-

Posts

5,175 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Store

Help Articles

Everything posted by paulraphael

-

@Btbyrd, my mind is a little blown that the ChefSteps recipe isn't full of typos. 100g of fructose in that formula would give the equivalent sweetness of 30% sugar, before even accounting for the sugar in the berries! and 50g of bitters? That's like 500 cocktails worth ... This isn't a prank?

-

Yeah, it's important to find food-grade dry ice. I've wished for a stronger carbonation effect (champagne sorbet was an application for this). I've found the carbonation disappears pretty quickly.

-

I haven't had the best luck with strawberries this season either. I've used Driscols (first from Mexico, then California) and then ones from the local farmer's market (mostly New Jersey and Long Island). The local berries haven't been better than the Californian, but to be fair I haven't tried in the last two weeks. I've measured the berries with a brix hydrometer at 8 to 9 (which translates to fair-to-middling). These have still made some pretty good strawberry ice creams and sorbets. I've come up with formulas that use a ton of fruit ... 40% in the ice cream, 75% in the sorbet. I compensate for the lower brix readings with some added sugar, but still go for lower sweetness than commercial ice cream. The biggest issue is that the bitter background flavor you sometimes get from less sweet strawberries is pretty pronounced. Not enough that I find it unpleasant, but it definitely gets your attention.

-

We've been eating Beyond Burgers every couple of weeks or so, and I have to admit they're pretty good. I'd say they taste better than the average burger at a an average burger joint (which is a pretty low bar). They're nowhere near as good as the burgers I make when trying to make a great burger ... which involves sourcing three different cuts of beef, grinding them shortly before cooking, and weighing the seasonings with a milligram scale. But they're much easier than that, and cheaper (price is coming down monthly), and no steer was harmed in the making of dinner. We're not eating these to stop climate change, exactly. We're doing it to get used to the changes that will be forced by climate change, or by any real response to it. I hate to break it to you, but we're going to be eating bugs, people. I have climate scientists among my friends, and all say that the disaster we're embroiled in is being massively underreported. We've got eleven years to create a carbon-neutral civilization ... that or we'll be depending on miracles. A few of us privileged folks turning vegan or driving Priuses or signing internet petitions isn't going to change much (people have been at it for decades now). If you really want to save the world, you have to force the hand of governments. I just joined Extinction Rebellion to throw some of my resources at the problem. I'd suggest doing the same, or finding another direct-action organization with a good track record. Also, worcestershire sauce is a nice addition to the fake beef.

-

This kind of thing is always interesting. If they succeed, that's interesting. If they fail, so is that. Whatever they learn along the way is guaranteed to be interesting. The fact that we know so little about what's in most fermented+distilled+aged foods is fascinating in and of itself. I like that there's mystery there. That doesn't mean I'm opposed to attempts at solving the mysteries, or finding more efficient ways to duplicate results. On another note, when I saw the photo attached to the Economist article, I thought it was going to be about something else: vacuum distillation. This, I'm convinced, will be a new frontier. When it takes off, we will taste whiskeys and brandies with flavors like we've never experienced.

-

Using commercial stabilizer in home made ice cream

paulraphael replied to a topic in Pastry & Baking

I'm just suggesting that you can get the exact same results with simpler, faster, more predictable methods. I understand that people like these recipes, but this doesn't confirm the analysis of why the recipes give the results that they do. Nor does it confirm that the given method is the only way (or the most efficient way) to achieve those results. With very high-fat, high solids recipes that include lots of egg yolk, you really don't need any special processing to get Ruben-esque textures. You've got very little water to control, and tons of stabilization and emulsification from egg proteins. If you like this style of ice cream, almost anything you do will give technically good results. -

Using commercial stabilizer in home made ice cream

paulraphael replied to a topic in Pastry & Baking

What stabilizer are you using? -

Using commercial stabilizer in home made ice cream

paulraphael replied to a topic in Pastry & Baking

That's just about increasing the solids content of the ice cream. Doing it by evaporation is a really inefficient, roundabout, imprecise way to do it. Every time I read about that approach I do a bit of a face-palm. It's much simpler and more precise to just add more skim milk powder. The granular texture doesn't sound like overcooked custard to me. That gives more of a pieces-of-scrambled-eggs texture. Graininess can be lactose or whey coming out of solution and making crystals. This isn't too common in homemade ice cream and I'm not sure what would cause it for you. And stabilizers actually work to prevent these problems. Did you post your recipe? -

Using commercial stabilizer in home made ice cream

paulraphael replied to a topic in Pastry & Baking

You can do much better than Haagen Dazs chocolate! I promise. Unless 23&Me says you have a genetically determined proclivity for very mild milk chocolate. -

I keep coming back to the press pot. It's out of fashion right now in the specialty coffee world ... everyone's all about pour-overs, which just don't excite me as much. The current obsession is with a "clean cup." But I like the sink-your-teeth-into-it full-bodied cup from the press. It doesn't taste unclean to me. I strongly recommend that anyone trying to dial in their recipe should use a scale. Just like with everything else in the kitchen. Think in terms of ratios / percentages. And use a thermometer. Water temperature matters. And of course a decent burr grinder. I don't think you need a great grinder, as you do for espresso. The tech support guy at Baratza reused to upsell me when my 10 year-old burr grinder died. He said that for coarse grinds, my ancient entry-level grinder would be as good as their higher end ones, so he just sold me the $5 replacement part. I agree with Mitch that the goal is well-balanced coffee. When people say they it "strong," I think it's an image thing. When coffee is too strong, the result isn't something bolder or more aggrandizing. You get some more bitterness, and counterintuitively, many of the subtler aromas and fruit flavors get masked. It ends being a flatter, less flavorful cup. It's best to brew a correctly balanced pot of coffee. Then, if your preference is for something weaker, add some water. Sometimes just a little bit will make all the difference ... almost like dribbling water into scotch.

-

The only question I have is how to guarantee the cocoa butter goes into an emulsion with the water. The proportions are way off from a ganache, and even with a ganache it takes some care to guarantee it won't separate. I'd be surprised if the emulsifying power of the milk proteins would be enough. Maybe a small amount of lecithin would help. There's plenty of good quality milk powder available, at least in the US. Organic Valley is decent; Now brand is excellent. You have to keep it fresh, because it takes on stale flavors. I keep mine sealed up in the freezer. Just make sure it's 100% skim milk. I doubt any subtle differences (like between low temperature and high temperature spray drying) would be detectable through the chocolate.

-

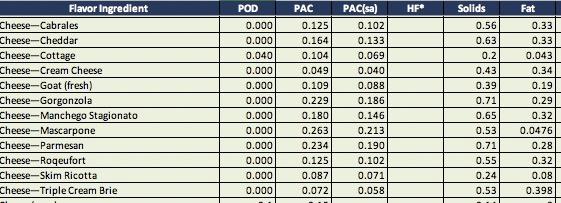

JBB uses cream cheese as a source of milk solids and stabilizers. It's an everyday-ingredient-friendly way to add both. Cream cheese has a high concentration of milk solids (which include both proteins and lactose, each of which is important to getting good texture in ice cream) and gums (xanthan, locust bean, guar) which can also improve texture and reduce iciness. You'll have more control if you add skim milk powder and a stabilizer blend separately. If the recipe froze hard as a rock, that's an overall formulation issue. My guess is that JBB wants to keep things simple and so doesn't include alternate sugars, like invert syrup and dextrose. If you stick with plain old table sugar, you have to choose between too sweet and too hard (at normal serving temperatures). She chose too hard, which I think is smart. You can always let it warm up longer, but there's nothing you can do about too sweet. "A touch too rich." You're being diplomatic. Many of those recipes are exercises in cramming as much milk fat and milk solids into an ice cream as possible. Some people like this approach. It certainly makes it easy to get a smooth texture (the only science behind this is that the formulas have very little water ... it's all displaced by fat and non-fat solids). But there are more elegant approaches to smooth texture, that let you get the mouthfeel you want with whatever fat level is most appropriate for each flavor. JBB's approach (in her factory) is much more nuanced. Her home recipes are maybe a bit doo simplified. Edited to add: I reread your post and saw that it was rock-hard at -19C. Almost every formula will be too hard at that temp. If you get a nice scoopable consistency between -12 and -14 you're in the normal range for professional ice cream. In Italy they often serve closer to -10. Sometimes this means it's formulated differently, but it often means it's just served softer. Re-edited to add ... if you're using enough cream cheese (or other cheese) to be a flavor ingredient, then Teo's spot-on ... you have to just calculate for it. Here's my data. I haven't tested this, so caveat emptor.

-

Using commercial stabilizer in home made ice cream

paulraphael replied to a topic in Pastry & Baking

Traditional home Philly-style needs help if it's to have a prayer of being smooth. At the very least it needs a whole lot of added milk solids, and should be cooked just like custard-based ice creams. Ideally it should have some stabilizers also. Hardness is variable; that's controlled mostly by the quantity and types of sugars. -

Using commercial stabilizer in home made ice cream

paulraphael replied to a topic in Pastry & Baking

Ah, I didn't realize you're designing recipes for special circumstances. That's a whole 'nuther topic. I had a consulting client with an ice cream shop whose dipping cabinet would't get colder than -10. We designed all his recipes to compensate. Unfortunately he then got the thing fixed and we had reformulate everything. -

Using commercial stabilizer in home made ice cream

paulraphael replied to a topic in Pastry & Baking

If you're warming your ice cream to -9°C, then it makes sense that it's fine. My software estimates 76% ice fraction at that temperature which is just slightly high for scooping. But most home freezers are below -16, and standard temperature for a scooping cabinet is -12 to -14. So right out of the freezer that formula would likely be cement-like. Here's the breakdown: Total Fat: 21.9% (very, very high.) Milk Fat: 17.9% (pretty damn high) Total Solids: 42.7% (upper end of good for a full-bodied ice cream) Milk Solids Nonfat: 4.7% (too low. even with this much fat, you'd want at least 8% to help control the unfrozen water) Stabilizer/Water: 0.08% (too low to have a noticeable effect) Egg Lecithin: 1.37% (very high. 10X the minimum. high lecithin isn't a problem, except that it can impede whipping. But I imagine this tastes like an omelet) POD: 118 / 1000g (bottom end of normal. I like this. Kids probably don't) Absolute PAC: 286 / 1000g (very low) My advice is less cream, less egg (unless you want to taste egg custard prominently) and then get your milk solids in there. The biggest difference between pro and amateur formulas is the milk solids. They give body, and work wonders for smoothness. Lactose has impressive water control powers, and the whey proteins add emulsification and a bit of stabilization when cooked properly. And milk solids don't mute flavors aggressively as milk fat and egg fat does. Then if you want to play with stabilizers, a good starting point would be around 0.15% by weight, or 0.25% by water weight (this if for DIY blends ... if you use a commercial blend, the instructions probably say to use more, because they usually include emulsifiers and also neutral bulk ingredients). -

Looking for a better way to save, organize, and use recipes?

paulraphael replied to a topic in Kitchen Consumer

A product like this might interest me if it ticked all of these boxes: -User has 100% control of their data. Data is stored in (or can be exported to) an open standard format, like xml. -Needs to be extremely friendly to recipes in which all ingredients are either by weight (metric) or percentage, or ratio. -If it even indulges volume measurements, it should offer a feature to automatically convert to weights. -Version control! Version control! Version control! -Can't be dependent on the device. Data needs to be accessible through cloud synching and available on a laptop or phone browser. -There should be plenty of sharing options with people who don't have the device / service. -

Using commercial stabilizer in home made ice cream

paulraphael replied to a topic in Pastry & Baking

It's mostly about convenience. There are actually some advantages to ice cream that's too hard. It means it will be warmer when it softens enough, so flavor will be a bit more vibrant. And it means that at freezer temperatures, there will be a higher percentage of frozen water, so there will less water activity overall ... and so less tendency for ice crystals to grow and agglomerate. But yeah, much of my childhood trauma comes from watching helplessly as my mom nearly set the Haagen Dazs on fire in the microwave. Night after night. -

Using commercial stabilizer in home made ice cream

paulraphael replied to a topic in Pastry & Baking

I suspect with that all that egg yolk and such a small quantity of stabilizer, the stabilizer won't make much noticeable difference. There's a lot of stabilizing coming from that thick custard. This recipe will be pretty hard to scoop at normal serving temperatures ... I like that it's not very sweet, but there's nothing picking up the slack for freezing point depression. -

I've bought Tellicherry peppercorns from a few different sources on Amazon over the years at pretty good prices. They've ranged from good to amazing. The best ones have a really 3-d flavor with all kinds of floral notes. They're less piquant than ordinary pepper. My understanding is that Tellicherry doesn't really signify anything about the variety or origin of the pepper ... it just refers to the size of the peppercorns (big). This may be one factor accounting for the variable quality. I'll try Penzy's next time, since they have a store in NYC. I'm a bit wary both of their prices and their practice of leaving spices uncovered in bulk bins. But the quality may be there.

-

Unless your love of these is primarily esthetic, I'd advise against buying the set. Maaaaybe get a saucepan or two. Those won't get preheated on hight heat, so you'll be unlikely to melt off the tin. You'll benefit from the precise temperature control. A little bit ... I have copper saucepans and clad aluminum / stainless saucepans, and in practice the difference is utterly unimportant. They won't make you a better cook. The skillet / sautée pans are a bad idea. Pans like this need to be preheated on high heat. I heat all my pans (except my one lonely teflon pan) to temperatures that would turn the lining into a shiny puddle. Searing food properly makes this a necessity much of the time. Also: the brass handles are highly conductive. The only reason anyone puts brass handles on a pan is that they're pretty. They're not the smartest idea. The roasting pan is just a colossal waste of money. You don't need any of the qualities of copper in a roasting pan. Least of all the price and weight. Generally, there are no sets of anything that are a good value. Different materials serve different purposes. If you do want copper saucepans for their performance characteristics, there's more utility in stainless-clad copper. The three brands are Mauviel (France) Bougeat (France) and Falk (Belgium). Falk makes the laminated material for all these companies, so the performance is identical for all, as long as your remember to get the 2.5mm thickness. Falk is also the least expensive (but often the hardest to find).

-

How long do your sorbets stick around after you make them? One thing we can also generalize about enzymes is that their activity slows in the cold. If your sorbets all get eaten within a couple of days, it seems less likely that enzymatic breakdown would be minimal. I don't think this is a case where a highly scientific test is necessary. You could make a couple of sorbets with fresh fruits known to have high enzyme activity, one batch with inulin and one without. Compare. Then store them for several days and compare again. You won't know if, say, 15% of the inulin has been broken down, but you'll know if it's still good, and if there's still a pronounced difference between the two versions.

-

Using commercial stabilizer in home made ice cream

paulraphael replied to a topic in Pastry & Baking

Can you post a typical recipe (in grams)? And figure out the temperature of the freezer? An easy way is to put a bottle of booze or rubbing alcohol in the freezer for at least 24 hours, and then get a reading with a good thermometer. It sounds like your freezer is cold (which is good ... it will harden the ice cream quickly) and that your formula might not have adequate freezing point depression (so it gets hard as a rock at freezer temp). Ideal freezer temperatures are always quite a bit lower than ideal serving temperatures. So you shouldn't expect ice cream to be easy to scoop without sitting out or in the fridge for a while. But if it's hard as concrete, you probably need to fix the formula. Another test is to let the ice cream sit out until it's a good temperature for scooping. It should be scoopable at -14°C, and easy to eat by -12°C. Stabilizers don't have any effect on freezing point depression. And it would be strange if your freezers defrost cycle were so radical as to cause the problems you describe. -

I think you're right that it's folly to try to accurately model something as complex and full of emergent properties as ice cream. But I find it's quite possible to produce useful models. For example, if my model tells me that a certain change in sugar balance is going to increase sweetness by 10% ... but the actual effect is an increase of 12% ... this may still be useful to me, even if it's not strictly accurate. It probably gets me closer than an educated guess would have, and so it saves me a round (or two or three) of trial and error. If, on the other hand, the sweetness went in the opposite direction, or if it went up by 80% ... then you could argue that the model is worse than nothing. As it happens, over the last few months I've been building models to help formulate ice creams and sorbets . Usually my experience resembles the first example. It gets me really close. Occasionally, it's way off. This is educational; it helps me fix the model. Predicting sweetness has been pretty easy. While research shows wide variances in perceived sweetness across different concentrations and temperatures, it turns out that in ice creams we're not working with such wide ranges. And differences in sweetness of plus or minus a few % don't seem all that significant. I haven't found fat content to affect sweetness much. Acid content makes a big difference in other foods, but the range of acidities in ice creams is fairly low. Bitterness is another story. Ingredients like cocoa powder have a significant impact. There's a pretty simple solution; assign these ingredients a negative PAC value. Sounds a bit simplistic, but it really works! Freezing point depression is just chemistry and math. It turns out the math is about five times as hard as I'd imagined (i've had to consult with dairy PhDs on two continents to get my models working right) but once it's done it's done. Modeling the effects of hardening fats is more difficult, because as far as I can tell no one's done it before. I've started with some wild guesses and gradually am refining them (in another thread, Jo told me her pistachio ice cream wasn't doing what my model suggested. Valuable information. I realized I was overestimating the saturated fats in nut oils compared with cocoa butter). Your questions about enzymes and inulin are interesting. I found one study that explored the breakdown of inulin, but in response to ph and storage time. They found that after 2 weeks in storage, strawberry sorbet does exhibit breakdown of inulin into mono- and disaccharides. But not sooner. Otherwise, all I've been able to find is examples of fruits and inulin playing happily together, including commercial pineapple sorbets that use inulin. It's possible that the enzymes are deactivated by cooking. But it's also quite possible that these enzymes are just proteolytic and so don't bother polysaccharides. Clearly, "more research is warranted," to quote every scientist ever. But it seems pastry chefs have been using the stuff in combination with commercial stabilizers and every variety of fruit for some time now, and no one's complaining about weirdness. They seem to like it.

-

A couple of (non pro) reviews. https://www.amazingfoodmadeeasy.com/equipment/sous-vide-equipment/reviews/anova-precision-cooker-pro https://www.reddit.com/r/SousVideBBQ/comments/bm4s7r/i_tested_a_prototype_of_the_anova_pro/

-

That's interesting about the short vs. long chain inulins. None of the scientific sources I've looked at mention this overtly, nor do the places selling it in the US (it's one of these annoying ingredients that's sold as a fitness supplement, a health food, and sometimes also a culinary ingredient. So half the people selling it won't even understand your questions. My information seems to be on the short chain variety, which may be more common here. What adds to the complexity is that (according to one study) perceived sweetness drops radically with low dilutions. So what has 35% sucrose equivalent at high concentrations may only have 10% SE at low concentrations. I imagine that with standard usage being below 4%, even the sweet variety is behaving more like 10% SE. Also thanks again for the tip to search Italian sites. Searching for "Inulin Sorbet" turns up next to nothing. "Inulini Sorbeti" goes on for pages!