasteurize. Those could easily spend enough time in a high-growth temperature range to create nasty stuff. There are some threads about noxious green goo in sous-vide bags, which is probably the result of spoilage bacteria. I haven't heard of pathogenic toxins building up in this situation. But it could happen. I can't see the scale of the roll you made. I'm guessing it's around 3" diameter, which is perfectly safe. Much bigger and you could be inviting problems.

-

It should. I calculated with SV Dash that a 3" diameter cylinder would pasteurize at that temperature in 3 hours, 20 minutes. At 3.5", you start getting into times greater than 4 hours.

-

I'm questioning the tool and procedure, not the ingredient.

-

I'm no expert on paella, but I'm suspicious of definitions that depend on a particular tool or procedure. For years traditionalists like Marcella Hazan said that risotto was only possible if one followed a very strict set of procedures in an open pan with constant stirring. Now almost everyone who's tried it in a pressure cooker has kept doing so, including some prominent Italian chefs. We've come to our senses and defined risotto by the result, not by what the wizard is doing behind the curtain.