川菜 (chuān cài) - Sichuan (四川) Cuisine Part One

After Cantonese, this is probably the most famous Chinese cuisine internationally, although until relatively recently, only a handful of its dishes appeared on most American or British Chinese restaurants menus. Mapo Tofu (actually 麻婆豆腐 (má pó dòu fǔ) in Sichuan – ‘tofu’ is the Japanese pronunciation) and Kung-po (or kungpao) Chinese (actually 宫保鸡丁 (gōng bǎo jī dīng) in Sichuan) were and are still the only Sichuan dishes on many menus. These non-Mandarin names can be attributed to the restaurants still being Cantonese.

Mapo Tofu

However, that is changing. When I left Britain in 1996, there were zero real Sichuanese restaurants anywhere in the country. Bar Shu opened at 28 Frith Street, Soho, London, W1D 5LF in 2006, near but significantly not in the Cantonese enclave that was Chinatown. Tel: (+44) 2072878822. They wanted to distinguish themselves, I guess. Fuchsia Dunlop consulted with the restaurant’s opening and menu.

Bar Shu Sichuan Restaurant, London

Her book 2019 The Food of Sichuan (eG-friendly Amazon.com link), a revised and expanded version of her original 2001 book, Sichuan Cookery (published as Land of Plenty in 2003 in the USA), is an excellent introduction to the cuisine and the culture behind it. Remember all these three are essentially the same book. Don’t do what one friend did and bought all three, thinking they were different. I suggest the 2019 version. It has even been translated into Chinese and is available here, an extremely rare honour.

Much as I recommend the book, I do have one issue with Ms Dunlop, though. In all her books, she gives the Chinese name for ingredients and dishes, but then gives the Pinyin transliteration without the tone marks which are essential for correct meaning and pronunciation in Chinese, making them useless. She also mixes Mandarin and Sichuan dialects without ever saying so. She even gives a few Vietnamese names without the essential diacritics; Vietnamese fish mint, she tells us is diep ca in Vietnamese – no; it’s diếp cá. This may seem pedantic but it’s essential in both languages. Not using them or getting them wrong can often change the meaning. My favourite example is shui jiao. Do you mean boiled jiaozi dumplings (水饺 - shuǐ jiǎo) or go to bed (睡觉 - shuì jiào) or several other possibilities?

Sichuanese restaurants had opened in the US slightly earlier, apparently following the publication of two cookbooks: Robert Delf’s 1974 The Good Food of Szechwan (eG-friendly Amazon.com link)* and Ellen Shrecker’s 1974 Mrs Chiang’s Szechwan (eG-friendly Amazon.com link).

* Few people in China, including Sichuan knows what Szechwan means; it was never pronounced that way in China. They’ll maybe guess you are speaking German or Polish for some unimaginable reason.

Today Sichuan restaurants are to be found in many of the world’s major cities, if not in the suburbs or smaller towns, yet. But it’s Sichuan food in Sichuan this is about.

Sichuan is normally all about big, bold, spicy flavours and these are achieved using some ingredients only introduced in the west recently, if at all. The stand out ingredients are, of course, Sichuan peppercorns, chilli and doubajiang, which I’ll take one by one.

花椒 (huā jiāo, literally ‘flower pepper’), Sichuan peppercorns, Zanthoxylum simulans, ain’t necessarily from Sichuan. They are often from neighbouring provinces such as Yunnan and Gansu and can be found in Nepal, but it is in Sichuan they are used most. There are two varieties – red and green. The first are much more common. The second are not unripe red ones, but from a different cultivar of Zanthoxylum. The Japanese sansho (actually 山椒- kona-zanshō), Zanthoxylum piperitum is a closely related cousin.

Red Sichuan Peppercorns

They are neither flowers or true peppers, but berries of the prickly ash tree. They have a citric and floral taste but their unique feature is that they impart an intense sense of numbness (麻 -má) in the mouth. This is known scientifically as paresthesia and is caused by a compound they contain called hydroxy-alpha-sanshool. The more? fresh the berries, the stronger the sensation.

The peppercorns should have had their seeds removed before sale, but a few may linger. They are unpleasant and sand-like. One well known food website which shall remain nameless, recommends using ground peppercorns which I recommend to people who have lost their sense of taste or like musty, stale flavours! They also say they keep for years, to which I say <censored>! I buy them in 50 gram / 1¾ oz bags and can easily tell the difference as I reach the end of the bag a week or two later. They lose potency quickly.

Sichuan peppercorn oil is widely used as a condiment. Also known as prickly ash oil, it holds the numbing for longer (but not forever). I occasionally sprinkle some over dishes or into hotpots.

The green variety, either 青花椒 (qīng huā jiāo) or 藤椒 (téng jiāo) are green Sichuan peppercorns, referred to in English as rattan vine peppers. These are even more numbing and citric, especially when fresh, the way I usually buy them, though that’s difficult to do outside the immediate area. In fact, they only became available in China recently. When I arrived they were unheard of.

Fresh Green Sichuan Peppercorns

Dried Green Sichuan Peppercorns

For 40 years, Sichuan peppercorns were banned from the US, supposedly due to concerns that they may carry a disease known as canker which attacks citrus trees. There was little, if anything to back up those fears. In 2005, the ban was lifted provided that the berries were heated to 60 ℃ / 140℉ for at least 10 minutes. Unfortunately, despite destroying the non-existent canker, this also negatively affected the flavour and numbing qualities. I understand the ban has now been totally lifted (?), but the Chinese producers didn’t get the e-mail and most still routinely carry on doing what they have been doing for the US market for almost 60 years.

In the US, Mala Market carries both varieties (dried only) at a price. The red can be found in most larger supermarkets in the UK, but the green are scarcer. Chinese supermarkets and Chinatowns may have.

Mention of Sichuan peppercorns naturally leads me on to 辣椒 (là jiāo), literally ‘hot peppers’, chilli peppers. Again not, not true peppers but the fruit of small trees, They were called peppers by the Spanish and Portuguese invaders as they tasted hot. Introduced from the Americas into China in the 16th or 17th centuries (reports vary, although the first written record is in 1617) by the Portuguese. They didn’t arrive to Sichuan until 1749 and were, even then, not taken up as food for a long time, but were thought of as ornamental plants.

China has hundreds of different chilli cultivars but Sichuan prefers 朝天椒 (cháo tiān jiāo, facing heaven chillies) aka 指天椒 (zhǐ tiān jiāo), ‘pointing to heaven chillies’. 七星椒 (qī xīng jiāo), 7 star chillies are also used. Guizhou chillies make a good substitute if you can find them, but Thai bird chillies do not. They are too hot and the flavour will be quite different. But possibly the most widely used chillies are 二荆条 (èr jīng tiáo) chillies, used fresh and dried and used in Sichuan’s favourite sauce below. Most chillies are used dried in Sichuan, although they also employ er jing tao make use of in their pickled form.

Fresh Facing Heaven Chiilies

Dried Facing Heaven Chillies

Dried Erjingtao Chillies - detail.1688.com

Together, Sichuan peppercorns and chilli make Sichuan’s near ubiquitous signature flavour, 麻辣 (má là) mala, with 麻 (má) meaning numb and 辣 (là) meaning hot: hot and numbing. The combination is used in literally hundreds, if not thousands of dishes.

Despite the reputation, Sichuan does not have China’s hottest food, as explained here. I suppose the reputation arises because Sichuan food is the hottest you are like to find in most restaurants outside China.

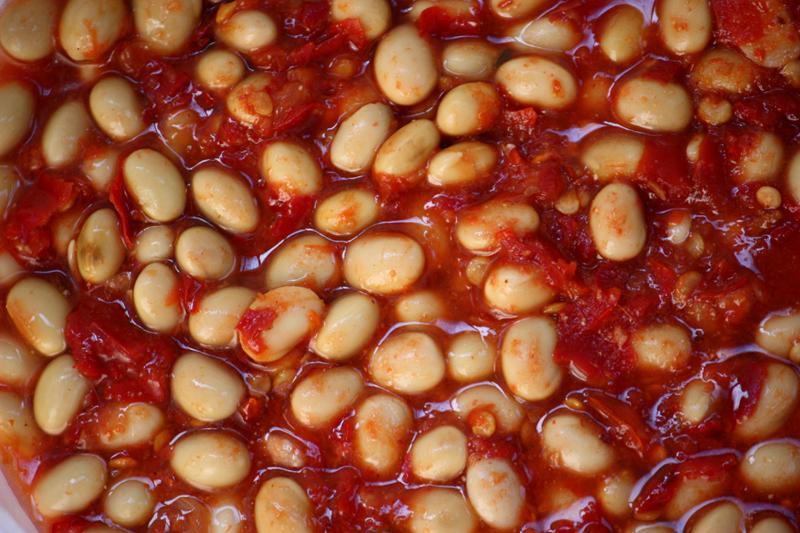

The third key ingredient is 豆瓣酱 (dòu bàn jiàng, literally ‘bean bits sauce’). This is a thick sauce made from broad beans aka fava beans, which are fermented with 二荆条 (èr jīng tiáo) chillies, salt, wheat flour and water. Known in America as tobanjiang, the sauce is pungent, spicy and salty.

Doubanjiang

The best is said to come from 郫县 (pí xiàn), a county just outside Sichuan's capital, 成都 (chéng dū) Chengdu. If you want the ‘authentic’ flavour of Sichuan, 郫县豆瓣酱 (pí xiàn dòu bàn jiàng) will be on the label. Beware of anything containing soy beans – these are cheap fakes. Also, the widely distributed Lee Kum Kee version is near universally rejected as being the worst of their numerous products – flat and the wrong flavour. Cantonese (LKK is Cantonese) and Taiwanese doubanjiang are not the same thing. Avoid them if it’s Sichuan you want to taste.

The sauce is best fermented in large jars under the sun for up to five years, being stirred frequently, but modern methods have reduced that time considerably. Aficionados still insist on the traditional method. Basically the darker it is, the longer it has been aged and developed flavour. These two brands are highly reputable and available overseas.

Dandan Doubanjiang

Juancheng Doubanjiang

A couple of other ingredients Ms Dunlop briefly mentions but doesn't give much detail on are:

山胡椒 (shān hú jiāo, literally ‘mountain pepper’) or 木姜子 (mù jiāng zǐ, literally ‘tree ginger seeds’) are Litsea seeds, Litsea cubeba (Lour.) Pers.). Not native to Sichuan, they are nevertheless used there, particularly in the south of the province. From Guizhou and western Hunan, the trees are a member of the laurel family and the seeds intensely citric in taste. The seeds are available, both fresh and dried, but most is made into litsea oil, used as a condiment. It is similar in taste to lemongrass.

Litsea seeds

Litsea Oil

If you search for it online you will be directed to dozens of sites proclaiming it the greatest thing ever, but not for food use. The wellness charlatans are leaping all over it when they need a rest from their vagina-scented candles.

The other ingredient is 保宁醋 (bǎo nìng cù), Baoning vinegar, as opposed to Zhenjiang (often Chinkiang in America) vinegar, the default choice in the rest of China, Baoning is the one Sichuan prefers. They must be locavores. This local black vinegar dates to the end of the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644). Unlike most Chinese vinegars which are made using rice as the main grain, Baoning uses wheat. It also includes many herbs in the preparation but these are strained out before you buy it. It can be aged from anywhere from 1 to 10 years – the longer the better and more expensive, of course.

Baoning Vinegar

Now you've got the main ingredients sorted out, it's time to look at some dishes. However, I am going to be busy the next week or two. So the next part of this may be delayed. I worked out this is the 21st cuisine I’ve written about (including sub-categories). Many more to come. Eight cuisines in China? Bah! Humbug!