-

Posts

1,728 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Store

Help Articles

Everything posted by Jonathan Day

-

I've printed this review to savour more slowly and carefully than the usual run down the laptop screen. Many thanks for taking the time to prepare it.

-

Santa Claus, the tooth fairy, a practical economist, and an old drunk are walking down the street together when they simultaneously spot a hundred dollar bill. Who gets it? The old drunk, of course; the other three are mythical creatures. Wasn't there a series of experiments in which students proved both to expect others to be more opportunistic and to behave more opportunistically themselves after taking an introductory economics course than before? Regardless of impunity, I wouldn't steal the money, and frankly I doubt that you would either. The economists I have known and collaborated with are scrupulously honest. But we should stop debating economics and economists and go back to food.

-

Thanks for your clarifying post, Tighe. I am a user of economic models, not an originator of them, so I concede right now your superior professional grip on the theory. Firms almost never pursue a simple profit objective; they worry about all sorts of other things as well: longevity of the business, private benefit for senior executives (e.g. social status), etc. Of course. But would you not agree that most models in incentive theory assume that effort has negative utility, which must be "compensated" for financially? The practical assumption is that most people are neither workaholics nor Mother Teresas. I don't think it is a misstatement of the Prisoner's Dilemma. Are you saying that a law-abiding society is an externality and that I refrain from theft simply because of long-run self-interest in maintaining this? You could follow the reasoning in Mancur Olson's work, e.g. the early chapters of Power and Prosperity in his model of stationary vs roving bandits. Or -- far simpler and more convincing in my view -- you could say that most people refrain from these activities because they think it is the right thing to do. See a related thread about the restaurant business as a "winner takes all" system.

-

The menu at Joy King Lau on Leicester Street is, as far as I can tell, 100% translated; if it's there in Chinese, it's also there in English. The food is pretty good, too.

-

There's actually a book, The Eater's Guide to Chinese Characters that uses a stroke-counting technique to help decode non-translated menu items. I suppose an analyst like Edward Said would say that Chinese and non-Chinese collaborate in a kind of orientalism, an attempt to preserve "the mysterious East" in the experience. My wife studied Chinese and Japanese and was once fairly adept at reading Chinese characters. We were in a restaurant where the English menu was of the sweet-and-sour-pork-egg-rolls variety, but the walls were festooned with strips of paper advertising Chinese dishes. She spotted one that looked good, and asked the waitress what it was. "That little birds," came the reply. We ordered it. They were roast quails, crunchy and delicious. We ordered another round. But writing "little birds" on the menu would be unlikely to attract most Western diners -- unless, of course, Cabrales had wandered in and decided that they were ortolans...

-

Tony, I can assure you that I have never been shy about raising a fuss when a restaurant did something inappropriate or overcharged for something. And I have, after lodging a complaint, walked out of more than one restaurant without paying for an item that was clearly not what it was described as, either by the waiter or by the menu. In this case, as I said, the overall experience and price were fine. I knew that items like fresh abalone or geoduck would be expensive. I chose not to ask in advance, and I chose not to make a fuss at the end. That has nothing to do with WASPishness. A little tolerance, please. I see off-menu specials printed up in Chinese far more often than in English. Could this have anything to do with restaurateurs' discomfort with written English?

-

Their scam-pricing is eerily precise: £19.50 was right at the edge of what I (and I suspect most customers) would pay without raising a fuss. Had it been much over £20 I would have demanded a reduction. In the UK I normally tip something like 10-12% in a place like this, where they indicate "service charge not included"; in this case, I rounded it to £95 so that they got £7.50, about 8.5%. In this case, the overall food and service were so good, the total price was reasonable, and the experience sufficiently pleasant (we didn't have to wait for a table, either, since the queue moved quickly) that I didn't raise a fuss about the price for the special.

-

The running time clock is a stroke of genius. I think I would have identified this as one of Whiting's writings even without knowing the author's name. Thanks, John.

-

Other branches of the Royal China have been written up elsewhere on eGullet, but we've been going to the Putney branch for some time now, mostly for weekend dimsam. For about the last year or so, the restaurant has offered several off-menu dishes as part of the dimsam service. Yesterday, we seemed to find more off-menu than on. And it was very good. My impression is that the staff size up a table based on the dishes it accepts; once a server succeeds in selling a particular off-menu special, the others try their luck. A few specialis were brought to the table on spec, a hand-carried version of the trolley, but most were simply recited. Once we ordered curried snails from the regular menu (delicious, if slightly rubbery), the offers arrived quickly. Among them: - geoduck clam, sliced paper-thin and served with what was described as "homemade soya sauce"; I have no idea whether the restaurant brewed the sauce itself, but it was slightly thicker than the usual, rich and rounded and nicely flavoured with chillis. The geoduck itself was fresh and very good (though, like the snails, also a bit rubbery). - steamed scallops in the shell, a special we have enjoyed before; these were very fresh, perfectly cooked, with a pleasing sweetness - baby octopus (this looked great, but by the time it arrived we had so much on the table that we turned it down) - spinach dumplings; we had ordered prawn and chive, but the waitress suggested these instead. Good suggestion. - coconut buns; sweet and slightly crunchy, with an eggy coconut custard filling But the best came last. We often order "turnip paste" (called "turnip cakes" in some restaurants), and we did this time. "How about spicy turnip paste?" asked the waitress. Sure, we said, why not? Where the turnip paste usually arrives in largish squares, this one came in much smaller ones (2cm) with a few egg shreds, some very fresh beansprouts, and just a hint of chilli. The flavours were deep and delicious, and the spicing and texture were perfect. We were tempted to order another dish of this. The on-menu dishes were fine, as well: nicely prepared lotus leaf rice, Peking duck, and several other dimsam items. Overall the price was reasonable (for London) especially given the quality of ingredients and preparation. However it is worth checking on the prices of the specials, which aren't announced at the time they are offered: the geoduck dish cost £19.50. Even with this, the bill for four adults and two children was £87, and this included half of a Peking duck.

-

Strictly speaking, actors maximise utility. However in most economic models, utility is equated to money, in part because it makes the maths simpler. Economic theory has little direct connection with the real world or real people. It assumes, for example, that people would rather not work (effort has "negative utility"). It assumes that people are mutually opportunistic (I would pick my best friend's pocket if I didn't fear that a policeman might be lurking around the corner). It is a heuristic device, a lens through which one can view behaviour. A useful lens for all that.

-

In practice it turns out that the utility functions (preferences) of consumers, owners and managers are easy to conceive but hard to model. Large firms suffer from the conflict between shareholders and managers; the latter typically have preferences for longevity as well as profitability, and senior managers receive substantial private benefit when a firm is larger -- corporate jets, meals at 3-star restaurants at company expense, etc. Your fungibility argument also explains why equity shareholders (as opposed to debtholders, employees, senior managers, customers) are typically the owners of large firms: this group is usually more homogeneous than any other, and its uniform preferences, for dividends, cash, growth, make for easier governance. The motivations and preferences of small business owners are very interesting and not all that well studied. Joel Podolny (a sociologist who has become adept at economic thinking) did a similar analysis of Silicon Valley start-up firms. My sense from posts in many eGullet threads is that restaurateurs are like winemakers: for many, the "love" motivation (the desire to run a place according to one's personal sensibilities and standards) is very strong, and that most independent restaurateurs are not particularly oriented toward profit. I would guess that food writers are in a similar situation. I can imagine a successful lawyer leaving a white shoe law firm to be a food writer; it's hard to imagine someone going in the opposite direction.

-

Classical economics works from the premise that each actor in an economic system, whether an individual or a firm, seeks to maximise financial profit. Firms, accordingly, produce the goods and services that customers demand. The real world only rarely resembles the world of the economist, that place “where a $10 bill is never found on the sidewalk, because someone has already stopped to pick it up.” Sometimes firms produce certain goods and services not because customers want them but because they enjoy producing them. Typically, these firms are privately held, since their owners are then free to pay for their production preferences by realising a lower than “optimal” rate of return. Fiona Scott Morton (an economist at Yale) and Joel Podolny (a sociologist now at Harvard) wrote an interesting paper on the motivation of owners in the California Wine Industry. Click here to view the paper, which is long but readable even if you skip the maths. Or if you are really in a hurry, here is an excerpt from the abstract: In other words: some winemakers, the profit-oriented owners, are in it for the money. Others, the utility-maximizers, are in the wine business “for love”; they enjoy making good wine, and don’t care that this leads to lower financial returns. Winemaking is therefore a difficult industry if you are in it purely for the money, since your competitors may be in it for love and thereby either underprice you or release more wine into the market than profit seeking logic would dictate. Scott Morton and Podolny suggest that similar results would be obtained if one studied opinion magazines, films, bars or horse racing. What about restaurants? I find the authors’ analysis and conclusions persuasive. They give further confirmation to the view (see this thread for discussion) that restaurants are “a bad business” and generally an inappropriate vehicle for a passive investor, i.e. one who derives no personal pleasure from owning a restaurant and is simply looking to make money. And what about food writing? It’s true that some talented people manage earn a living doing this, but are they not competing with those of us who do it for love, e.g. spending large amounts of time posting on eGullet (sometimes at great length) for rewards other than money?

-

Michael Ruhlman writes that Thomas Keller demands that favas be shucked and then peeled completely raw. They are then cooked, in a giant pot of furiously boiling water, salted like the ocean, a handful of beans to the litre. If the water even slows a bit when the beans are thrown in, the whole thing has to be thrown away and the prep cook ritually disembowelled.

-

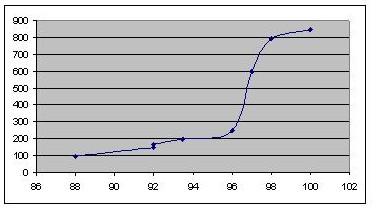

In FG's small data set, each additional RP point is worth on average about $62, but there is a large non-linearity between 96 and 97 points. The attached plots dollars (vertical) against points (horizontal).

-

A few thoughts on this interesting thread. (I had a great-aunt Tilly, by the way, and my daughter insisted on naming her hamster Tilly, even though I don't think I ever mentioned the aunt to her). Steven's "diminishing returns" idea makes a lot of sense to me. Economists speak of "hedonic price functions" that describe consumers' willingness to pay for specific characteristics of a product. For example, a bottle of wine might be characterised by the rating of its winery (r1) , a rating of the vintage year (r2), and perhaps some ratings of the region (r3) and varietal (r4), plus a Robert Parker rating (r5). Then, says the theory, a consumer will pay a price P that is a function of these characteristics: P = f(r1, r2, r3, r4, r5) and we can use statistical methods with names like "hedonic regression" to estimate the price impact of a change in r1, r2, r3, r4, r5...for example, a one point uptick in the Parker rating is worth $... Orley Aschenfelter, a Princeton economist, has done a lot of work specifically on wine ratings, and Robert and I hope to involve him in an eGullet roundtable at some point. On the personal side, I have to say that my preferences are very situational. Other things equal, I would choose the meal, simply because it offers more dimensions of pleasure than a bottle of wine (service, ambience, multiple courses, etc.). But if I had an evening to discuss the state of the world with a good friend, especially one who loved good wine, I think I would choose the wine over the dinner.

-

There's something of a gap between most home stick blenders (Braun, etc.) and the true professional models, which weigh a tonne and have huge motors. These will mix cement or purée nails into soup. But they are only suitable if you are doing several litres of whatever at a time. Hence the interest in the Bamix, which seems to sit between home and professional machines. I chatted briefly with Gordon Ramsay at a book launch; he said he used the Bamix constantly.

-

I have the Bamix "Gastro 200", the professional model. It's great, but it is designed for larger quantities and doesn't work in many applications where you have a small amount of liquid to be whipped or blended or frothed. The blending head is too large. I keep it right by the stove where it can be used without removing pots from burners. As other posters have noted, it doesn't really substitute for a cup blender, especially where foods are fibrous. But for most soups and sauces it works beautifully, and it's easy and fast to clean.

-

I believe that Brussels (EU HQ) can cajole and recommend, but that individual countries implement their own tax structures. A major issue in the EU right now, for example, is the wide spread in social taxes; this is leading a noticeable number of French small businesses to cross the channel and relocate to the UK.

-

I believe "Domestic Science" was another term for what was called "home economics" during the 1960s and 1970s. According to one source, For the complete reference, which includes pointers to articles, click here. For an example of a British Domestic Science exam from 1972, click here. The latter is interesting because it includes the menu plan written in response to the following question: For the first meal, the examinee prepared: sausage rolls (this included preparation of rough puff pastry) salad (lettuce, tomatoes, watercress, cucumber, hard boiled eggs, spring onions, beetroot) fresh fruit salad (apples, oranges, banana, mixed grapes) cold custard (made with custard powder) And for the second: fish pie (potatoes, haddock fillet, onion, streaky bacon, tomato) carrots brussels sprouts (but this dish was crossed off the exam paper) apple cornflake crunch (cooking apples, sugar, butter, cornflakes, evaporated milk, golden syrup) The "theory" section of the exam had questions like the following

-

I have had the same experience both in Britain, and even more recently in Russia: three of us were travelling from St Petersburg to Moscow on the night sleeper train (the St Petersburg airport had closed because of the summit). As we settled into our compartments, a young woman came through the carriage, carrying a basket with bottles of beer. She didn't speak English, but she could say "Stella", and "Bud". We asked the price, and she took out a notepad. 150 roubles (about US$5) a bottle. No, we said, too much. OK, she said, and scribbled on the notepad: 30 roubles for a Stella, 40 for a Bud. We took 3 bottles (total 110 roubles) and handed her 200 roubles. She then took out a calculator and carefully worked out the change: 200 - 110 = 90. So much for Russian proficiency in mathematics...

-

Actually, I don't think that's an accurate summary of the recent argument. One proposition was, in essence, "I didn't enjoy my meal at El Bulli, therefore it is a bad restaurant", i.e. one that delivers food that most people would agree doesn't taste good, whether or not it is intellectually interesting. (I'll skip the comments from those who have not dined at El Bulli). The second proposition was, "Granted that you didn't enjoy your meal at El Bulli. This could have happened for more than one reason. It could be that El Bulli is a bad restaurant in the sense outlined above. It could be that your palate was not up to appreciating the restaurant, or that you fell into the trap of "tasting with the mind instead of the mouth" because a description of a dish or its appearance was off-putting. Or it could be that the restaurant was having an off night." I'll add that there is a thin line between the third possibility and the first. A great restaurant should only very rarely have an "off night". If this happens with any frequency at all, El Bulli deserves to lose its reputation and its associated stars.

-

But our ideas about what tastes good can develop over time. For my children, as with most children, the set of things that taste good started out very small. As they have grown, they have begun to embrace new tastes: complex cheeses, sauces, olives, and the like. They have grown from a focus on the sweet to accepting and appreciating tastes with a bitter component like dark chocolate. Adults can also learn to broaden their ideas about what tastes good. Some things are genuinely disgusting, at least to most people, and this does not change with time. Other tastes (or taste-texture pairings) seem odd at first, but we learn to appreciate them with experience and a bit of patience. It is easy to caricature Adria as presenting dishes that are "not food" or that taste bad, but that, if your IQ is high enough, you somehow manage to enjoy. This is false. He does challenge our assumptions about what goes with what, and about what form foods come in. But these assumptions deserve to be challenged, just as my daughter's learning to enjoy pasta with something other than ketchup is an important step in the development of her sensibilities.

-

This one has been discussed at great length on eGullet, mostly on the "General" forum. Start here for an example, but this is hardly the only place that it has come up.

-

It is equally pretentious to dismiss foams simply because they are overly popular in some circles. The point is to use them where they enhance a dish, and nowhere else. Both the "pro" and "anti" positions seem more religious than gastronomic.

-

And let me add that I (and many other diners the night we dined) found the food not only intriguing but also delicious. I am prepared to believe that the restaurant may have had an "off" night when Matthew visited; the wine service as described seems completely at odds with the service we received which was as good as any wine service I can recall. If Adria's dishes were intellectually interesting but otherwise consistently unpalatable, I might join in the critique. But that isn't how I experienced them. I would add that for some diners there may be a "mind over palate" effect (a felicitous expression coined by Robert Brown) at work. The dishes at El Bulli do look strange, and they consistently violate our expectations about what will look like and taste like what. Some people look at a dish or read its description and mentally rule it out, so that no matter how delicious it would be if they tasted it without first seeing it or reading about it, they cannot tolerate it. Matthew dismissed the orange peel tempura, writing "my God it was pieces of orange peel fried in batter". We didn't have an orange peel tempura, but we did have a lemon peel tempura, which was superb: light and crisp, a perfect foil for the spiced apple it was served with. Perhaps Matthew's didn't measure up. It sounds as though his dinner, and the wine service especially, were unacceptable. But those who have not dined there should not assume that this is consistently true of El Bulli. It isn't.