-

Posts

16,813 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Store

Help Articles

Everything posted by liuzhou

-

One commenter on Chowhound said it all. "If it's cheap it's not saffron" Yes, Thanks. I am aware that a lot of 'saffron' isn't saffron. Some time back I was given a gift of 'Thai' spices which included 'saffron' and 'saffran'. One was saffron, the other was probably safflower.

-

-

A late addition to the dried tofu selection. This one is first stewed in 'spring-picked' tea, then dried.

-

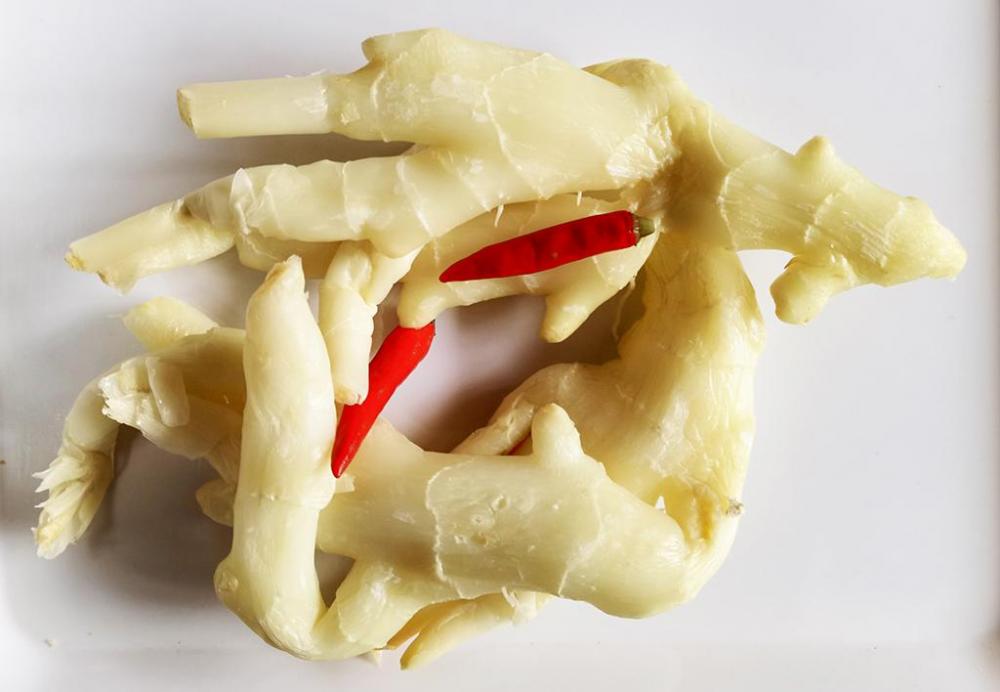

And here is a dish using all three of the holy trinity. Chickens' feet with pickled ginger, pickled chillies and pickled garlic. Enjoy!

-

Pig, new movie starring Nicholas Cage as a truffle hunter/ex-chef.

-

Actually, black vinegar is seldom used in pickles. White rice vinegar is by far the usual choice. I, too, love the flavour of the Zhengjiang vinegar and it's smokiness. Most black vinegar is made from a glutinous black rice. It is usually used with braised meats and fish. My friend J's husband does a wonderful chicken dish with it, but is protective of his recipe. She is going to divorce him as soon as she gets it! 😂 But most commonly, it is used for dips with dumplings etc..

-

Yes, there are recipes on that interweb thing which are ludicrously complicated. One recipe pushed by Goggle takes three days!

-

Thanks. Nothing easier. I use equal quantities of ginger and white granulated sugar. Some advocate freezing the ginger first to break down the fibres. I've never found this necessary, but I use young ginger. The ginger and sugar is simmered for about an hour. Exact timing varies, so just keep testing it for tenderness. I prefer to still have a bit of bite. When it's ready to your satisfaction, let it cool in the syrup, then sprinkle with dry sugar. Bung in fridge. I have no idea how long it lasts. Usually a couple of days around me! Keep the syrup. I use it in a seafood salad dressing with lime and orange juice, but that's a whole 'nother story.

-

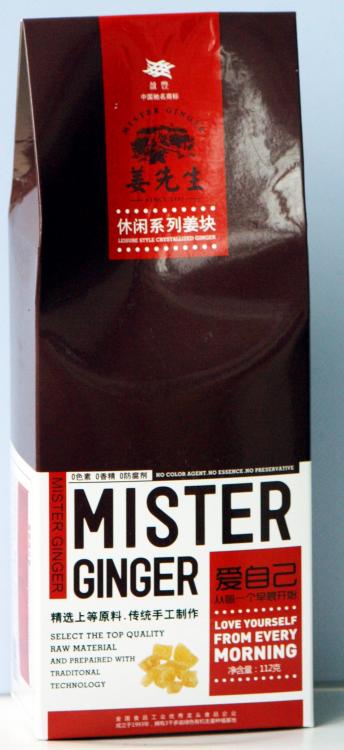

35. Preserved Ginger – 酸姜 (suān jiāng) - Pickled Ginger, 干姜 (gān jiāng) - Dried Ginger, plus I’ve mentioned preserved garlic; I’ve mentioned preserved chillies; so now it’s time to complete China’s holy trinity. First up, we have 酸姜 (suān jiāng), pickled ginger. I’ve only ever seen young ginger pickled. It is both home made and sold in markets, street stalls and supermarkets. I usually make my own. This is exactly the same as the pickled sliced ginger used in Japanese cuisine as a palate cleanser. Here is a commercial version. 嫩姜 (nèn jiāng) means 'tender ginger'. Then we have the dried ginger, (干姜 gān jiāng). This is used to make ginger tea, or powdered to make ginger soup. Ginger Soup Mix Finally we have crystalized ginger. I've only ever seen this once. but no worries, I make my own. liuzhou's home made crystalized ginger.

-

Yeah, thanks. Like @Anna N, I worked it out in the end. Hey! I hadn't had my first coffee!

-

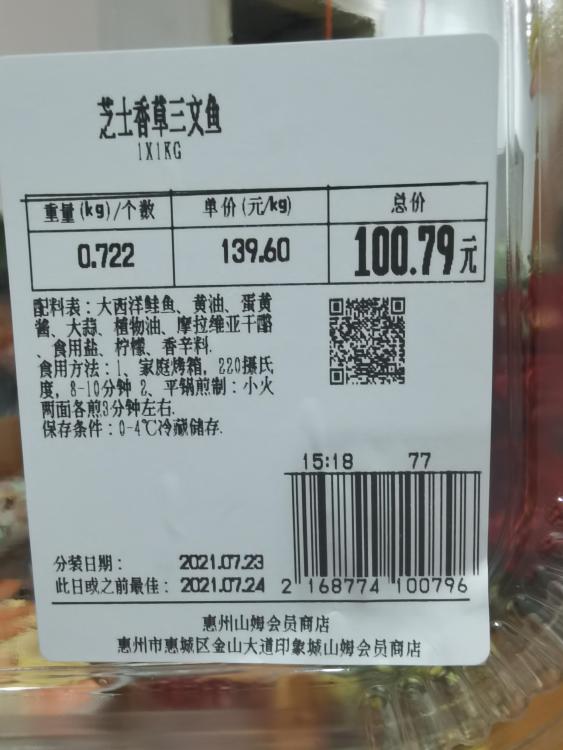

I just think this is weird. But first, I admire how, in Chinese dinner parties at home (or in a restaurant), no one thinks twice if offered a store-bought dish along with home cooked. This was a friend's food a few days ago. She has given her permission for me to post it here. I could make out that plastic box contains what I took to be salmon, some slices of lemon and what appears to be mayonnaise, but to be sure I asked her. She sent me the ingredients label, which fortunately she still had. This lists the ingredients as: Atlantic salmon, butter, mayonnnaise, garlic, vegetable oil, Moravian cheese, salt, lemon and spices. This is odd in itself. Moravianan cheese, I'm taking to be Olomoucké tvarůžky, the soft cheese from Loštice, Moravia, in the Czech Republic, rather than the Italian-sounding Gran Moravia, the hard cheese, also made in the Czech Republic, but using traditional Italian methods. But who knows? Not my friend. But what really spooks me is that it comes with clear instructions on how to cook the dish: Home oven: Bake for 8-10 minutes at 200℃; or pan fry on a low heat for about 3 minutes. Yet, there it is on the table, clearly uncooked. Of course, I asked my friend. "Oh! I didn't notice that! I thought it tasted a bit strange, but just guessed that is what foreign food is meant to taste like!" Full marks for being adventurous, zero for reading her own language. P.S. She teaches Chinese language in a high school!

- 399 replies

-

- 13

-

-

-

34. 干豆腐 (gān dòu fu) – Dried Tofu As well as fermenting tofu, it is also preserved by drying. 干豆腐 (gān dòu fu)* comes in many formats. Some are also flavoured by stewing with spices etc, first. Some are dried then smoked. Here are a few. Dried Tofu Layer Cake Dried Tofu Layer Cake Dried Tofu Shapes White Dried Tofu 豆腐卷 (dòu fu juǎn) Tofu Roll Tofu Roll Unwrapped 5-Spice Tofu Red Tofu "Noodles" White Tofu Noodles A Different Type of Rolled Tofu Smoked Tofu "White Chicken" Tofu Here in Liuzhou, a highly popular tofu iten is 腐竹 (fǔ zhú), which is made from the skin which forms on the top of the soy milk when being made into tofu. The layer of skin is lifted off and dried. Often it is rolled into sticks. Dried 腐竹 (fǔ zhú) Rehydrated 腐竹 (fǔ zhú) Fried 腐竹 (fǔ zhú) 腐竹 (fǔ zhú) is an essential part of Liuzhou's signature dish, 螺蛳粉 (luó sī fěn) or 'river snail rice noodles', but is also used in other dishes. 柳州螺蛳粉 (liǔ zhōu luó sī fěn) Lamb with 腐竹 (fǔ zhú) Tofu is also frozen, but this is not to preserve it. Freezing then thawing regular tofu makes it spongy, so ideal for soaking up sauces and hotpot flavours. * Sometimes the 干 (gān) meaning 'dried, is at the end - 豆腐干 (dòu fu gān). The meaning is the same.

-

It was very unusual for me; normally I'm a light breakfaster. But then, I'm not usually up at 5am either. Unless I'm on the way home from the night before, which wasn't the case this time.

-

5 a.m. Sunday morning. Sausage, Egg and Chips. Plus Tomato. Hunanese blood sausage, fried duck egg. I can cook in my sleep!

-

33. 腊八蒜 (là bā suàn) - Laba Garlic Laba Garlic @Tropicalseniormentioned these on her 'My Pickled Garlic Experiment' topic here. These jade green pickled garlic cloves are traditionally made for the Laba Festival – 腊八节 (là bā jié), held on the eighth day of the 12th month by the traditional Chinese solar-lunar calendar. Hence the Chinese name 腊八蒜 (là bā suàn), 蒜 (suàn) meaning 'garlic'. The preparation couldn’t be simpler. The garlic cloves are washed and put into jars with white rice vinegar (sugar can also be added according to preference), then left for around three weeks in a warm place. That’s it. The longer it is left, the greener it becomes. Laba Garlic in Jars Image Credits I have used these images from Wiikipedia, which I don't normally do, because I can't find any of the garlic now (wrong time of year) and I have no desire to make any just to take a photograph; not that I mind eating it. 1. Laba Garlic - Image by Dennis Wu6; This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic license. 2. Laba Garlic in Jars - Image by N509FZ; This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

-

32. 泡椒 (pào jiāo) – Pickled Chilli Peppers; 辣椒干 (là jiāo gān) – Dried Chilli Peppers When Peter Piper picked his peck of pickled peppers, he probably didn’t realise that a peck wouldn’t last a day in the average Sichuan or Hunan kitchen. Both provinces use copious amounts of both dried and pickled peppers, as do Guizhou and Northern Guangxi. These are often made at home but can also be found in every market and supermarket. My downstairs neighbour is drying these outside her apartment window right now. Sichuan Dried Peppers Dried "Pointing to Heaven" chillies - 指天椒 (zhǐ tiān jiāo) 米椒 (mǐ jiāo, literally 'rice peppers') drying in the sun. Pickled Peppers Pickled Red Chillies Pickled Small Green Peppers Commercially produced 小米椒 (xiǎo mǐ jiāo) - Pickled Small Rice Peppers Commercially produced 小米椒 (xiǎo mǐ jiāo) - Pickled Small Rice Peppers 灯笼椒 (dēng lóng jiāo) - Lantern Chilli (very hot!) 灯笼辣椒酱 (dēng lóng là jiāo jiàng) - Lantern Chilli Paste (very hot!) There are many more, to which I shall doubtless return.

-

That last blood sausage is always cooked, usually in dishes as shown in the video I linked to. The main Hunan condiment, if you call it that, is chilli. That said, those tofu and blood sausages contain minimal amounts of blood compared with most blood sausages around the world. I do not detect any metallic taste in any blood sausage, but that may differ for other people.

-

Fuchsia Dunlop's Land of Fish and Rice(eG-friendly Amazon.com link) has been published today in Chinese translation. This is the third of her books to be translated and published in China, following Shark's Fin and Sichuan Pepper: A Sweet-Sour Memoir of Eating in China (eG-friendly Amazon.com link) and The Food of Sichuan (eG-friendly Amazon.com link). A rare honour and a rare achievement.

.thumb.jpg.c08547c390f195cdce7097ccfc91391c.jpg)

.thumb.jpg.2693f82d41c47c3049d3023584275503.jpg)