-

Posts

162 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Store

Help Articles

Everything posted by Chris Ward

-

Interesting I've never heard of American meringue either but the recipe for Pavlova is like mine. We used to cook meringues during our afternoon breath from 3 to 5.

-

I have said - boasted, even - elsewhere that the only electrical device I use in a kitchen is a hand-held immersion blender. A cheap one, to boot, a €10 device bought from Lidl, Europe's favourite discount supermarket chain. This is a lie. I also have a hand-held mixer. For mixing cake mix and for whipping up meringues. But that's all. I have an excuse. A reason. A medical note, even, for straying from the hand-beaten path: carpal tunnel syndrome. 25 years typing on keyboards as a journalist followed by 7 years chopping, cutting and dicing ingredients in restaurant kitchens did for both my wrists. To the point, in fact, that I have permanently lost a sizeable portion of the use of both hands, even after corrective surgery, and am now declared officially Unfit For Kitchen Work by the Medecin de Travail, the work doctor whose word is law in France. It would actually be illegal for me to work as a professional restaurant cook now. This is all a long way round to say that I use a hand mixer to make meringues. Making meringues is the only time in my life when I wish I had a stand mixer, a big old Kenwood like my mother had for 20 years before giving it to me and which I wore out after another 10 years of use. And then I think about the other things I'd rather do with €500 and continue holding on to the hand mixer as it beats the meringue mix until my wrists simply can't take it any more. Yes, even holding an electric mixer is painful, which is why I wish I had a stand mixer. But, as the French say, you can't have your butter and the money for the butter so I spend that €500 on something more useful, like food for my children or books. Mostly books, actually. And foie gras. Meringues are not really difficult to make: you use the egg whites left over after making crème brulée, crème anglaise, crème pâtissière, crème whatever. You add 75g of sugar per egg white little by little as you beat the egg whites. That's it. Well, OK, there are a few points. First, when you've finished separating the whites from the yolks, making sure there's no yolk at all in the whites, put the whites in the fridge. Get them and the bowl you're going to beat them in nice and cold. Same as for whipping cream, cold is your friend. Put the beaters for your mixer in there too if you like, can't do any harm. Make sure everything is scrupulously clean. Then you'll have only yourself to blame when it doesn't work. Start beating the whites on the lowest speed to break them up a little, throwing in a couple of pinches of salt. For the 12 whites I used in this recipe, I put three decent three-finger pinches. When they've broken up, turn the speed up on high and start pouring in the sugar. I do this from the packet - the recipe calls for 75g of sugar per white so 12 x 75 = 900g. I put 100g into my vanilla sugar box and just poured the rest of the 1kg packet into the meringue mix bit by bit. So, this will make French meringue. It gets fairly stiff and will hold a medium peek, but as you can see in this picture they don't always hold up perfectly after piping them out: Some do, some don't. Your piping technique will also have an effect, but I'm getting ahead of myself here. If you want good, stiff peaks and meringues that hold their shape then you need to make Italian meringues, not French ones. The ingredients are the same except to make Italian meringues you need to heat the sugar to 115°C, which is quite hot. You slowly drizzle this hot sugar into your beaten egg whites as you keep stirring, which is hard to do if you don't have either a stand mixer or a third hand. Or a commis. I have a commis but she's 8 years old and I'm reluctant to let her near molten sugar. So, French meringue it is. As you can maybe see in the picture above, the meringue should take on a glossy sheen when it's getting towards being beaten enough. And, of course, when you lift the whisk up the mix should form a peak which holds its shape well. There are schools of thought about when to add the sugar - before, during, after or a combination thereof. Me, I get it going and then as the egg whites start to get their form I start drizzling in the sugar, slower or quicker depending on my mood and what's on the radio. The real secret to meringues, if there is one, is to beat them for MUCH longer than you think is necessary. Time yourself and see how long it takes to get them to the point where you think they're OK; now beat them for the same amount of time again. They'll get much stiffer. Me, I beat them until I can't bear to hold the mixer any longer and my 8-year-old commis has gone to make meringues in her Minecraft kitchen. And then you pipe them out onto a baking sheet or dollop them onto it with a big spoon You see giant dolloped-with-a-big-spoon meringues in many French patisseries being sold pretty cheaply, €1-€1.50 each as the patissiers try to get rid of their excess egg whites - most creams and crèmes are made with just egg yolks so there's always a surplus of whites. Which is why, incidentally, there's a wealth of patissiers around the Seine river in Paris: vintners importing wine by barge from Burgundy and Bordeaux into the capital used egg whites to clarify their wines, giving them an excess of egg yolks which were snapped up cheaply by medieval patissiers who set up shop near the river. Anyway, choose the form you like. The results go into the oven to dry, not bake - if they're coloured at all they're overcooked - at 80°C for 3-6 hours, depending on their size. Professional patissiers and restaurant kitchens have ovens with 'ouilles', vents you can open to let out moist air from the interior. Domestic ovens mostly don't, so I prop mine open half a centimetre or so with a folded tea towel. It helps the drying process go quicker. When I worked with Jean-Remi Joly he used to dust his perfectly identical baby meringues (served as mignardises with after dinner coffee) with chocolate or cinnamon powder. One day he tried dusting on the powder just before putting them in the oven and the resulting colour and taste were gorgeous, so I recommend trying that if you like such things. Otherwise you can mix in flavourings like strawberry coulis or pistachios when the mixture is fully beaten. I pipe the meringues onto greaseproof/silicon paper, which seems to be the easiest thing to unstick them from; you can test if a meringue is cooked sufficiently by trying to peel it off the paper - if it leaves its base on the paper it's not yet dry enough, keep cooking it.

-

Several people have asked for details on how to make this, so here we go. You need potatoes, lardons, onions, cream, milk, salt and pepper. And grated cheese. And butter. Slice up the onions fairly thinly – about 1-2mm slices. Put them in a pan with hot butter and the lardons and fry them off until the onions are transparent and the lardons cooked through. While this is cooking, slice your potatoes. I cut them 2mm thick using a mandoline (details on mandolines here – bonus chip recipe!) – be careful not to cut your fingers. You need enough potatoes sliced to roughly fill your chosen container – I use a Pyrex dish, something more rustic is fine. I don’t bother peeling the potatoes first because I’m lazy and the skin’s good for you. Put the potatoes in the dish, pour in enough cream and milk to almost cover them, put the lardons over the top and squish them into the crevices and in between the slices of potatoes. Cover with a piece of tin foil and pop into the oven at 180°C for an hour. Uncover and check the potatoes are cooked, then sprinkle over a couple of handfuls of grated cheese, then back into the oven for another 10 minutes. Finish it with a few minutes under the grill if you like it really crispy. A couple of notes: Yes, you can add garlic, either minced up with the onion or just cut a piece in half and wipe it around the inside of your baking dish. I don't do this because my young daughters find the taste too strong. Yes, you can add Reblochon cheese to the recipe. The problem with this is its price - the entire cost of the above version of the recipe is about €2; adding €12-15 worth of Reblochon changes the economics completely. No you can't add mushrooms. Mushrooms? Really? Actually you can add anything you want. Except white wine, as Felicity Cloake does in The Guardian. That's just wrong.

-

Thanks! Cooking gives both the cook and the victims pleasure - a double pleasure for the cook. Transmitting my love of cooking to my children was always one of my ambitions, and so far it seems to be working.

-

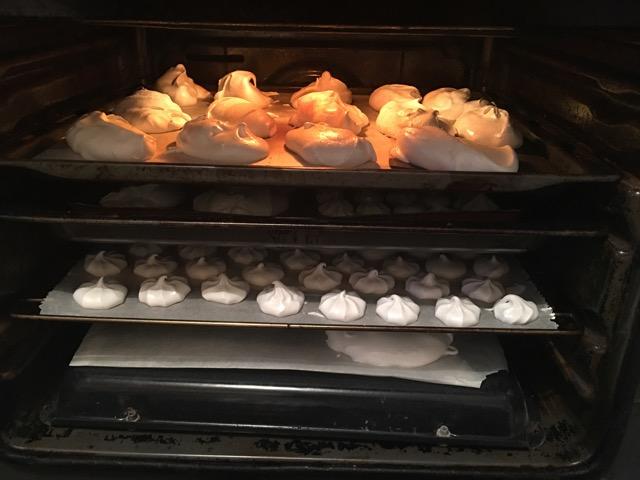

I hope that, when I'm even older and creakier, my daughters will continue their love of cooking. Right now at 6 and 8 they love cooking with Papa; we'll see if it continues, but it's a good start. First things first, write out your prep list. This is very important - work out what needs to be done first and so on. No point working on the meringues first since they take 4 or 5 hours to dry out in the oven so we put them in last, otherwise the oven's out of use while they do their stuff. We made the madeleines first, the full recipe - 9 eggs, 500g sugar mixed to the ribbon stage, 400g of softened butter, 400g flour, baking powder, the lot. We made dozens and dozens of them in the end. Three bags full in fact, as it were. Best part of baking is, of course, licking the bowl clean afterwards. Then we made brioches. Two of them, one smooth and one gnarly - someone in the house likes chunky crusts. Not me, I like a smooth crust. Then we made quiche. Two in fact. One with onions and bacon lardons, the second with tuna and sun-dried tomatoes. And Tartiflette and rosemary and thyme ciabbata. Tartiflette is very popular in our house, so we made two of them. And then we got to the meringues with the egg whites left over from making a dozen crème brulées - which I forgot to photograph, it's true. But hey, they're all the same. Ours were vanilla flavoured today as the lavender plants' flowers are over now. The little meringues piped ready to go into the oven to dry. The little 'blobs' on the sheet next to the meringues are drops of mixture under the baking paper to hold it down while I pipe the meringues themselves. Some of the larger ones at the top of the oven, and two giant ones lurking at the bottom. When you're 8 years old, the bigger the meringue the better. Unlike commercial ovens, my domestic oven doesn't have vents at the top you can open to let out the moist air, so I prop the door open slightly with a teatowel. Works fine. The finished baby meringues. They won't last long in our house. To round out the day we made 4 litres of yoghurt - 4 litres of milk, 4 small tubs of activated yoghurt, leave it in the warm oven (50°C) overnight. One litre gets strawberry syrup, one litre gets chocolate powder, and the final two litres are strained down to just one litre of thick Greek-style yoghurt to eat with honey for breakfast.

-

I've done it in every restaurant where I worked, yes.

-

Tartiflette today. Winter's coming, need to stock up on that body fat for the cold period. Wait, I already did that. Oh well, too late now.

- 480 replies

-

- 11

-

-

19: Big promotion, one of the proudest professional moments of my life If you have to take time off sick from a restaurant in the South of France, you’re supposed to do it in the winter when it’s closed anyway. Luckily for me it’s January and the restaurant is - mostly - closed for the whole month, only due to officially re-open on St Valentine’s Day. There are a few groups coming in though, tourists passing through and a few local societies having their annual dinner so we’re opening the restaurant for them. And, being a proper French restaurant, obviously we’re not hiring in anyone to do any work so all these groups are catered for by just Chef and me. This means I get to do lots of prep work before service and then work in the kitchen during service, as well as doing all the plonge, the washing up. It’s making for long days doing exactly what the doctor ordered me not to do - standing up. In fact, the doctor wanted me to go to hospital, this infection is so serious. Being a professional cook I, of course, refused, and visit a local nurse every morning to get injected in the stomach with antibiotics. And the effort is worth it because the great news is that, after Easter, Chef has promised to hire someone else as the full-time plongeur and he’s going to promote me to Chef de Partie des Entrées, the Starters cook. I feel very, very flattered indeed. He had been speaking over Christmas with my school chef and told me how impressed they both were with my progress at school and in the restaurant. Just before I became ill he sidled up to me - literally - and started talking about how I was doing at school, and wondered what I was thinking of doing when I passed my exam. “I suppose you’ll be looking around for a job as a Commis?” he asked. In fact, at this point my heart started to sink because I’d been hoping to stay on with him, even if it was just as plongeur. He has very high standards and I knew I was lucky to be allowed to work with him. So imagine how I was surprised when he said, “How would you like to work here - as Chef de Partie des Entrées?” This would be a big step-up for me, jumping right over the Commis level to become responsible for all the starters in the restaurant. Menu planning, designing dishes, the lot. Even more hard work and none of it easy. Of course I said “Yes”. But of course that’s a few months away and I can still eff up badly enough to get fired, let alone be promoted. So, knuckle down. School this week begins with cleaning and filleting rougets which we will be cooking this afternoon, and then on to making scrambled eggs the hard way and cute puff-pastry baskets. The hard way means cooking them over a bain-marie, same as doing a sauce hollandaise; in fact, Restaurant Chef has already taught me a much better method of doing things like this which need a bain marie according to the cook book – do them on the fourneau, that part of the cooker which I believe may be known as the ‘flat top’ in the US. Anyway. RC’s patented method for cooking stuff which mustn’t get too hot is to put it on the edge of the fourneau and keep a hand on one side of the pan; when you smell burning flesh, the pan’s too hot so move it away from the heat a little until the sizzling noise dies down (NB: This is a joke, don’t try this one at home. Probably.) It works, too, for hollandaise and scrambled eggs, although the breakfast staff who actually cook the scrambled eggs at the hotel aren’t too keen on the idea of singeing their flesh. Wimps. At school, of course, we have to do this Properly with a capital ‘P’, so bains-marie are mounted all over the kitchen as we set to. A Bain-Marie is a bowl set over a pan of barely-simmering hot water, so everything in the bowl is cooked at a maximum of 100 degrees C, and so it takes absolutely ages and ages to prepare eggs this way, I can’t imagine breakfast clients waiting this long, I think to myself as I stir and stir and stir, thinking of the faff if we had to do 48 covers this way. Still, as I’m learning today we have to do things the way they’re shown in our text book, not how you might think it’s better to do them in real life. The scrambled eggs go into the puff-pastry baskets we made with the pate feuilleté we produced first thing this morning – détrempe (mix flour and water in appropriate proportions) then refrigeration, then battering flat the butter so it’s one third the size of the pastry, and the first two folds; one third into the middle from the left, another third into the middle from the right, turn 90 degrees, refrigeration, rolling, two more folds, more refrigeration, more rolling, two more folds, yet more refrigeration, always in the same order. And then rolling it out to about a third of a centimetre thick and cutting out the baskets and folding over the corners…it’s harder to do than it is to describe and it’s impossible to describe. But my baskets rise nicely, thanks to the practice I’ve had back in the restaurant making puff pastry – although the marble counter top there does make it easier to keep the pastry cool, I have to say. We make a little fondu de tomates - tomatoes mondés, peeled and de-seeded, chopped up and reduced with a little onion and herbs over a low heat - to put on top of the scrambled eggs, giving us Paniers aux Oeufs Portuguese, which we send out to the self-service cafeteria for staff and students next door as a lunch entrée. We can eat in the cafeteria too, for €5 a week (four courses, usually, a starter, main course, cheese and pudding) but the quality is variable, depending on which class has been cooking which course; if we get the youngsters who are just starting out, it tends to be simple fare prepared…well, prepared below the standard you might like to find even for €5; if it’s our class, you’d be happy paying up to €6. In fact, as I discovered recently, those of us doing the ‘continuing education’ course one day per week spend as much time in the kitchen in our one year as those doing the same course over two years (normally the 15-17-year-olds). They get one ‘TP’ – ‘Travail Pratique’ or ‘Practical work session’ per week, which lasts for the equivalent of one service or half a day – four hours. They’re also limited by law to working a 35-hour week – Restaurant Chef tells me that, when he did his training, they worked a 53 hour week (and, probably, also lived in a cardboard box in middle of t’ road) and did four or five TPs in their school’s restaurants and loved it, too. This story was easily topped earlier this summer (we heard it more than once from Chef over staff meals when he was telling the latest crop of stagiaires just how lucky they are) by our Second de Cuisine, Christian – he’s in his mid-50s, and when he started out on his apprenticeship at the age of 14 his first duty every morning was to fill the stoves with coal – yes, coal-fired stoves as used by Carème and Escoffier! So, obviously: Young people today, blah blah blah… Then it’s our ‘Droit’ class, Business Administration (Droit strictly translated means ‘Law’, but since French has the smallest vocabulary of any European language some words have to double up on meanings). As usual, we get 10 minutes worth of information spread out over an hour – teacher is more used to teaching recalcitrant 16-year-olds than attentive adults, and it shows. The hardest part of this class is staying awake – that and working out its relevance to cookery half the time: yes, it’s useful to know about the different types of limited companies one can form, but as I say, it’s 10 minutes worth of information. Then we discuss ‘Partenaires de l’Entreprise’ – clients, suppliers, banks, the State, accountants…There is, I’m almost sure, a reason why we are being told this stuff and each week I keep waiting for the penny to drop as its relevance to cookery becomes apparent - only to realise, after an hour, that the penny has rolled away under a table in the corner, never to be found again. Still. We learn how to make fumet de poisson this afternoon – how to make fish stock, which we do with the remnants of the rougets, the red mullets we trimmed, scaled, gutted and filleted this morning. Again, this is something I’ve done at work – dégorger the bits (leave them in a bowl under running water to remove the blood), sweat the GA (Garniture Aromatique of onions, shallots, leeks, carrots and mushroom peelings), raidir the fish bones – sweat them a bit over a hot flame – moisten with just enough white wine and water to cover the whole lot and simmer for just 20 minutes. I thought stocks took longer, but this is where we learn that yes, veal and beef stock take hours, days even. Fumets take tens of minutes. We filter, re-boil and then put the fumet into the rapid chiller to bring its temperature down to under 10 degrees centigrade within two hours as required under the health and safety HACCP (Hazard Analysis and Control of Critical Point) regulations. This fumet is the basis of the court mouillement we’re going to use to cook our filets of rouget; it turns out that the English for ‘court mouillement’ is ‘court bouillon’, which seems strange – replacing one French word with another. Court bouillons, according to both Chefs, are spicier than court mouillements, and mouillements may also contain poshly-cut GA since it may be eventually served to clients. We also turn more carrots and turnips and cook them slowly in a little water, butter, salt and pepper – ‘Glacé à blanc’, unlike last week when they were cooked à l’anglais - boiled in salted water, in other words. Every French person thinks that everything is just boiled in England. The idea of glacé à blanc is not to colour the vegetables at all but to leave them with a nice, glossy finish. We achieve the same effect in the restaurant by blanching them as normal, then reheating and finishing them in hot water laced with a little olive oil, a process that is much easier as far as I’m concerned. Still, the text book says… We’re also supposed to tourner, decoratively cut, our mushroom caps, giving them a sort of spiral finish. Hmm, is the conclusion here: no one, not even Chef, manages to do this one convincingly. Another one to practise at home. The rougets are decorated (one in two filets anyway) with courgette ‘scales’, courgettes sliced and placed on the fish to resemble giant, green fish scales. Not only do the scales have to stay in place while cooking on top of the filets of rougets swimming in the fumet but they also have to be cut just thick enough to be cooked in the seven minutes it takes to cook the filets - but not be so thick that they’re not slightly translucent, allowing you to see through them to the red of the fish skin. And you have to keep the filets warm while reducing the sauce, but only warm - put them somewhere too hot and they continue cooking and dry out. We cook the rouget filets and reserve them - keep them warm enough to serve but not so warm that they continue cooking - then reduce down the cooking juices to make a very nice sauce; the whole lot gets wrapped and chilled for lunch for tomorrow’s students, lucky devils, as Filets de Rouget Sauce Bonne Femme. And even though we seem to have done lots today we have half an hour left to discuss ‘progressions’, those sheets we need to fill out at the start of our exams showing what we plan on doing for the four and a half hours of the event in 15 minute sections. It’s quite hard to get your head around this idea to start with, but it is blindingly, obviously important – you need to have worked out at the start if something is going to take three hours to cook, rather than realising this 15 minutes before you’re due to serve it. Chef gives us some blank forms and tells us to pick a few recipes out of our text books to practise on for homework.

-

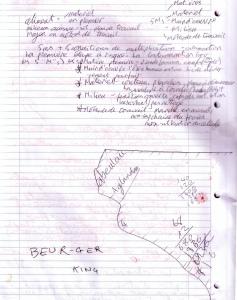

18: 'Murican style Delphine drives me to school this morning. I’m still not up to cycling, so she drops me off on her way to work and I’ll get the bus home this evening. I apologise to Chef for missing last week and he checks to make sure I’ve been given the recipes they worked on while I was away. I’ve already copied them from Mr Whippy – Pascal, the guy who shares my workstation and who can whip anything into a better froth than I can. Including, obviously, the genoise they made last week. Chef moves on. I can’t tell if he’s mad at me for not coming last week or disinterested – he doesn’t seem impressed at my tales of the doctor wanting to cart me off to hospital. Clearly, unless you’ve lost entire limbs, preferably more than one at once, you should come to work. Not being able to work out which way is ‘up’ is no excuse at all. So today we’re doing ‘Poulet à l’americaine’ and, like so many things given foreign names by the French, it bears little resemblance to anything Americans might do to a chicken. Well, that’s not true – essentially American-style chicken in this case means quartered and grilled with a tomato sauce, but Americans aren’t the only ones to treat poultry thusly. Mind you, Americans get away lightly – just about the only foods the French have named after the English are ‘légumes a l’anglais’, vegetables boiled in salted water, and crème anglaise which is really nothing like custard at all (no powdered eggs, for example). Everything else à l’anglaise is really quite rude – try checking out ‘J’ai les anglais qui arrivent’ or ‘Filer à l’anglais’ if you have a strong stomach. NSFW. American chicken starts, as do all good French recipes, with some good stock; chicken, in this case, or ‘fond brun de poulet’, chicken stock made with roasted bones. At the restaurant we make our own but, since we don’t have enough time at school today, we use the powdered stuff. Add in a little tomato concentrate, carrots and onion and we’re good to go. Well, good to start going. You take this sauce, reduce it down and then ‘diablé’ it, devil it by adding chopped shallots, white wine, white wine vinegar and ‘poivre mignonette’ which, literally translated, means ‘cute little pepper’ but in practise means cracked black pepper. ‘Diablé’ because anything vaguely hot in French gets a wicked name – the French simply cannot cope with hot, spicy food and need to give it a name that says ‘Warning! Warning! Danger of Death!’ Wimps. So then we actually get down to grilling the chicken, first scrubbing the hot grills (cast iron plates that sit over a couple of gas burners) and then, well, grilling the chicken on them after seasoning and oiling the meat. This makes pleasingly large flames to frighten the girls, which is always fun. We grill a few tomatoes and mushrooms too, and finish the whole lot off in the oven. Which sounds like a simple idea but is something that had simply never occurred to me to do before I started cooking professionally. Grilling things on hot pans gives them a nicely coloured exterior (Maillard reactions! Look it up!) but then goes on to burn the meat if you leave them on the hot gas. You can turn down the gas and keep turning the meat repeatedly, but it’s simpler to whack the whole thing into the oven and let it finish off there at a lower temperature, cooking the inside through without burning the outside. Good tip there, food lovers, which only seems obvious once you know about it. Midday today and I eat a quick lunch to give me time to copy up notes from last week’s classes – the people involved in the justice system (judges, lawyers, bailiffs and so on), plus ‘La fiche de stock’, stock sheets which is how you’re supposed to keep track of what’s in the pantry by checking stuff in and out. I’ve never worked in a big enough kitchen to warrant using such a thing – they’re all small enough to stand in the pantry or cold room and say, ‘Hmm, I see that we need more flour and aubergines.’ Much less complicated than the enormous sheets Chef has handed out where you need a minor degree in accounting just to work out how much olive oil you have and whether you should order some more. Yet another thing that, if you need to have it, would be easier to do on a computer but all the French restaurants I’ve seen bar one have used exactly no computers at all. And that one used wireless handsets to take orders which were then printed out and passed around the kitchen. Then on into a Hygiene class where we learn more about bacteria, including the fact that it takes just two hours for them to multiply in whatever food you leave lying around to reach critical mass, the point where they gain sentience, rise up from your work surface and suffocate you in a glooping mass of grey goo. Well, I exaggerate slightly for effect but that’s the general idea. It seems obvious to me that some things will go off more quickly than that, while other things can be left out for a lot longer than two hours, but again for the purposes of passing this exam the limit is two hours. We also learn about ‘sporification’, whereby the spores of bacteria can survive even boiling and that the only way to kill them so they can’t hatch into new, killer baby bacteria and fill your life with grey goo is to sterilise them at temperatures over 140 degrees Centigrade. And then you can re-contaminate stuff by, say, letting beetles crawl over it when you leave it uncovered sitting on a windowsill. Good grief. All fine stuff but it doesn’t take an hour for a grown adult to understand it. 2818566224_3c58e2625f_bThis picture shows what I do for the next 50 minutes after I’ve grasped the meaning of this week’s lesson (which, don’t forget, is being given in French so I have to translate it first before I can understand it. The text at the top is my notes on bacteria. ‘Aglandau’ and ‘abeulau’ refer to two different types of olives from which olive oil is made – David and I were having a discussion about the merits of each instead of paying attention to teacher. ‘Beur-ger King’ is the name of a new, Arabic chain of burger bars recently launched in Paris, ‘Beur’ being an Arab word. The sums are me working out my wages and tax owed thereupon. The drawing bit is me doodling.). I love the practical cooking parts of this course, and the classes on cooking techniques. And while I understand the necessity of teaching hygiene, nutrition and legal stuff to future restaurant chefs I do think it could be done more by way of handing out a small pamphlet at the end of the year, rather than making a group of grown-ups with better things to do than sit in a hot room and have a nap. We do Quiche Lorraine this afternoon. The quiche is fine, any fule can fill a pastry case with flan, vegetables and bits of bacon. Bacon, of course, is counted as a vegetable in France so Quiche Lorraine is a vegetarian dish over here. I jest not; I’ve since worked for a couple of weeks in a restaurant where the ‘vegetable of the day’ was regularly ‘flan aux lardons’, flan with bacon bits in it. When I explain that, of all the ingredients – milk, eggs, bacon – none come from the food group known to the rest of the world as ‘vegetables’, I’m told ‘There’s salt in it!’. Well, salt isn’t a vegetable either. But flans are, apparently, so Shut Up. Back home on the bus. Bus routes are the same all over the world – this is my first trip on a bus in Avignon and its route planners have followed the rules used by bus route planners everywhere: check departure point, check arrival point, draw straight line between two, then visit every other place you can think of within three kilometres of that line so the journey takes an hour instead of 10 minutes. And above all when you’re within 500 metres of the arrival point make sure you take an extra detour so as to frustrate passengers to the maximum. And then back to bed. Standing up all day from 8 am to 6 pm has done me in.

-

17: Result: I'm officially ill 14.5 out of 20 for my exam at the end of last term, which I was very pleased with indeed, third in the class behind David, who’s a waiter-turned-cook working in a posh restaurant north-east of Avignon, and Beatrice, the Belgian owner of a very smart local chambre d’hôte bed-and-breakfast. And then Philippe our teacher let slip that he’s marked us down ‘very severely’ and that for our proper CAP exam we could expect to do a few marks better than the scores he’d given us. Result indeed, that’s gotta be a good 18 or 19 out of 20 for the real thing. I was let down by my ‘commercial presentation’ – talking about the dish I’d prepared. I misunderstood the question asked, and chatted about the ingredients and techniques I’d used as if I were talking about it to my chef de cuisine. In fact, I’d been asked to present it to a customer who would want only general details and to be told how delicious the dish is. Lesson learned. But that’s the only good news today because I’m feeling very, very poorly indeed and got Delphine to drive me to school this morning because I was feeling so bad. It’s a flare-up of a condition I’ve been suffering from on and off since 1997, when we first started looking for a house in France. Then, we were staying in a B&B just west of Nimes and I was feeling fluey, which I put down to a long drive from London and just general tiredness. I woke up at about three in the morning dying of thirst and completely disorientated, and fell out of bed. I was trying to get up and go to the bathroom but was so badly disoriented and confused that I actually couldn’t work out which way was ‘down’ in order to push myself upright, and had to be physically dragged back into bed. By the time the doctor came in the morning I wasn’t feeling too bad, and he took blood samples and sent them off for tests but couldn’t find anything. I was worried I’d been bitten by something – the day before we’d been to the Camargue and I was worried that a malaria-laden mosquito had bitten and infected me. Which is rubbish, of course, the Camarguais mosquitos live a few thousand kilometres north of their malarial cousins in Africa. Still. There are poisonous spiders in the vines, everyone said. And scorpions. And I was definitely suffering a bite, my leg had swollen up to three times its normal size and hurt like mad. So this morning at school I can feel the symptoms recurring, as they have done just about every year since 1997: flu-like feelings, leg swelling and soon I’ll get the shivers and shakes so violent that I can’t stand up, so I excuse myself at 10 am and go home for a lie down. Before I leave Chef gives me the recipes for today, black forest gateau and paupiettes of merlan (whiting) which I promise to do later this week. And then I go home and spend 24 hours in bed, shivering and shaking, before the doctor comes to see me. She does lots of tests which, I tell her, will be useless; I’ve seen lots of doctors and specialists over the past nine years and none has ever found a solution. But French medicine, supporting as it does the Best Health Service in the World, diagnoses my problem. I have, it turns out, an ‘erisipel’, a blood infection. I have – have always had, since my early childhood – athlete’s foot which comes and goes and I control with topical creams to kill the ‘champignons’, the ‘mushrooms’ as the French so delightfully call the fungi. Every now and then they get into my bloodstream via a cut or break in the skin on my foot and infect my whole body – my leg swells up as it’s nearest the site of infection. My doctor says I need to go to hospital immediately since this is a very serious problem and I could die if I don’t get it sorted out. Ha! Has she never heard of the Cook’s Code of Conduct? Rule 1: Always Go To Work, No Matter What. Rule 2: See rule 1. My restaurant is officially closed at the moment, but I’m working with the Chef on a few passing groups and our resident group of Gendarmes (groups of CRS Gendarmes, the French riot police, are regularly stationed away from home all over the country and we have a permanent group staying in the hotel). So as it’s just me and him there’s no question of me leaving him to work alone so I tell her to find another solution. Hmm. Well, says the doctor, you could take this, and this, and this and use this cream and this special soap and lie in bed at home and a nurse will come round and give you twice-daily injections in the stomach to try to stem the infection. Eight prescriptions? I must be poorly. In France, others judge your real level of illness by how many items you’re prescribed – one or two and you’re clearly faking it. Three or four and yes, well, OK, you might be a bit sick but it’s not serious. Five or six items and you’re definitely poorly, take the day off. Eight items, plus a nurse coming round morning and evening to give you an injection? Now you’re definitely sick, lie down straight away. So I go with this option, except the only nurse I can find in the yellow pages who will take me on doesn’t do home visits so far away from home (she’s a five minute walk from my flat) so I have to schlepp round there twice a day. Me, who’s supposedly so ill I should be on a drip in hospital. Anyway. So I do that and continue going in to work too, collapsing in bed as soon as I get home. Delphine is working at the moment but, sterling trooper that she is, manages to drive me to and from work most days and I get the bus the rest of the time rather than taking my bike – I’m really not up to cycling the five kilometres to the restaurant.

-

Me too, dating to 1987 I reckon.

-

16: Self-examination We have our first all-day test exam today, with written papers in the morning and practical this afternoon. It’s the first time I’ve done any exam papers at all for 20 years – and back then, at the age of 25, I sat in my final exam and calculated that it was exactly my 50th public exam (not counting the probably hundreds of test exams I’d sat at school and university). I promised myself on that day that I would never, ever sit another exam paper for the rest of my life. So here I am taking my 51st exam. All in French. The written parts are all based on previous CAP (Certificat d’Aptitude Professionel) exam papers but only covering what we’ve studied in the past three and a half months (three and a half months already?). So there’s a hygiene paper where we get asked about the five conditions necessary for the development of bacteria (37 degree heat, water, protein and the presence or not of oxygen), a business practices paper (calculate how much money Monsieur Marsaud has left to spend after he’s paid his rent and mobile phone bill every month) and a kitchen technology paper. The latter is the hardest for me, partly because all the vocabulary on this has been new to me this year, and partly because the photocopied photograph of a kitchen range on which we’re supposed to label everything is smudged into an indistinguishable grey mush. So that thing down the end is either a deep-fat fryer or a bain marie. I plump for the latter, and it turns out to be a sauteuse. There you go. The practical this afternoon is what we all see as more important. It’s the only ‘failing’ section of the exam – fail any other part and you can still make up the marks you need elsewhere; fail the practical and you fail the exam completely. Which is as it should be. Read more... We have to produce two dishes in four hours, a chicken curry and an apple tart. We do get given the 'approved' recipes but have to check them carefully - exam setters are known for slipping in deliberate errors to try to trip you up. Tablespoons instead of teaspoons of salt, for example, or setting the oven to 300 degrees C. As we’ve been taught, I set to writing down on the back of my exam paper which order I should be doing things in, and conclude that I should butcher the chicken, put the bones to roast and then make a stock while doing my veg, prep my pastry and then put stuff on to cook while that’s resting, then finish the apple tart. That way, all the ‘dirty’ stuff – meat, veg prep – is out of the way before I use my work area for making pastry. Then I look up and see that at least half the class has started out by making pastry. Hmm. The temptation here is to join them just because it’s what everyone appears to be doing, but I have confidence in my calculations and it works out fine. We all finish at about the same time, but I’ve spent less time cleaning my workstation and more time cooking. In France, ‘Chicken curry’ is essentially a fricassée of chicken with some curry powder stirred in; they’re not big on authentic, Indian sub-continent cookery here and definitely not into hot-tasting foods so I moderate the amount of curry powder I put in. The apple tart is a ‘tarte fine’, pronounced feene, which is a circle of blind-baked pastry, crème patissière and then the apples sliced thinly and arranged attractively on top. Everyone knows what these things look like because they see them every day in the patisseries in town. We also have to do a Pilaf rice to go with the curry, and not everyone succeeds with this; several rices get burned when they forget the 17-minute cooking time, others go soggy when they get stirred immediately after being removed from the oven by those curious to see how they’ve turned out. I remember the 17 minute rule, the no-stir rule and it works out fine. The curry’s good too, and I serve my plated meal and my two side dishes with the remainders in good time. Just as I’m returning to my workstation I notice my neighbour about to set off with his plates; “Julian, you’ve forgotten the diced-tomato garnish!” I warn him. Stoner Julian, ever laid-back, replies simply, “Yeah, I was hungry, I ate the tomato.” I lend him some of mine, generous person that I am, but see him picking at it on his way to the examiner. So check any curries you eat in France carefully – if the diced tomato garnish is missing, your meal may well have been prepared by a hungry stoner. When we’ve all finished we clean and scrub the kitchen – there’s a collective mark for the condition of the place at the end of the exam so it’s worth doing it properly. And then we’re free for the next two weeks of school holidays, two weeks during which we can remember every mistake and error and fault in the dishes we prepared…. And, obviously, during which I will NOT be on holiday but working like a dog in the restaurant.

-

15: A side of English The French people with whom I work are always smugly pleased when one of the two English-named (or so they think) dessert dishes they know of comes up. The first is crème Anglaise which they translate as English Cream and English people translate as Custard. The French make this by beating together 8 – 10 egg yolks with a little sugar, stirring in a litre of almost-boiled milk then returning the whole lot back to a gentle heat until it reaches the thick coating stage. If they’re trained professional patissiers like me (OK, five minutes’ coaching by my Chef but it amounts to the same thing) they only add half the boiled milk to the yolks and sugar, whisk well and then return it to the pan – this avoids the mixture getting too cold. The English make Custard completely differently, I explain. They open a packet of Custard Powder – Birds in the yellow and blue and red packet is the traditional one – and add a couple of tablespoonfuls of milk from a pint to the powder along with a random amount of sugar, stirring it into a sticky goo. When the milk boils, they mix it into the goo with a spoon and then re-boil the whole lot. Birds’ custard powder contains, as far as I can tell, powdered eggs and cornflower and nothing of any nutritive or flavour value whatsoever. But it is yellow and sweet. The other English dessert French people go on and on and on about is Pudding, pronounced ‘poodeeng’. This, they fondly imagine, is called ‘pudding’ because it’s what English people always eat for dessert after a large dish of over-roasted beef and too-boiled potatoes, in much the same way that the French live exclusively on garlic-laced snails, frogs and baguettes. Well, if you’re English or have ever eaten in that country, see if you recognise this: Take all your leftover bits of ‘biscuit’ (this means sponge cake, not real biscuits); soak them in milk; add a few beaten eggs; pour in a little rum; pour the whole lot into a terrine mold and bake in a bain marie for an hour until it’s perfect, with ‘Perfect’ in this instance meaning ‘gooey mess’. Might be nice with some custard, I suppose, but the French will insist on serving it cold. So we do crème anglaise at school today, to go with the Genoise sponge we also make. I have problems with this once again, mostly because of my old journalistic injury – messed-up carpal tunnels. I had the left one operated on at the start of last year and it only hurts occasionally, but the one in my right wrist needs doing to return my whisking hand back to decent, frothing form. This means I find it hard to whisk stuff like egg whites and genoise sponge mixtures long and hard as one needs to do, so my sponge failed to lift as much as it should have done. This is one area where Pascal, the chap with whom I share a workstation at school, excels over me – his right hand is a blur of motion as he beats away…And again, this is one area where we do things differently at work – at school we beat the genoise over a bain marie; at work it’s directly on the hotplate. But my crème anglaise is fine and I manage to slice my genoise into three layers despite it being Not Very Thick (thank you, Chef, I had noticed that in fact) and fill it with apricot jam (the French love apricot jam and treat it as if it were edible). While all this is going on, our stock pots are bubbling away in the background. Stock is something I’ve sort of always known to be important, and indeed we made a pot of it during our first week at school. Now we make it every chance we get, and today we’re practicing making a fond brun lié with the carcasses of our Poulet Sauté Chasseur. Which is, in the end, a lesson in why Stuff Tastes Nicer in restaurants than it does when you try to make it at home: it starts off by being made with decent stock and finishes off by being, er, finished off with real butter. The chickens – two of them – we learn to cut up raw, removing the suprèmes – the breasts with a wing attached to each – and the legs, complete with the ‘sots y laissent’, the ‘idiots leave behinds’s, what in the UK we call the Oysters, the small round oyster-shaped bits where the legs attach to the body. The idea is to take all the skin and flesh and leave the bones – for a fond brun. Brun – brown – because we roast the bones in the oven first until they’re brown with a garniture aromatique of carrots, onions, garlic, tomato paste and a bouquet garni. The ‘lié’ – liaison – part comes when we add some powdered stock powder which contains cornflower. Quite why we need to do this both I and David, the only other chap in my class who’s working in a posh restaurant, agree is impossible to know so we both leave it out and get the thickness required by reduction and, if necessary, a little Maizena, regular cornflour, at the end. No no, says school chef, we need to know how to use PAI, Produits d’Alimentation Intermediare or mid-way food products (mid-way between raw ingredients and finished items, i.e. something which has already had something done to it and which needs something else doing to it to make it edible – like frozen peas). These are becoming Very Big in the French catering industry, he tells us. Indeed as I’ve said before, there’s a huge discussion going on about how the entire qualification I’m doing, the CAP, should concentrate on using PAIs instead of how to make stock. This is because the big chains like Accor who have a lot of money to lobby the government like using PAIs because they get cheap consistency of product ('product' is what chains call food) on their dining tables. It may go that way, but it won’t be me opening the packets for them. So while my chicken portions are roasting in the oven (12 minutes for the suprèmes, 15 for the thighs) after being browned on the stove top, I make my Sauce Chasseur from the Fond Brun lié with some chopped tomatoes, finely chopped shallots, mushrooms, fines herbes, white wine and cognac. Reduced down to a decent napping consistency I then monter it au beurre to give it a really delicious taste. A handy tip this for working on sauces at home – never be afraid to whisk in a little (or even a lot) of unsalted butter to many sauces. You reduce down the liquid part of your sauce and then whisk in cubes of cold butter one or two at a time until your arteries clog up and your doctor has a heart attack.

-

Exactly. Raw radishes do nothing for me, cooking transforms them.

-

14: In the soups There are, it turns out, rather a lot of soups. Going back to the days of Escoffier and earlier, rather than calling soup with carrots in it, ‘Carrot Soup’, the French call it ‘Potage Crècy’, named after either Crècy-la-Chapelle in Seine-et-Marne, or after Crècy-en-Ponthieu in the Somme. Both claim they grow the best carrots and the best soups, both claim Potage Crècy (and anything else containing carrots) as their own whilst declaiming the others as lesser, impostering, worthless, tasteless, rank rubbish-vendors. The French are never prouder than when boasting about the superiority of their local produce. I mean, just look at the table we got given today; there are potages where you start with carefully sized vegetables, puréed vegetables, puréed dried vegetables, with creams and cream-liasions, consommés (aka clear potages), bisques, cold potages, regional specialities…”You need to know all the families plus one or two examples of specific soups within them,” says school Chef. So yes, we have to know that split-pea soup is really Potage Saint Germain and not just split-pea soup, that a Consommé Madrilène (served with straw-diced red peppers) is chicken consommé with chopped fresh tomato pulp in it, and that if you really want to start an argument in a room full of Provençal cooks you start telling them what to put into a Soupe au Pistou – man, the guys and gals in class went over that one for a good quarter of an hour. It’s a good job our knives were across the other side of the building in the kitchen, otherwise blood would have flowed. Not least mine for suggesting that, like bouillabaisse (fish stew), it’s really made up of whatever vegetables and herbs you have lying around. Blimey, you’d have thought I’d asked for a well-done steak. So, over in the atelier we do a Potage St Germain aux Croutons – split-pea soup with croutons, as I think you say in English (I’m remembering fewer and fewer words of your language with each day that goes by. Désolé.) It has the washed and blanched split peas, blanched and fried lardons of bacon, leeks and white veal stock. Then we do a Velouté Dubarry, which is ‘velvety’ veal stock with cauliflower, cream and egg yolks. With both I learned something I’d never thought of before – after mixing them with the giraffe (the large, hand-held mixer you plunge into the saucepan and which, in our industrial-sized case, is about the size of a decent pneumatic drill) and then passing the mix through a chinois, you should re-boil it again since you can’t guarantee the cleanliness of the giraffe and chinois. This afternoon – after a singularly unappetising lunch in the school canteen of very wishy-washy cod mornay (we’ve discovered that the stuff we cook on Mondays is usually served on Tuesdays when the school director makes a big deal of eating in the canteen with the plebs instead of in the private staff dining room or the gastronomic restaurant next door where the final-year kids get to cook) – it’s Entremets Singapour. What’s an entremet? Well, the fact that the Larousse Gastronomique feels it necessary to devote nearly half a page to the subject should clue you in to the potential problem here. The word means ‘put between’ and basically, it’s anything served after the meat course. Generally it means puddings, but in big restaurants the entremettier will do savoury soufflés, pancakes and pastries plus sweet entrements like sweet omelettes, rice puddings and ice creams. But then Taillevent reckoned to also include things like oyster stew and almond milk with figs and “swan with all its feathers” in the list of possibilities, although this latter item is apparently not something we’d be expected to produce for our final exam. Instead, Singaporean Entremets are a Genoise sponge (this is a very international dish) cut into three horizontal layers with crème patisserie between the layers. Again, I have trouble getting my Genoise frothy enough because of my RSI-ed wrists. I must think about having an operation again when the restaurant is closed in January. Talking of the importance of regional produce, back in the restaurant we had the Frodd Squodd (Frodd is how the French mis-pronounce Fraud) from the Service Veterinaire (which is what the French call the Health Inspectors – no, I don’t know why) the other day. They were checking that our Poulets de Bresse really are from Bresse and not some hut up the road. This is very important in a country where, if your lentils aren’t from Puy, they’re inedible. Well, that’s what French people think, anyway. Same with most things – cherries, almonds, ducks, lamb, salmon (must be from Scotland – you know, that place to the North of England from which no English person would buy salmon any more as it’s all poisoned, apparently), everything has its origin. There’s even the AOC (now IGP) system to regulate this sort of thing – AOC applies not just to wine but butter, milk, olive oil, you name it. So the Frodd Squodd spent half an hour reading our menus and checking our bills and labels and the contents of fridges and cold rooms, and pronounced us nearly clean. We need, they said, some way of indicating the origin of each mouthful of beef rather than just having a line on the menu saying it could be from France, Holland, Belgium or Germany. A blackboard at the entrance, perhaps, they suggested. Can’t see it happening, somehow. In the same way that Chef refuses to acknowledge their advice on keeping eggs (he keeps them in a kitchen annexe rather than the fridge), I can’t see us erecting a ‘Today’s Specials’!’ blackboard in the dining room.

-

13: Vacuum-packing Pancakes up first today. Well, crêpes really; French people generally disdain ‘pancakes’ as overly-thick American creations (as in MacDo breakfasts) suitable only for use as fire blankets and airplane wheel chocks. So, crêpes are lace-thin pancakes, as you probably already know. And, as most of us in class are either French or cooks or both, most of us have already made the odd one or two in our lives. So today’s competition is to see who can make the most crêpes with the half-litre of mixture we make up. I get 24, Eric – who makes these damned things every day (note I’m getting my defence in early) – managed 30. but they weren’t all complete, and didn’t taste as nice as mine anyway. So there. We use them to make ‘Aumonières Normandes’, small parcels with butter-fried diced apples inside. Very yummy and, for once, we get to eat them as we take them over to the self-service cafeteria where some of us eat every week. The quality of food in the cafeteria is, as I may have mentioned before, variable. This week’s it’s edible, though, veal chops with mixed vegetables. The veg look very regularly diced into a lovely brunoise from a distance, and tasting confirms that they’ve come out of a tin. Our class doesn’t get to do TPs (Travails Pratiques, practical work sessions) in the caféteria kitchen, but the youngsters doing the same course as us but full-time over two years get regular sessions there. Some, it’s obvious, like it more than others. There’s a big debate going on in the French catering industry that this qualification, the CAP (Certificat d’Aptitude Professionnel) should be more oriented towards opening cans and microwaving vacuum-packed mush. A debate led, of course, by Big Business, the sort that have large chains of restaurants where economies of scale (the scale economy of employing low-talent droids to push microwave buttons instead of people who know how to prepare fresh veg) are important. The small businesses want cooks who can cook, of course, but lots of little voices are drowned out by the few big, loud ones. Me, I’m happy to be getting a classical French cooking training in the heart of Provence from a great school chef and an excellent restaurant chef. I count my blessings daily, knowing that French cuisine is slowly changing and not for the better. Or at least my weekly blessings. Not during, for example, our ‘Droit’ class, which we have this afternoon. Today we learn about “business partners” – clients, suppliers, “l’état et les organimsmes sociaux” financial partners, banks, investors, you name it. And then, just for fun, we do a household budget – work out that, if Monsieur Marsaud spends X on electricity, Y on food and Z on his mobile phone bill then he has only 38 cents a month left to live on. Or something like that. Perhaps he can eat microwaved meals in a local chain restaurant. This afternoon we do Carré de porc poélé ‘Choisy’ – Choisy in this case meaning ‘containing lettuce’. Our lettuce is first poached in hot water (départ à chaud) – I’m learning about what vegetables to cook in hot water or cold water, and how important it is to refresh in iced water immediately after cooking to preserve the vitamin and mineral content, enhance the colour and halt the cooking process before it turns to the sort of mush you get from microwaving vacuum-packed rubbish…(OK, I promise to stop going on about this. Can you tell my Chef has been indoctrinating me? Although we use sous-vide – vacuum-packing – a lot in the restaurant, he hates the microwave and doesn’t actually have one in his home kitchen. The one at work is used for defrosting breadcrumbs. Then we have to form the lettuces into a ‘fuseau’ which is either a spindle, or one leg of a pair of ski pants, so I’m going for ski pants and achieve the required effect (if you wear huge, baggy ski pants like I do). This is then cut in two lengthways and braised in the oven at the same time as the Carré de porc, the section of pork ribs we each have to de-bone and cook. We were going to have a run of four ribs to de-bone and cook whole and my restaurant chef has been ordering them in all week for me to practise on. Which, as it turns out, means I’ll be the only person doing such a thing this week since our school ones arrive frozen and already sliced into individual chops. We do get to cut one of the bones off each chop, but it’s no real challenge. We do try following the rest of the recipe (cooking the pork in the oven with a regular GA, garniture aromatique of onions, carrots and a bouquet garni) but it seems slightly futile to try and re-assemble the chops into a joint at the end. So we don’t do that. The lettuce is very good, though, I’d never really thought of using them as a cooked vegetable. Like radishes, which we also cook at the restaurant.

-

I took almost no photos at the time I'm afraid, this was before the days of universal smartphones. I'll try to turn some vegetables and post pix for you though!

-

Thanks. I've already written somewhere that Ruhlman's first day at cooking school was the same as mine - making veal stock.

-

12: English cooking The French are initially surprised to find an English person cooking at all. There’s a famous TV advert here for After Eight chocolate mints which shows a group of BCBGs (French for ‘yuppies’) eating After Eights with their post-dinner coffee and finding them distinctly edible, if not positively quite nice. “After Eights,” the tagline runs, “they’re English – but they’re good!” Then they start asking about ‘La Cuisine Anglaise’ – English cooking – and what sort of stuff English people cook at home. Well, here we’re leading the French, I tell them – we’ve been buying cooked/chilled ready meals by the tonne and nuking them in the microwave for more than a couple of decades. French people are doing their best to catch up now, I tell them, and then they start talking about the Traiteurs they have – shops where you buy freshly-made (well, normally freshly-made) portions of restaurant classics and, er, zap them in the microwave. And anyway, traiteurs are closing down all over the place because they can’t get the staff and they’re too expensive to run and the supermarkets are filling up with cook/chill dishes… And then, after a quick detour to laugh at ‘Lamb with mint sauce! Ha ha ha!’ they say Ah! Oui! Légumes à l’anglaise! Vegetables cooked in the English style means boiling them in salted water. So now they remember that English people boil the crap out of just about everything, usually all in one giant vat-like pan for three or four hours. Which isn’t that far from the truth in some cases – one of the few stories I know about my great-grandmother Loseby was that she used to boil tripe and potatoes in the same pan. For three to four hours. So today at school we’re cooking Merlan à l’anglaise, which turns out not to be boiled but to use that other great traditional English cooking method, frying in a pan of oil. Merlan is similar to the English Whiting and American Silver Hake and is a member of the cod family. We use it often at school because it’s cheap – we don’t serve it to customers at the restaurant, although it does feature sometimes in staff meals. To prepare it à l’anglaise you have to remove the gills first and drag the entrails out with them through the gill slits, without cutting open the belly. This is easier to do than it sounds, fish turn out not to be very attached to their insides. Then you open it along the spine, rather than along the belly as is more normally done, removing the bones as you do so. Then you fan it out but leave the head in place. The body is coated in flour, egg and breadcrumbs and pan-fried, leaving the head in place to stare up accusingly at those about to eat it. I can’t see English people ever eating fish like that these days – most think that fish swim around shrink-wrapped in polystyrene trays if they think of fish swimming at all. And normally, I tell my French friends, they eat only the fingers of the fish these days, an idea that amuses French people no end since they, like Americans, eat fish sticks not fish fingers. By now I’ve done lots of fish at work so I don’t find the whole procedure too difficult; it’s really a way of practising various knife skills, I realise, since this is now a very old-fashioned dish which you wouldn’t see in any restaurant even over here – too much effort to start with and the French, especially younger ones, are starting to not like things that stare back at them from their plates. Many people have real difficulties cutting out the spine and then de-boning the still-joined filets, and end up with something that looks like it’s been given a good kicking by Manchester United fans. Still, that’s why we have breadcrumbs, “Pour cacher la misère” – to hide the misery, as my restaurant chef puts it, normally when he’s surveying something I’ve messed up in the patisserie. Be very suspicious if you buy a pudding in a French restaurant and the sauce/custard is poured over the tart/pie/whatever instead of in an attractive pattern onto the plate around it – it means the patissier has really messed it up and is hiding his errors from you or, more likely, his Chef de Cuisine. Two nice thick coats of breadcrumbs and we’re ready to go. We also do Petits Pois Paysanne, little peas peasant-style, in which peas are the least of the ingredients – there’s carrots, turnips, baby onions, lettuce and bacon bits in there outweighing the peas two-to-one. Which is fine if you don’t particularly like peas and want to hide them – but then you’d probably be better off cooking the whole recipe and just leaving out the peas. After lunch we have our regular fortnightly Hygiène class, this week talking about Glucides – sugars. Which apparently should represent 55% of our diet, particularly from ‘glucides lentes’ – slow sugars – such as those found in pasta and, apparently, bread. As little as possible should come from pure, refined sugar. Glucides, we learn, are where we get our energy from for our muscles and nerves, and we need 100 grammes per day. We also need 15% of our diet to be protein and 30% lipides – fats. Right. So I’d better put that pain au chocolat away, then? We do légumes à la Grècque this afternoon, vegetables cooked the Greek way, which means slowly in a little water and olive oil after cutting them up into attractive shapes. Artichauts, artichokes first – these confuse many of my culinary student colleagues who end up with something the size of half a ping-pong ball full of fluff. But, again luckily, I’ve done these at work so understand that the idea is to remove the leaves on the outside and the fluff on the inside and put the rest into acidulated water (i.e. with half a lemon squeezed into it and then the lemon chucked in for good measure). Then there’s cauliflowers cut into ‘bouquets’ which just means bite-sized pieces, escaloped mushrooms (cut into quarters on a slant, although even our school chef says he finds this idea impossible to accomplish), diced onions, chopped garlic, a bouquet garni and a ‘sac aromatique’ to prepare. The ‘aromatic bag’ is a bit of cloth with any interesting-looking spices you can find bunged in, which turns out to be a bit of old nutmeg and some peppercorns, being the only things left lying around the school kitchen. And since each vegetable needs to be cooked on its own it means a bouquet garni and ‘sac aromatique’ for each pan. And as there aren’t that many saucepans in the room we have to group our cooking, which is fine by me unless we then have to present a plate to be marked – not everyone turns their vegetables as well as me and I’ve been marked down before for featuring vegetables from someone else on my demonstration plate - thankyou Rashid. Still. A la Grècque cooking turns out to be very similar to our teacher’s favourite way of cooking most vegetables – à blanc, i.e. in a sautoir with a little sugar, salt, pepper and butter. Remove the sugar and replace butter with olive oil, cover with a circle of silicon paper and you’re good to go. And in the end there’s no need to make up a plate for service, so my superior English turning isn’t seen by anyone.

-

This is a fairly simple version of veal stock which finishes a grey colour, not clear. You can clarify it using an egg-white or egg-white-and-ground-chicken 'raft', which we used to do in the restaurant but which, frankly, is a lot of faff for home use. Veal stock is the reason why soups and sauces and stews taste better in restaurants than at home - it gives a real depth to the flavour of your dish which you won't get with bought-in cubes. You can buy veal stock in concentrated form now, but it seems very expensive to me compared to this version which is, essentially, free. It takes a while to cook but only perhaps 15-30 minutes of your time. Highly recommended. Ingredients 5 kgs veal bones - many butchers give them away. This is easy to say, but the idea of asking for something like this may frighten you. Don't be frightened. Most good butchers - all good butchers - like customers who like interesting bits of dead animal. They literally throw away tens of kilos of bones every day, and they'll be interested that you want to do something interesting with them. So don't be afraid to ask. You want the good, thick, meaty ones from legs, about 5 cms long - do get the butcher to cut them on her bandsaw for you, it's impossible to do this on your own at home and there's no way you'll fit a 70 cm leg bone into the average kitchen's biggest saucepan. 500 grammes carrots, scrubbed or peeled - your choice. Gordon Ramsay and Anthony Bourdain say you're lazy if you don't peel your carrots. Me? Meh. Scrub them clean, which was the original purpose of peeling, and you'll waste less. Tough skins? Nope. And - especially in potatoes - lots of the good stuff is just under the skin. 1 kg onions - Two or three big ones - peeled and quartered 500g of celery - a couple of sticks - roughly chopped Any other bits of root vegetables you have lying around like turnips or parsnips but no potatoes. Potatoes thicken your stock but not in a good way, they'll also make it cloudy. The total should be around a third to half of the weight of the bones. Some herb stalks. When you use parsley or thyme or whatever, use the leaves as normal and then put the stems in a plastic bag in the freezer, pulling them out by the handful when you want to make a stock. Couple of bay leaves A few peppercorns, whole Method Wash the veal bones - some boil them, but this is an exaggeration. You’re going to be boiling them for many hours so a quick rinse to get the worst of the muck and blood off is just fine. If you want brown veal stock, roast them in the oven at 180C for half an hour or so with half the above quantities of vegetables cut into a mirepoix - pieces about the size of the tip of your little finger. If you want white stock, don’t roast them. Bourdain adds tomato paste to his roasting bones, at school we didn’t. It adds a bit of umami (look it up, it's the good stuff). Put the bones in your biggest pan and cover with cold water. Add in the roughly chopped vegetables and herbs. Bring it almost but not quite to the boil and allow it to simmer very gently. By gently I mean, with a half dozen bubbles popping the surface every minute or two. This is a slow cooking process, if you boil your stock it will emulsify the blood and proteins in the water and give you grey goo. Every 30 − 60 minutes skim off the layer of fat and scum floating on the surface. Do this with a BIG spoon or a ladle - press it gently onto the surface of the stock until the lip just goes under the surface, allowing the scum to float into the ladle. Repeat across the surface until it’s clean again. Top up with water as necessary to keep the bones covered. Stir a bit once or twice to change the order the bones are stacked in. Leave it as long as you can - 4 hours is a very strict minimum, 8 is much better, 10 is best. When you can’t stand it any longer, remove the bones and then strain the liquid through a sieve, a colander or, best, a muslin cloth. Do this at least twice, more if you like doing this. 5 times won’t hurt. 10 times if you have a stagiaire in your kitchen. Store it in small batches in the freezer. You may have 3 − 5 litres of liquid. You can also reduce some of it down by half or three quarters and store it in ice cube containers and then plastic bags in the freezer to give an instant lift to your packet soups (only joking, if you’re caught eating packet soups I will be round to cut off your fingers). It’s a great lift for sauces, gravies and soups.

-

Basil oil - a real taste of the south of France

Chris Ward replied to a topic in France: Cooking & Baking

Yup, definitely if you're keeping them for any time at all. Mine usually goes within a day or two and it's always in the fridge. -

The late, great, English TV chef Keith Floyd used to cook with a bottle of wine, saying, "A glass for the recipe, a glass for me, a glass for the recipe, a glass for me...."

-

11: Making progress I get the whole idea of progressions; I understand why we do them and I even think I understand how to do them. But, to start with, I find it hard to actually write one down. A progression? It’s literally how you plan to progress through the day, in 5, 10 or 15 minute increments, all written down neatly on a proper form so your chef can write on it in red exactly where you’ve gone wrong. See, standing in the restaurant kitchen at 9 am it’s easy to see what needs doing first and why – square away the meat and put the roast in, make pastry for the tart cases, finish up with veg prep and the staff meal. Unless we’re roasting chicken for the staff, in which case we need to think of doing that at 1015 so the chicken will be roasted and rested by 1130. And if we’re making puff pastry that needs to be started first to allow the rests between turns. And of course if chef wants to cook the potatoes in their skins then that needs to be organised by 10 to give them time to roast and then cool a bit before peeling them. OK, OK. So it’s not obvious, unless you’re Chef and you’ve been doing this for 18 years and you don’t need to write anything down. But I do get how to do it: you start from the end and work back, starting with what you plan to serve at midday – for example - and then work backwards towards the start of the day. Whatever takes the longest to cook, do that first. Then work through your meat, fish, veg and patisserie in an order which allows you to keep your workstation clean and free of contaminants, doing everything of one type all in one go and then moving on to the next. Simples We get a choice of progression sheets at school; I find them both pretty easy to use, although School Chef reckons the one-column version is easier for us beginners – not so much chance of us trying to get ourselves to do two things at once, I suppose. So, progressions done today we’re supposed to be doing ‘Cotes de Porc Charcuterie’ – pork chops with a cooking juice and stock reduction and gherkin sauce – and ‘Oeufs pochés bragance’, poached eggs sitting in half a tomato covered with a béarnaise sauce. This is French Cooking As She Was Done By Escoffier, and don’t you forget it my lads. If it was good enough in 1905, it’s good enough in 2005 now shut up and make that bizarre sauce. On my progression form this means cut up the chops from the the whole ribs into portions of 4 ribs each, Frenching the bones - cleaning off the meat residue to make them look pretty - then do the veg prep while roasting the ribs, make the béarnaise while cooking the veg and reducing the cooking jus and poach the eggs when everything else is done and keeping warm for five minutes. But the pork hasn’t arrived so we start poaching eggs, which I think will be leathery in three hours time but there you go. Then the pork does arrive, but it’s not in whole ribs – they’ve been cut up into individual chops. Whilst they were still frozen. With a band saw. So, they’re not pretty and it’s a much too easy job to cut off what remains of the mangled vertebrae for us. In theory we: Remove the vertebra; de-nerve and de-fat; aplatir (tenderise by beating, apparently not the same thing as beating recalcitrant children), manchonner (oops, School Chef forgot to order the ‘paper condoms’, as Restaurant Chef calls the little hats you stick on rib bone ends) and reserve. Then we pan fry them, put them to one side to keep warm, recover the caramelised sugars from the pans and add some instant powdered stock to make a bit of a sauce, add in the julienned gherkins, monter au beurre et voilà , main course. Poaching the eggs is easier than scrambling them as we did last week; salted water just barely simmering, drop in the eggs one at a time one after the other, remove when cooked. When are they cooked? Harold McGee has an interesting idea about how if you get the percentage of salt exactly right in the water, you drop the eggs in and they rise to the surface at the moment they’re done. I’d love to tell you what that percentage is, but Chef’s borrowed my book at the moment (Restaurant Chef, that is). He doesn’t understand most of it and reckons McGee would make another fortune if he had it translated into French. After lunch we have Droit. Every week we, the students, ask each other “Is it Droit or Hygiène this week?”, then groan at the answer, whichever it is. We hate each one more than the other. This week: Business partners! So that’s banks, other financial partners, staff, the government, suppliers and clients. Who’s the most important? Duh. There are also ‘indirect’ partners – fashions, opinion leaders (journalists! The scum!)…it sort of goes on a bit, I think. Still. Back in the kitchen we go over ‘dégraissage et deglaçage’ – defatting and deglazing, or Getting The Most Out Of Your Cooked Meat. This is something I’ve never really thought about before. It’s something I’ve always automatically done with roasted meats – make a gravy with the bits that stick to the pan – but have almost never done with pan-fried meats, apart from making a mustard sauce in the pan in which I cook chicken breasts. And even then never really thought of it as the same sort of thing (reserve the chicken, deglaze with a large serving/soup spoon of mustard of your choice per portion, add two spoons of cream when the mustard bubbles, mix, season, serve). Choux pastry this afternoon, something else I’ve already practised in the restaurant. In fact, I know it quite well because RC is keen on it, and all our stagiaires have to know the recipe by heart (and so frequently stop by my plonge to ask me to remind them what it is): half the flour to the quantity of water, half that of butter, 16-20 eggs per litre depending – add the last one or four only if needed. I show School Chef the technique Restaurant Chef learned from the Patissier at the Martinez in Cannes for drying the détrempe of flour and water – with your sauteuse on the corner of the forneau, push the paste to the side of the pan furthest from you and then chop and drag it towards you in small pieces across the bottom of the pan. This may leave a crust on the bottom of the pan, but this doesn’t matter. When you’ve dragged it all towards you, turn it over and start again. It works better than just aimlessly smashing and stirring at it, ensuring that every bit gets an even chance of being dried out. We make Profiteroles with the Choux, filling them eventually with crème patissière – unfortunately, a good 10% or so are judges ‘unfit for service’ so we have to eat them ourselves. Ahem. The sacrifices we make… After that I got the bus home (Delphine, bless her, dropped me off at school at 0745 so I didn’t have to ride my bike, I’m still not well), made some pizza dough and then went straight to sleep. I made ham and mushroom pizzas when Delphine got home, we watched an episode of The West Wing (which I like lots) and I slept a solid 9 hours, only to wake up absolutely exhausted the next morning. Luckily I can go to work and spend 15 hours washing up for a bit of a rest. Lovely.

-

Basil oil - a real taste of the south of France

Chris Ward replied to a topic in France: Cooking & Baking

I'm still wondering what your 'high heat' applications are. I checked McGee, he has olive oil about the same as sunflower oil for frying. Perhaps, as I say, you have big castles and serfs to repulse with boiling oil. -

And yes, many patissiers go expat - see the Cronut in New York!

.jpg.05eb897150323539cf6b0726cd4ed9c4.jpg)