11. Seeking Ruby Murray

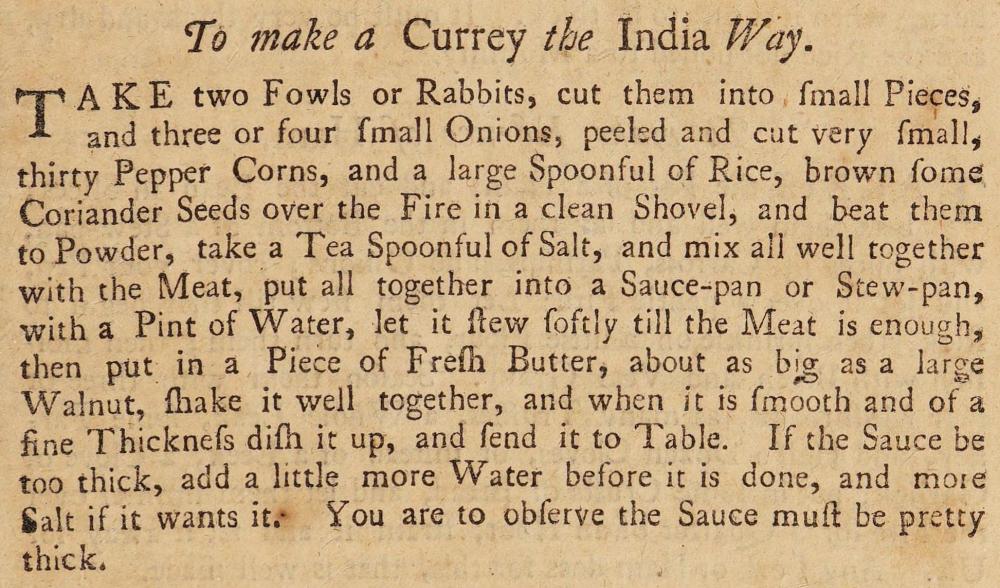

It is often assumed that “curry” came to Britain via the British Raj (1858 to 1947) or the earlier East India Company rule (1757-1857). However, the earliest printed English recipe for “Currey” appeared in Hannah Glasse’s highly successful The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy, first published in 1747. The word "curry" in English was long established prior to that, though, first being recorded in 1598.

Hannah Glasse – Art of Cooking - 1747

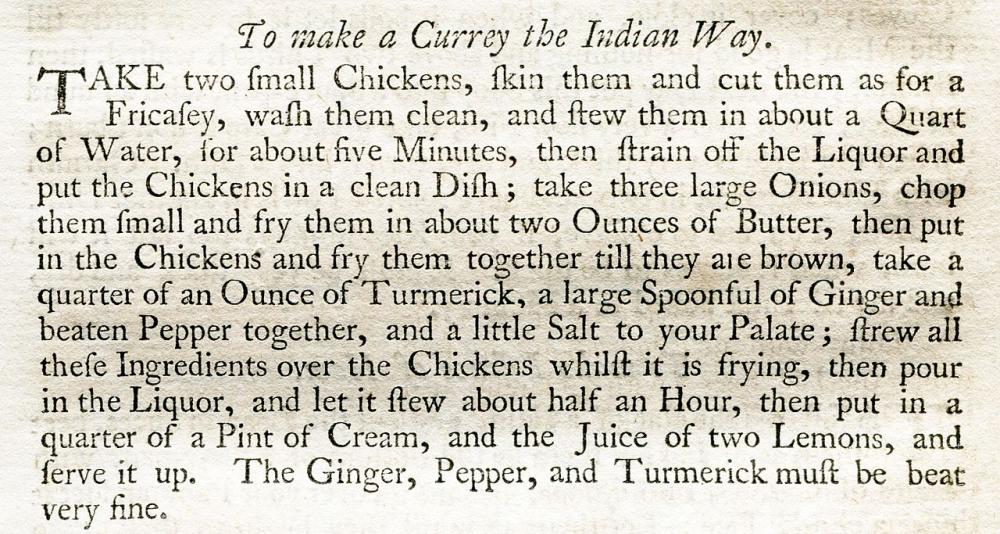

The dish may not be what we think of curry today, but with its liberal use of black peppercorns and coriander seed, we can see the beginnings of something more recognisable. Later editions updated the recipe to drop the rabbits and also include turmeric and ginger, as well as lemon and cream.

Hannah Glasse – Art of Cooking – 1774 edition

However, it was during the Company rule and later the British Raj, that more and more British personnel spent time in India and developed a taste for the local cuisine. On their return to Britain, they naturally wanted to continue eating their new-found favourites, or at least, a near approximation. Also, these people, while in India had their servants cook British dishes but with local spicing and other influences, leading to what is often described as Anglo-Indian cuisine. Instruction manuals for this food were printed and distributed in India, a well known example being Arthur Robert Kenney-Herbert’s Culinary Jottings for Madras, Or, A Treatise in Thirty Chapters on Reformed Cookery for Anglo-Indian Exiles from 1878. Catchy title, Arthur! Favourite dishes invented at the time include kedgeree, mulligatawny soup, seafood rissoles and a dish known as pish-pash, a soupy dish of rice with pieces of chopped meat, similar to congee and usually considered children’s food.

image - Simon Harriyott; licenced under CC BY 2.0

The first known “Indian” restaurant in Britain was the “Hindoostane Coffee House” in London, which appeared in 1809, but had failed by 1810, due to lack of interest. It did not sell the native food, but Anglo-Indian food, with the dishes reported as being “dressed with curry powder, rice, Cayenne, and the best spices of Arabia”. "Indian" food was also cooked at home from a similar date, as cookbooks of the time seem to attest. Few, if any, of these dishes remain on British menus today, and certainly not in “Indian” restaurants. One preparation that was hugely influential and remains popular to this day is chutney.

In the 1840s, thousands of east Indian sailors, known as lascars, were recruited by the East India Company, mainly in Bengal, the area now divided between the Indian state of West Bengal and the independent country of Bangladesh. Several jumped ship after arriving in British ports to escape ill-treatment at the hands of ship owners and disappeared into the cities to try to settle there. They were often met with hostility and racism, but some eventually found a sort of life, even marrying local women, despite opposition from politicians and church leaders. Most were bitterly poor and lived on charity, which earned them the reputation of being lazy and work-shy. The truth is few people would employ them.

Veeraswamy's, London - Image by Alex.muller - licenced under CC BY-SA 3.0

The oldest surviving Indian restaurant is Veeraswammy’s, opened on April 21st 1926 (the day Queen Elizabeth II was born), by Edward Palmer, a retired Anglo-Indian soldier and great-grandson of an English general and an Indian princess. Today, it is a Michelin star holding, upmarket venue serving authentic Indian food. A sample of dishes from their menu is here. Address: Mezzanine Floor, Victory House, 99 Regent Street, London W1B 4RS (entrance on Swallow Street) Tel. +44 20 7734 1041. Nearest Underground stations: Piccadilly or Oxford Circus.

In 1932, an Indian government survey of 'all Indians outside India' found a population of 7,128 Indians in the United Kingdom, including students, former lascars, and some professionals such as doctors. The resident Indian population of Birmingham was recorded at 100 which grew to around 1,000 by 1945. During WWII, a number of lascars served in the British army and many died. At the end of the war, a number of Indian soldiers, including former lascars, but also others who had also fought with the British forces, were demobbed in Britain and stayed.

In 1947 came India’s independence and the Partition which was the separation of what had been India into India and Pakistan, the latter being split into East and West Pakistan. This lead to internal violence and even more Indians and Pakistanis made their way to the UK. Like many immigrants before them a number of these new immigrants took to catering as a means to survive; initially serving up their own food to their fellow immigrants.

At that time curry in Britain was still stuck in the Hannah Glasse mode. Ersatz versions occasionally made their way to the British diner. In 1961, the British food company, Batchelor’s launched a type of processed “curry” known as Vesta. I remember these; they were weird. Basically dried, pre-cooked, sweet chicken in a vaguely spicy gravy and rice. Even when reconstituted according to the packet instructions, no one in India would have had a clue what it was supposed to be. (They also did “Chinese” dishes such as Chow Mien which would have left anyone in China baffled.) Batchelor’s is now owned by Premier Foods and appears to have dropped the Vesta chicken curry, although a beef version is still apparently available online. Why anyone would want it is a mystery.

It is made with these typically Indian ingredients: rice (57%), dried cooked beef (10%) (cooked beef, salt), maize starch, dried vegetables (8%) (onion, peas, carrot, green pepper, red pepper), dried glucose syrup, sugar, vegetable oils (sunflower palm), spices (ground fenugreek, ground coriander, ground turmeric, ground black pepper, ground cumin, ground celery seed, ground ginger, ground paprika, ground chilli, ground bay leaves), salt, tomato powder, yeast extract (containing barley), acid (citric acid), flavour enhancers (monosodium glutamate, disodium 5'-ribonucleotides).

In March 1971, the two geographically separated parts of Pakistan embarked upon a civil war which ended in the victory of East Pakistan in December of the same year and the renaming of East Pakistan to Bangladesh, as an independent state. This war and the earlier atrocities carried out by West Pakistan against the East which prompted the war, also led to a large number of people fleeing to the UK, mainly Bengalis. Once again many of these new settlers opened restaurants, initially aimed at their compatriots. The British people slowly started trying them out. I remember the first time I ate in an “Indian restaurant” in Britain. It was 1972 and my companion and I were the only non-South-Asian customers, as far as I could determine. I forget what we ate but it sure wasn’t Vesta.

So, it was around the early 1970s when “Indian” food really began to take off in Britain, mainly in restaurants owned and operated by Bengali immigrants. Today, the industry remains predominantly Bengali irrespective of what dishes appear on their menus. Indian cuisine, like neighbouring China’s is highly regional.

Today, “Indian” restaurants are everywhere in Britain. Even small remote villages are likely to have one, even if only for takeaway. Some are excellent, most are acceptable, a few less so – just like any other type of restaurant.

Of course, as time has gone by, many of the Bengali restaurateurs have modified their dishes to suit local preferences. They are in business to survive; not as some sort of museum curators. That said, the British public is increasingly looking for novelty and seeking out more and more regional cuisines.

In London, the area around Drummond Street in the Euston Station neighbourhood was known for its excellent southern Indian vegetarian food. The street was full of award winning restaurants, mainly run by Indian rather than Bangladeshi owners. Today, its future is in doubt, partly due to Covid, but more so because of developers building a new high-speed rail system that no one wants! Various campaigns are underway to rescue the street and area.

For more information on Drummond Street and its restaurants, this article is good, if somewhat out-of-date. I did contact friends in London to see if they had more recent information, but the pandemic is, as everywhere else, muddying thewaters. If I get more, I'll pass it on in due course.

For another, less-central version of the same cuisine I can recommend one restaurant well away from the tourist areas. Jai Krishna in Finsbury Park, north London is a popular Indian vegetarian restaurant and not only with vegetarians. I first visited in the 1980s when I lived nearby and made a point of visiting for lunch when I was in London in 2019. It hadn’t changed. Cheap but delicious food in simple but clean surroundings. 161 Stroud Green Rd, Finsbury Park, London N4 3PZ, United Kingdom Tel. +44 20 7272 1680. Menu here.

Image by me.

Thali - Papadam (not pictured), Mixed Vegetable Curry, Tarka Dal, Chickpea (Garbanzo) Curry, Boiled Rice, 3 Poori, Yogurt, Mango Chutney and Sweet. - Image by me.

Papri Chaat - Papri refers to crispy dough wafers served with potatoes, chillies, yoghurt and tamarind chutney, topped with pomegranate seeds - Image by me.

For more on the history of curry, I can recommend Lizzie Collingham's Curry: A Tale of Cooks and Conquerors (eG-friendly Amazon.com link). This is the American title. Elsewhere it is known as Curry - a biography.

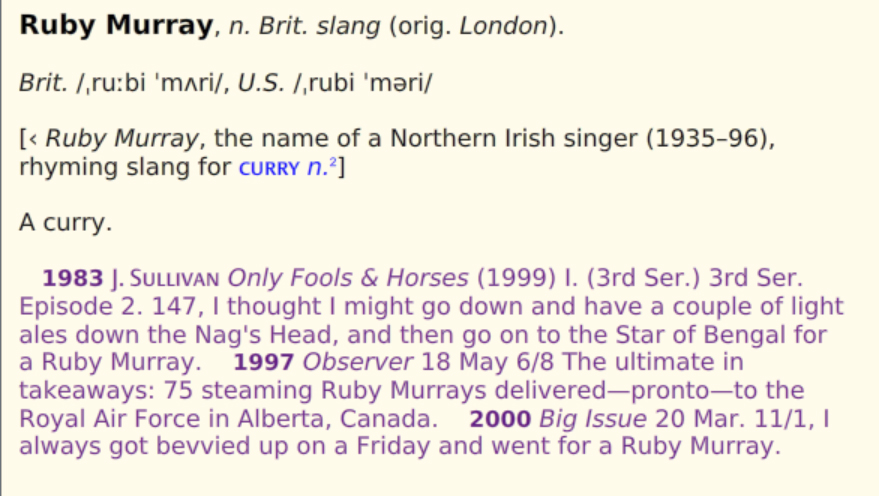

Finally, for this time, I hear some people asking who is Ruby Murray and did we find her? Here is an explanation.

More to come; much more.

.thumb.jpg.bbe60ba5e2c92a68324f7ad4d90e86dd.jpg)