-

Posts

16,766 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Store

Help Articles

Everything posted by liuzhou

-

I just saw a recipe which started 'rub your thighs with the spice mixture'. Now I have to wash my pants!

-

Is it normal for Farmers Market produce to be barcoded where you are? It certainly isn't here.

-

-

Finally, the end. Full of additives and self loathing, I need to wash out my mouth. They 'kindly' supply a small (245ml) bottle of milk. UHT, of course. I ignore that and pour a nice inch or three of Laphroaig instead. The shock of the previous item will not be assuaged by cow juice. So that was my CNY journey through Chinese snacks. It won't be repeated. Happy Dragons.

- 34 replies

-

- 10

-

-

-

-

Penultimately, we reach the abysmal depths, snack depravity. These are known as 米果卷, 'rice fruit rolls'. Sounds innocent enough but beware! Demons lurk within. Buried in the small print is the appalling truth - 甜玉米味! Sweet c@rn flavour!! Pausing only to photograph the evidence for the prosecution, these go straight in the trash, back to where they crawled from the slime.

-

Then there are these Milk Cakes. In fact, they are labeled as 'Milk Flavour Milk Cakes'. Clearly aimed at children, these features the easiest 'join the dots puzzle' ever devised and a milk and cow sticker for wherever you stick stickers. The actual edibles are just churn shaped biscuits/cookies. Not particularly milky, but edible. 'Inoffensive' is as effusive I can get.

-

There is light at the end of the box! I knew these would be in there somewhere. Seaweed rice cakes. I've never understood the appeal. Dry, hard and flavourless, they turn up everywhere from CNY to weddings to funerals. Still, I do admire the skill at making seaweed tasteless. Also, according to the ingredients, they contain bonito. I think they mean a bonito once swam past the factory in 1962. The bag contains four smaller bags, each of which contains two 8cm / 2.5 inch diameter cakes. Cardboard.

-

Yes. Sounds like my local supermarkets. Chaos! Hotpots are a favourite at CNY. I'm a snake too, but I like them. For dinner!

-

I posted something similar a few posts back but if it wasn't for my teeth, I'd be all over these. Last time it was beef flavoured broad beans / fava beans. Now it's the real deal. Chilli roasted broad beans. What more is there to say other than to curse old teeth. Well one thing. The portion is a bit miserable (smaller bag than the beef ones). Probably bigger bags are available.

-

Then 伦蛋糕 (lún dàn gāo), ring cake - 巧克力味 (qiǎo kè lì wèi), chocolate flavour. Not pretty but the best thing I've tasted so far from this box. Really it's just a sponge cake with a good chocolate flavour despite, or because of having even more additives than the last item. Would I buy one? Probably not.

-

I got excited when I found this packet. Wasabi peas, I thought. No such luck. According to the pack they are just roasted peas with no flavouring mentioned. Unless, of course you look at the ingredient l list and find that 48% by volume of the ingredients are food additives. 15 of them. Food Additive Flavour Peas. Pass.

-

These rolls promise thick caramel milk with pure cocoa flavour. They don't deliver. The two 'heart cookies' as pictured and described on the box are notable for their absence from the actual contents. False advertising. The rolls taste exactly as I expected. Of bland, cheap pseudo-chocolate. Zero caramel flavour. Neither particularly pleasant or unpleasant. I could eat these. I'd never buy them.

-

可爱的泡芙 (kě ài de pào fú) Lovely Puffs 牛奶味 (niú nǎi wèi) - Milk Flavour Neither lovely or particularly milk flavoured.

-

Today, Friday 9th February 2024 is 除夕 (chú xī), Chinese New Year's Eve, probably the most important day of the holiday. Most shops will close around noon or shortly after and everyone will head home for 年夜饭 (nián yè fàn), literally 'year eve food', New Year's Eve dinner, also known as 团年饭 (tuán nián fàn), Reunion Dinner. Literally millions of people have spent this week travelling home for this meal with their families. It's forecast to be the largest migration of people in history, as it is the first such to be almost Covid free since 2019. So, what's for dinner? I've been looking through internet accounts of what people consider to be the essential New Year meal. Few agree; some are nonsensical. A large number of people describe what their family eat and assume everyone else is doing the same. It ain't necessarily so. However, there are a few commonalities. Chinese New Year is an orgy of superstition and most foods are chosen for their extremely tenuous links, mostly linguistic, to desirable material outcomes such as prosperity and success in the upcoming year. Fish is important. But the superstition is more so. Fish in Chinese is 鱼 (yú), a homophone of 余 (yú) meaning 'surplus' or 'extra'. So, by eating fish, you will have surplus food and/or money in the new year. Obviously. The fish, usually carp, is cooked (steamed) and served whole, symbolising family unity and harmony. The head and tail are left on representing a) the surplus will last from beginning to end b) the notion of finishing what you start being important. The fish is placed on the table with the head pointing to the eldest or most important guest and then we can eat. But not all of it! The fish is eaten over two days, doubling down on the 'surplus' theme. We have enough for tomorrow. We pick the flesh from the middle part of the fish with our chopsticks. When we reach the bones we mustn't flip the fish over or all our luck will tip out and be drowned. Then we come to chicken. Again steamed is most common. And again served whole. Chicken is 鸡 (jī). But 吉 is also jí, a near homophone (only the tone differs) meaning 'lucky'. So eating chicken will clearly bring luck! Today, people will have been making 饺子 (jiǎo zi), dumplings. These must be wrapped and ready to cook before midnight. Jiaozi is associated with 交 (jiāo) and 子 (zǐ), the former meaning 'deliver' and the latter, 'midnight'. So the dumplings must be delivered before then. 交 (jiāo) can also mean 'exchange' so reminds us that it is time to exchange the old for the new. The dumplings are also held to resemble ingots of gold and 角子 (jiǎo zi) is a monetary unit and coin, also representing wealth (despite the coin being worthless today). Indeed such a coin is often hidden in one of the dumplings bringing wealth to the lucky recipient providing they don't choke to death on it. Tangerines and orange are also a New Year fruit. They are 橙 (chéng). An exact homophone is 成 (chéng) meaning 'success'. Pomelo is 柚子 (yòu zi), the first character of which is both a near homophone of 有 (yǒu) meaning 'have' and an exact homophone of 又 (yòu) meaning 'again'. Eat a pomelo and you'll have food again! Other superstitions at New Year are associated with noodles (longevity) and spring rolls and many more. After dinner, everyone sits down to watch the New Year Gala, a god-awful annual variety show on communist party controlled television. Talentless drones line up to bore everyone year after year. It reminds me of the old regime swept away by the Beatles 60 years ago. I'm going to eat nothing particularly festive, then attempt to finish cataloguing my snack box in search of something edible. 新年快乐!

-

These are, I suppose, fairly normal. A sort of breadstick. In this case, "vegetable flavoured". According to the ingredients list, the vegetables in question include crab and chicken bones. Otherwise only scallions are listed. Alongside the usual chemistry set. For some reason, the 56g box contains three separate bags, each containing 18.666666666666... grams of sticks (?). They are crisp but taste stale and not the least bit vegetal. Not nice.

-

Still going through the snack selection box, I find these. Garlic Peas In fact, the peas and garlic slices are separate and accompanied by small balls crispy dough. Most strange. They have a strong but not unpleasant garlic flavour. At least, they're not sweet.

-

The idea that people eat the relevant animal on its New Year celebrations is a myth. For a start, of the 12 animals of the Chinese year cycle, one is mythical, two are illegal to eat and three unacceptable to most people. Mythical: Dragon Illegal to eat: Tiger, Monkey Unacceptable; Rat, Snake, Dog This weekend will be my 29th CNY in China and I have been served the same food every one of those years. The only one of the 12 to maybe appear regularly has been chicken but never to my knowledge rooster. I have eaten everything on the list except the dragon, tiger and monkey but not at CNY.

-

Still in slightly savoury territory, 海苔花生 (hǎi tái huā shēng), seaweed peanuts. These coated peanuts come in many guises, this one being nori. Unfortunately, somewhat marred by the over-sweet coating.

-

These are more to my liking. 蚕豆 (cán dòu), broad beans (Vicia faba) aka fava beans. These are beef flavoured. The beans are cooked then roasted with flavourings and a bucket of preservatives and the like. I used to eat them, but they aren't kind to my teeth. Oddly addictive. If I were to buy them now, I'd buy them in the supermarkets where they sell them freshly roasted without the overload of science lab supplies.

-

Next random snack. 超QQ嚼劲软糖 Super QQ Chewy Gummies - Cola Flavor. Predictably disgusting. Additives added to additives and dusted with sugar. Chewy maybe. Super? No. Binned.

-

Lard is often used in Chinese baking. Not always appropriately. I remember one particularly disgusting birthday cake which smelled of farmyard. Just recently they have discovered butter. Don't know if it'll catch on, though.

-

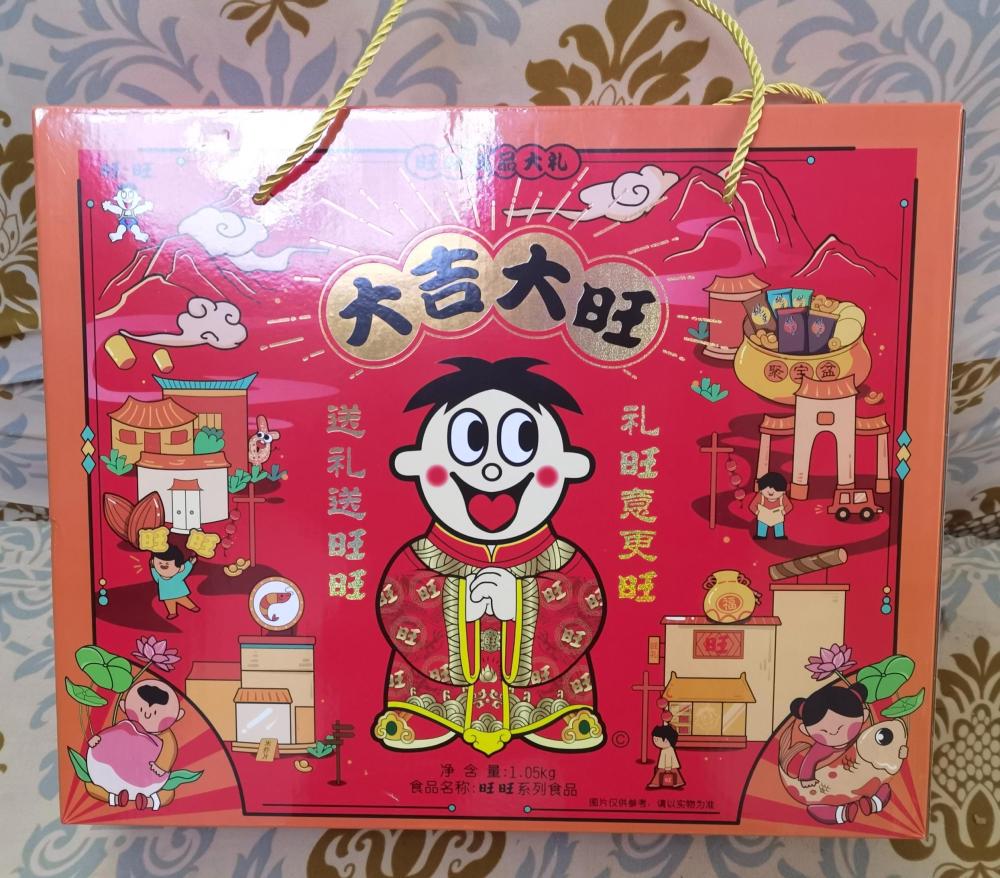

... and finally I come to the largest box. 大吉大旺 (dà jí dà wàng) means something like 'great luck; great prosperity' and is a typical CNY greeting. 旺旺集团 (wàng wàng jí tuán), Wang Wang Group Corporation is a Shanghai company, established in 1962, which makes and distributes all kinds of snack products, both sweet and savoury. This is their CNY selection box. I tip it out. I'll take these one by one at random. First up is these shrimp rice crackers. They're OK for the genre. Over salted and with that universal unidentifiable 'chip' flavour. Edible but I wouldn't go looking for them. More to come. Lots more.