-

Posts

11,151 -

Joined

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Store

Help Articles

Posts posted by slkinsey

-

-

What I find interesting is, even with a 3oz shot you have a hard time filling a standard cocktail glass. Most I have are 8oz or more with the Riedel 4.5oz a near perfect exception.

Something akin to the Libby Embassy 4.5 ounce coupe seems to be the standard in NYC. I don't have any difficulty filling this appropriately full with a shaken cocktail that starts out at 3.0 - 3.5 ounces. Around 3 ounces is the standard American pre-dilution volume in cocktail bars, with some rare exceptions. This is why, for example, Pegu Club and some other bars have the practice of decanting half of large volume Martinis into a little glass caraffe that sits in a bowl of crushed ice: (1) because they don't want the oversized drink to get warm before it's finished; and (2) because the drink won't fit into any of their glassware.

Keep in mind that with a V-shape or coupe shape, there is likely to be little visual difference between a 3.6 ounce pour (20% dilution on 3 ounces of booze) and a 4.25 ounce pour (25% dilution on 3.5 ounces of booze) in the glass. The larger pour will appear to fill the glass all the way to the top whereas the smaller pour will have a tiny collar.

His glass doesn't look tiny yet full in the video even before adding the ice. In his book he is saying that the prolonged hard shake doesn't water the cocktail down, which to me means the aeration must be adding the volume.I'll get into that later, but suffice it to say that I don't agree with his assessment as to increased dilution with a prolongued hard shake. It also seems possible that his glassware is smaller. Certainly the glassware he's using is far smaller than 8 ounce birdbaths. I have had no trouble filling my standard Libbey coupes appropriately using a hard shake with 2 - 2.5 ounces of ingredients to start. Some of that is in the form of floating ice chips, and some is in the form of added dilution. I don't believe aeration alone (as opposed to stable foaming as when cream and/or eggs are used) could possibly be responsible for the increased volume I am observing.

Also I can not believe they use 2oz on stirred drinks, lets say a Manhattan. It would look funny.Flipping through the book, it's hard to tell what the volumes are exactly, because most of the cocktails are listed in "parts" rather than absolute volumes. That said, I am reliably told that 2 ounces is the standard cocktail pour in Japan. More to the point, all the recipes in the book that do specify volumes come out to 2 ounces plus one teaspoon or less. This is important to understand because many of his recipes call for something like: 4 parts scotch, 1 part Cointreau, 1 part fresh lime juice, 1 teaspoon blue curacao. Needless to say, if you don't have an idea as to the total volume of the other three ingredients, the 1 teaspoon of blue curacao will not have the desired effect.

-

I thought it was good, but not appreciably better than cocktails I've had at US cocktail bars. I'm normally a "fine-strain the ice shards out" kind of guy, but they didn't really bother me here.

It's interesting to me that tasting reactions range from "the recipes were a time-warp from 1987 and the drinks were watery" to "pretty good" to "it was hands-down the greatest cocktail experience of my life."

. . . I balked at paying 1900 yen for my first choice, a Sidecar. Indeed, the overwhelming impression was just how far outside my budget it was, which is why I didn't delve any further into the menu there or the cocktail scene in Japan more widely.One of my overwhelming impressions from the Japanese techniques seminar was that many of the elements of Uyeda's "Japanese way of the cocktail" -- the choreographed bottle opening, slow ritualistic preparation of Mizuwari, etc. -- are really only tenable in small bars that charge 20 bucks or more for a 2 ounce cocktail.

-

So... what did you order and what was your impression?

I've talked to a number of cocktail community friends at a variety of ages, areas and levels of expertise who have had cocktails around Japan and also specifically at Tender. Their reactions vary widely.

-

Kohai can answer that question better than I, but I asked him the same thing. I believe he said that Tender seats around 30 people. So most of them don't sit at the bar. That, in my opinion, seriously limits the extent to which customers who are not at the bar can benefit from the "total experience" factors that Uyeda discussed in the "Japanese way of the cocktail." It's a bit like sitting at a table in a sushi bar... or any bar, really. My wife isn't a huge fan of sitting at the bar when we go out for cocktails. But IMO if you're not at the bar, you're missing out on 50% of the experience. On the other hand, at a bar like Tender I am given to understand that a not insignificant percentage of the customer base is comprised of older gentlemen who want to savor an expensive whiskey and water for a couple of hours and don't really need to sit at the bar for that.

-

Shaking, says Uyeda, is to be used instead of shaking [sic] when the ingredients are dissimilar and more difficult to combine. This mostly includes juices, cream and egg. The primary goal of shaking the cocktail is to aerate the liquid and form tiny bubbles in the liquid. Chilling will take care of itself, so mixing is the primary goal.

Emphasis added.

Is the primary goal of shaking mixing or aeration, or are they coequal?

Secondly, if aeration is a good, why would you ever stir? (Stirring, as previously described, combines with the least aeration possible.) Or, is aeration only a good in cases where juices/cream/eggs are involved? In which case, is it possible that there would be a better way to make a drink that involved aerating those components that benefit from such treatment before incorporating those that do not in a less violent way?

Clearly some of this was written in haste and not particularly well proof-read. Of course it should say that shaking is to be used "instead of stirring" when the ingredients are dissimilar and more difficult to combine. If I were to rewrite this more clearly, I think it would be more accurate to say that "mixing is the primary goal of shaking, and aeration is the primary goal of this shaking technique."

In contrasting shaking to stirring, according to Uyeda's explanation, since the ingredients for stirred cocktails are easily combined and because the physical limitations of stirring mean that you can't use nearly as much ice as you can in shaking, the task of chilling the drink becomes the primary goal, and combining/mixing the ingredients largely takes care of itself due to the nature of the ingredients used. The opposite is true when you are shaking.

As far as I can tell from my notes, in this conception, mixing and aeration are largely part of the same thing. The point is that you have some ingredients that don't easily combine, and by moving them around in a way that introduces a lot of aeration and small bubbles, you are able to mix these otherwise not-very-mixable ingredients into a whole. The aeration is part of what lets you mix these ingredients. An element of the hard shake paradigm is the idea that the introduction of these tiny bubbles into the liquid has certain special effects. But that's something I haven't got to yet.

To get to your next question: Uyeda says that shaking is useful when using ingredients that have different specific gravities or that are otherwise difficult to combine, such as when juices, cream and/or eggs are used. It follows, then, that aeration is good and desirable in these situations, but not in others.

The philosophy behind the stark differentiation between the two conceptions (maximum aeration in shaking and minimum aeration in stirring) is to have a complete commitment to whichever technique you are using. The stir should be as stir-like as possible, maximizing the unique qualities of stirring, and the shake should be as shake-like as possible, maximizing the unique qualities of shaking. This makes sense to me: A hastily stirred or lazily shaken cocktail is nothing special. Go all the way.

As to whether there might be a better way of doing these things... that's open to interpretation, and something I will touch upon later. Suffice it to say that I will provide some examples as to how extremely different Western techniques can create an equivalent or perhaps superior result. Uyeda might suggest that this question in and of itself reflects the Western results-driven paradigm rather than the Japanese process-driven paradigm. There are certainly different ways of doing all these things, and also different ideas as to the effects desired. To make an obvious example, dry shaking is a highly effective way to get good aeration and foaming in egg white drinks. Or, to take it to the extreme, instead of shaking one could simply keep all the ingredients chilled to the desired temperature, add water to hit the desired degree of dilution, insert a micro-fine aeration stone into the liquid, and blast through some high-pressure air. That would give you far more aeration than would be possible with any shaking method. Similarly, "stirred" cocktails could easily be produced by measuring pre-chilled spirits and water into a prepared glass and giving it the briefest of stirs to combine. Whether this sort of thing is desirable or not . . . who is to say? Certainly it's not desirable to me.

Dry-shaking, for example, is probably something that would never enter Uyeda's mind. Since it is, or seems like it should be possible to create the perfect frothed egg white drink by hard shaking with ice, then the focus would be on refining the hard shake technique for egg whites to such a degree that it turns out perfect... even if it might be easier to get a peak result by dry shaking everything first. I suppose that this kind of Japanese process-driven paradigm is related to the same mind-set that makes so many of us work and work and work to refine the perfect way of roasting a whole turkey so that the leg meat and breast meat are both perfectly cooked, even though we know that it is easier to do these things when the turkey is broken down and the dark and white meat cooked separately.

At this point, I am mostly trying to present Uyeda's ideas about these things without too much criticism. Dipping my toes into that water, I will say that I am not convinced that the whole "aeration versus no-aeration" thing makes a whole lot of difference after the drink has sat in the glass for more than around 60 seconds at most. I have my doubts as to whether anyone could tell the difference bewteen a 60 second old Martini that had been shaken and one that had been stirred. Indeed, it may not be possible to reliably tell the difference between 5 second old stirred and shaken Martinis blindfolded. On the other hand, I think Uyeda is correct about the utility of shaking with respect to drinks compounded of difficult-to-mix ingredients. It shouldn't be too difficult to tell the difference between a stirred Sidecar and a shaken one. On the other hand, there is nothing that beats those first few silky sips from a stirred cocktail. Perhaps this is all an argument for smaller cocktails -- so that you finish them while they still display the characteristicts of the mixing method. For what it's worth, the standard Japanese pour is only 2 ounces -- around 1/3 smaller than the standard cocktail pour in America. On the other hand, Japanese imbibers are said to take a long time lingering over their cocktails. This has never made much sense to me unless it's a long drink. I rather agree with Harry Craddock: Drink it quickly, while it's still laughing at you.

-

Now on to the hard shake. I'll begin by describing the technique, then set forth Uyeda's claims and thinking with respect to the technique, then add some of my own thoughts, reactions and observations. For those who have familiarized themselves with the various options available in mainstream Japanese shaking as described above, the hard shake technique may be somewhat anticlimactic. It is fundamentally the same as a mainstream Japanese shake, with one elaboration and one new element.

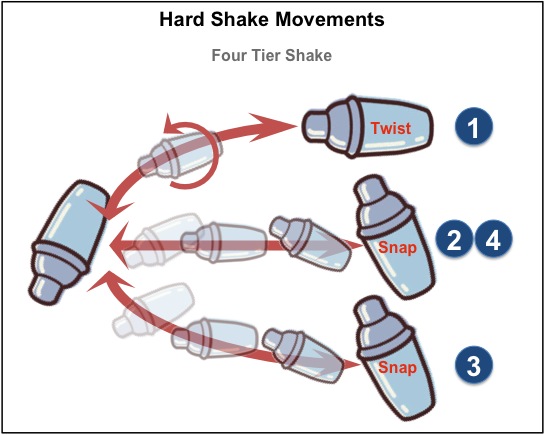

First, for what is the same: The hard shake is a horiztal shake with snap, and the shaker is held at an angle relative to the direction of movement so that the ice doesn't slam into the bottom of the shaker and crack.

Second, for what is an elaboration: The hard shake is a three-tier, four beat shake rather than being a two-tier, two-beat shake. What does this mean? In the two-tier shake described above, there is one throw to the top tier (beat #1) and one throw to the bottom tier (beat #2), and then back to the beginning. In the hard shake, there is a top tier, a bottom tier and a middle tier. So the movement is: one throw to the top tier (beat #1), one throw to the middle tier (beat #2), one throw to the bottom tier (beat #3), the final throw to the middle tier (beat #4), and then back to the beginning. The shaking sound should be smooth and uninterrupted, and there is an emphasis on the first beat (just as there is with the first beat of a 4-beat bar of music). So the sound should be something like: "SHUCK-a, shuck-a, shuck-a, shuck-a, SHUCK-a, shuck-a, shuck-a, shuck-a, SHUCK-a, shuck-a, shuck-a, shuck-a, (etc.)." There is usually a medium tempo start accelerating to "as fast as possible" by the beginning of the second sequence, and the final sequence usually decelerates to a gentle stop.

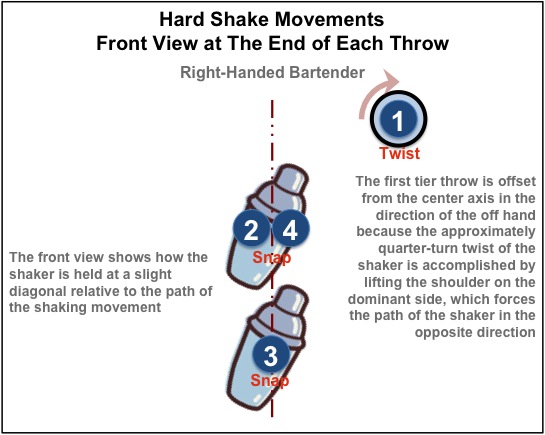

Finally, for the innovation: The first throw is in the sequence is not snapped, but rather given a 1/4 twist on its longitudinal axis. This is accomplished by raising the dominant-side shoulder and elbow to rotate the shaker in the opposite direction. This movement also has the effect of changing the motion of the first throw. Whereas the other three throws in the sequence are more or less straight out from the center of the body, the twist maneuver pushes the "twist throw" over slightly to the off side.

Side View

Front View Facing Towards the Bartender

One thing I noticed from watching Uyeda is that there is not all that much difference in the height of the various tiers. In some other demonstrations of this technique, the top tier almost seems to be head-height with the bottom throw being somewhere in the vicinity of the belt. With Uyeda, everything seemed to be between shoulder height and sternum height -- a range of about 12 inches.

-

"I laughed. I cried. It was bettah than Sripraphai!"

-

That effect has got to be pretty negligible. Taking the lid off would accelerate cooling by orders of magnitude compared to using a copper lid. The function of a lid, after all, is to keep heat in -- not let it out.

-

There's no particular reason for having copper lids, other than that they match visually and can become part of the presentation, but if you want to cool a pot in an ice bath but leave it covered, the copper lid will draw off some more heat.

Er... not really. Not unless the pot is submerged. And in contact with the internal contents.

-

Definitely not brass for the handles ... to conductive.

I don't know about people who actually cook for a living, but for every hour I work with a copper pot in my home, I spend ten looking at it hanging from the ceiling.

Brass and copper are beautiful together. I know it's superficial but when it comes to handles, I'll take appearance over heat transfer coefficient.

Also not heavy enough, IMO, to balance the pan properly. I am not aware of any "long handle" (as opposed to loop handle) copper pans at the full heavy gauge that have a brass handle. And you won't find brass handles approaching the thickness of the traditional iron handles. Brass handles are usually found on 1.6mm gauge copper pans intended for table service and not for cooking (except perhaps for the occasional flambé-type finish tableside). Personally, I think the iron handles look pretty good anyway.

-

It retails for about $40 for a 750, which seems fair for what it is.

For what it is? It's aged one year. One! For 40 dollars.

I mean, sure it's good. (80% rye, by the way). But 40 bucks is not a "mixing and everyday drinking" spirit, and it seems comparable to other whiskies priced at a bit more than half as much. Okay, bump it up a bit for dumping it into a sherry barrel for the last three months (whence the color and body comes). But too many distilleries are coming out with $40-$60 spirits. They are rarely worth that price given the age and quality versus what's already available at a substantially lower price point. Is this stuff really that much better than Old Overholt? Or Rittenhouse? It's a bit like the Cornelius Applejack, which at $40 a bottle doesn't approach the quality of Laird's bonded. So why is it double the price? I can spot a company 5 or even 10 bucks due to the economies of scale. But who mixes regularly with $40 spirits? Not me. That's what I like so much about Redemption Rye. Finally, a new rye whiskey that can be a staple rather than a treat.

-

54.5C times 1:40 seems like an awfully short time and an awfully low temperature for something with as much connective tissue as a lamb shank.

-

To continue, the first day closed out with a section on Japanese shaking techniques and philosophies. Uyeda was emphatic that this first session was not the hard shake, but rather a discourse on generalzied Japanese shaking. However, as noted above, the extent to which Uyeda has a basis on which to make generalized statements on Japanese techniques is anything but clear considering that he doesn't exactly make the rounds. Those with a better understanding of the Japanese bartending scene may be able to contribute more information here where my notes are not entirely accurate...

Shaking, says Uyeda, is to be used instead of shaking when the ingredients are dissimilar and more difficult to combine. This mostly includes juices, cream and egg. The primary goal of shaking the cocktail is to aerate the liquid and form tiny bubbles in the liquid. Chilling will take care of itself, so mixing is the primary goal. Unlike stirring, where you only want to use as much ice as will contact the liquid, with shaking the goal is to use lots of ice. Indeed, use as much ice as you possibly can, because the shaking method moves the liquid around in the shaker to touch all of the ice and therefore every piece of ice can participate in chilling and aerating the liquid.

Ice is important. As with stirring, Uyeda stressed the importance of using a mixture of ice cubes and different sized pieces of ice that has been cracked from clear block ice in order to minimize the voids inside the shaker. Also, as with stirring, the process begins with "washing" the ice with water and shaking out the excess.

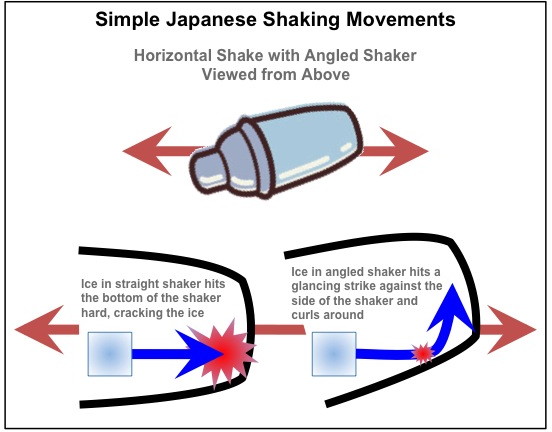

Now we come to some of the most notable differences between Japanese style shaking and Western style shaking. First, almost every Japanese bartender uses a three-piece cobbler shaker rather than the usual Boston shaker sets used by Western bartenders. Among a number of differences, using a cobbler shaker minimizes the headspace in the shaker (the area inside the shaker that is not filled with ice). A smaller headspace means that there is a smaller amount of air trapped inside the shaker during shaking, which Uyeda says is good for aeration. I note myself that a smaller headspace and a tightly packed shaker also has the effect of limiting the extent to which the ice can move around during shaking and the relative violence of any collisions inside the shaker. This is important because one thing Uyeda streses is the importance of considering the movement of the ice inside the shaker: you want to move the ice as much as possible, and you want to move in in a way that minimizes any hard collisions against the bottom of the shaker. I am not convinced that the ice moves all that much with this technique. Rather, I think it moves in a kind of cocktail shaking

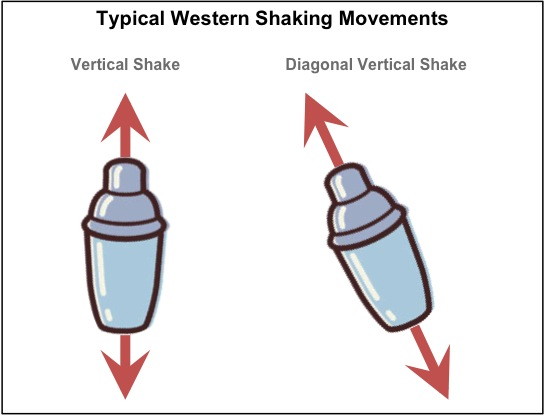

due to the fact that there is very little room for it to move around. Uyeda does admit that he has no idea whether or not his idea of what the ice is doing in the shaker actually happens, but rather that this is how he likes to conceptualize it.Other than the shaker, there are some other notable differences between typical Japanese and typical Western shaking techniques. Most Western shaking is done with the shaker in a vertical position and the fundamental shaking movement being up-and-down (or slightly angled). This is often done one handed if the bartender's hands are large and strong enough to grip the shaker securely:

Japanese shaking, on the other hand, is done in a side-by-side motion with the shaker held in a horizontal position and using both hands always. The dominant hand is on the cap end of the shaker, with the thumb on the cap, the index finger resting on the top and the middle finger on the bottom of the shoulder of the strainer piece, and the other fingers grasping the body of the strainer like a football. The off hand is held fingers together and palm up, with the last two joints of the fingers curled up around the end of the shaker and the body of the shaker resting in the slightly cupped palm of the off hand. The dominant hand is on top of the shaker and the off hand is below the shaker. The cap end of the shaker is facing the chest, and the shaking movement is in a push-pull motion away from the chest on a horizontal plane.

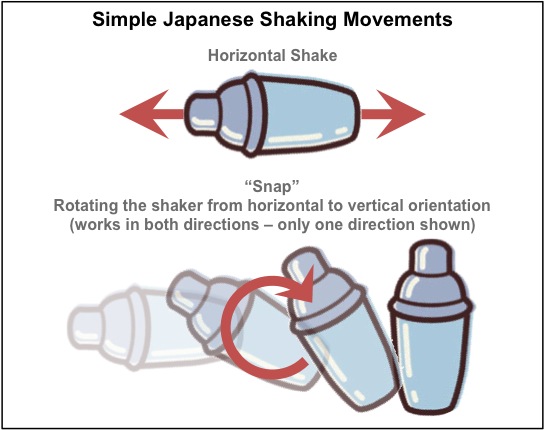

There is also a "snap" motion that can be made, where the shaker is rotated up to a vertical position with the cap facing up, and then back down to a vertical postition where the cap is facing down (I have only illustrated one half of the movement, but I think it's pretty easy to get the general idea).

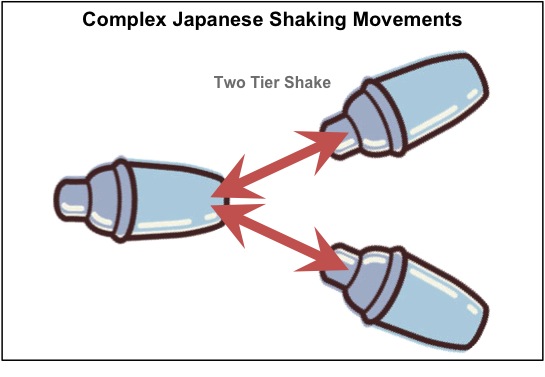

Of course, hardly anyone does a simple horizontal push-pull shake. According to Uyeda, the most commonly taught and practiced shake in Japan is a "two-tier shake" where one "throw" of the shaker does diagonally up a bit, the next "throw" of the shaker goes down diagonally a bit, and so on back-and-forth between the two tiers of the shake:

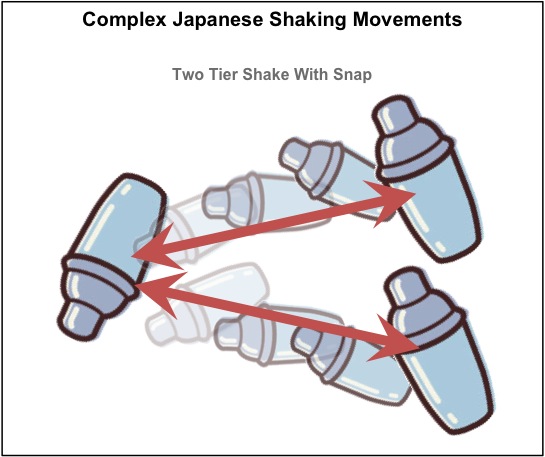

Most shaking techniques also incorporate a certain amount of "snap" as well in the two-tier shake, so you end up with something like this:

Different bartenders operating under different shaking disciplines and paradigms may emphasize various elements of the basic push-pull, snap and tier techniques, some to such an extent that the other elements may hardly figure. For example, Uyeda spoke of a bar that was said to shake cocktails with a motion that was almost exclusively snap.

The shaker is often held at a slight angle to the direction of movement in order to minimize the effect of the ice slamming against the bottom of the shaker and breaking off large pieces. The idea is that the ice will sort of slide down against the curved side wall of the shaker and curl around the bottom in a kind of "rolling motion."

-

Some good news may be on the horizon in that respect. I had the opportunity yesterday to sample some Redemption Rye. This is a new brand which will be hitting the market within a few months. It's made with a 95% rye mash bill, in contrast to the usual 51% or so, resulting in a uniquely spicy rye character that is not unlike drinking an alcoholic glass of rye bread. I believe the plan is to release a bottling at 92 proof and a barrel proof. The 92 proof bottling should sell for around 25 bucks! Right now it's pretty young, clocking in at around 2.5 years. But I think there's the sense that they might as well start releasing some of it now, but continue holding some back to see how it develops with age and eventually figure out the sweet spot. So it will likely evolve somewhat over the next half-decade or more. In the meantime, they get to put the product out there, build some awareness, and make some money off their efforts without going the usual route of starting off with a vodka. I thought it was very promising, and definitely plan to purchase some when it is released. The unusually strong rye character will make for some very interesting mixing. I was also happy to hear that they are committed to offering a product at a price point appropriate for mixing and casual drinking rather than the usual route of releasing a super-expensive extra-age spirit.

-

If the price were reasonable, a 2.5mm copper body coated inside and out with a very thin layer of tungsten carbide might be very interesting...

I guess the idea would be to find whatever material you could use that would be the hardest, toughest material you could use in the thinnest possible layer that would also have reasonably good thermal properties. I would imagine that, even if the layer of the nonreactive material were very thin, having very poor thermal properties would reduce the performance of the pan. For example, enameled cast iron is far inferior to regular cast iron at browning meats, etc.

-

Interesting

So... what durable nonreactive material do you contemplate plating the copper with? And in what thickness? Obviously, the point would be to plate the copper in the thinnest possible layer of durable nonreactive material so that you get the thermal benefits of copper and the reactivity benefits of the other stuff. The thicker the plating has to be, the more the thermal performance of the cookware is diminished.

As I said, anything that could give the thermal performance of 2.5mm copper but be 100% nonreactive and dishwasher safe would be highly desirable. Needless to say, the plating material would need to be able to withstand hard use, and also be a reasonably good cooking surface (although it's hard to know how anything could be more naturally sticky than stainless steel).

-

What Shalmanese said. The marketing claim that a burner can maintain 130F in all conditions is bullcrap unless the burner itself is at 130F (which is impossible). Otherwise, it will always depend on the thermal characteristics of what is being heated.

-

Thank you for your responses.

Clarification - I'm not looking for advice on buying copper pans, I want to make them commercially (on a very small scale) and I want to know what you guys would like to see.

So, go nuts.

What are your manufacturing capabilities? Or, rather, what cladding materials do you think you will be able to use in combination with the copper? Just about every "artisinal" producer of copper cookware does the traditional tin lining, because they don't have the capability to do stainless.

-

The shapes and sizes you want will depend on what cooking you want to do. In my opinion, there are better design and materials choices for many cooking tasks (e.g., heavy stainless steel with a thick aluminum or copper base is better for a stockpot).

Which tasks/pans would you say this is the ideal material for? Frying pan and sauce pan?

Real frying pan (i.e., with widely sloping and short sides, not one of these "frypans" that is the same basic shape as a saute pan with curved sides)

Sauce pans that will be used for actual sauce making (i.e., not the kind used for boiling thin liquids, steaming vegetables, etc.)

Reduction pans

Large saute pans or large sauteuses evasee (not so much for the task of sauteing, which I think is usually done better with an extra-thick disk bottom design, but rather because straight gauge gives some added versatility)

-

Upon re-reading the OP, maybe you're thinking of manufacturing these pans? That's a tough one. It's hard to beat a stainless lining, and as far as I know it is extremely difficult to bond copper to stainless. It's hard to imagine why someone would prefer a different pan (especially an expensive one) over the currently available stainless-lined brands unless you were somehow able to plate the copper with a very thin layer of something equally durable and nonreactive.

I guess my dream pan would be something like 2.5mm of copper fully clad both externally and internally with a 0.1mm layer of stainless steel, in the traditional shapes, and having a heavy stainless steel handle. The idea being to have all the benefits of heavy copper in the traditional designs with the added benefit of being dishwasher-safe.

Well-fitting heavy stainless lids are still the best option, IMO. No one who actually uses his copper cookware likes those copper lids.

-

There really is not much question here. If you are talking about copper cookware that will be used for cooking, as opposed to simply display pieces for plating, then what you want is 2.5mm stainless-lined copper with an iron handle. Period.

They do make stainless lined copper cookware with a stainless steel handle, but it's not clear that there is much benefit to be gained from having a stainless steel handle (it will take longer to get hot, but on the other hand it will stay hot a lot longer compared to iron) and anyway the stainless lined copper cookware with a stainless steel handle is only 2.0mm thick.

As for the lids... you just want one that fits and is easy to clean. Most of the copper cookware manufacturers do produce a stainless lined copper lid, but there is absolutely no functional point to having the lids made of this material and they are a needless hassle to keep clean. Just buy a reasonably sturdy stainless lid in the appropriate diameter.

The three companies most known for making stainless lined heavy copper are, in alphabetical order, Bourgeat, Falk Culinair and Mauviel. Other than some design details such as handle positioning, size of the rivets, polished versus brushed external and interior surfaces, rolled versus straight lip, and some minor differences in shape, the stainless lined heavy copper produced by these three manufacturers is functionally identical (indeed, they are all made from the copper-stainless bimetal produced by Falk Culinair). Which brand you prefer comes down to personal preference as to the above-mentioned details, and budget (there can be notable differences in price). I happen to prefer Falk Culinair, but YMMV.

The shapes and sizes you want will depend on what cooking you want to do. In my opinion, there are better design and materials choices for many cooking tasks (e.g., heavy stainless steel with a thick aluminum or copper base is better for a stockpot).

-

At home I have always liked stirred cocktails with pretty much 100% hand-cracked ice from the freezer and no big pieces, using a frozen heavy glass mixing vessel. I feel like this allows me to get the coldest result and the right amount of dilution. Hand-cracked ice, of course, also leaves very little in the way of void spaces between pieces, so the ratio of ice to liquid is as high as possible. I suspect that working bars using 0C ice and a less thoroughly-chilled mixing vessel need to include more large pieces in order to avoid over-dilution.

-

I don't think that the bols products are better quality in Europe.

It is a fact that the American Bols liqueurs are not made at the same place or using the same ingredients as the Bols liqueurs available elsewhere. Many Americans are surprised to learn that Bols liqueurs are held in high regard by non-Americans, given the overall low quality of the product sold in the United States.

ETA: To be clear, the Bols liqueurs sold in the US are not produced by Bols at all, but rather are produced in North America by a different company under license from the European company. The American producers, in other words, purchased the rights to the brand name in the US (they probably also pay for a non-compete in this market from Bols) -- but they are not making an equivalent product.

-

I was going to mention this later on in the section about color, but one should keep in mind that the Bols liqueur products available in Europe and Japan are very good quality, whereas the Bols liqueur products available in America are crap. So, adding a teaspoon of Bols blue curacao to a 2-ounce cocktail for color isn't quite the same as dumping in a bunch of crap. Of course, cooks add all kinds of things to sauces to modify the color, including but not limited to prepared ketchup.

As for food coloring, Dave Arnold asked exactly that question during the color session Q&A: why not just use food coloring? Or, for that matter, why not add food coloring to a different clear liqueur to get the desired color? Uyeda said that wouldn't be challenging.

Japanese Cocktail Technique Seminar : May 3-4

in Spirits & Cocktails

Posted

I wouldn't say it is a direct word-for-word quote, no. Rather it's a tweet someone made from the seminar and attributed to Uyeda.

I discussed this very thing here upthread.