-

Posts

11,151 -

Joined

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Store

Help Articles

Posts posted by slkinsey

-

-

Hasn't that always been true?

-

Re gum Arabic and gomme syrup, buy the gum Arabic from these guys and make the syrup according to the instructions in this thread.

-

When the pressure outside the bag and inside the bag are equal - the bag wouldn't collapse ( just like when gravity and lift are equal an object would be in flight), when the pressure inside the bag is approaching zero - the bag inevitable collapses (it's not cooking - it's physics, really). Would you agree with me on that?

The bag only collapses because there is a temporary pressure disequilibrium. Once the bag collapses (which happens almost instantly), the inside and outside of the bag are in pressure equilibrium. This is only relevant with respect to a chamber sealer. For edge-sealer type machines, the inside and outside are always at pressure equilibrium.

Perhaps these graphics can explain.

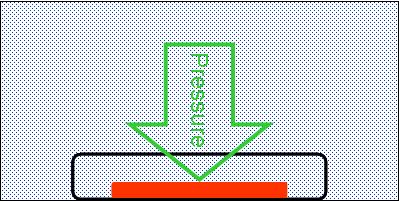

Here is a piece of meat inside of a bag. The bag is full of air. You can see by the air molecules that the inside and outside of the bag are at pressure equilibrium and the meat is under regular atmospheric pressure.

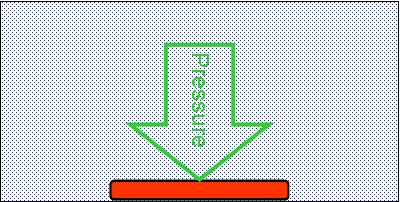

Now we have sucked most of the air out of the bag in a chamber vacuum and sealed the bag. The graphic below shows the conditions right after the chamber is opened. As you can see, the inside of the bag is at lower pressure than the outside of the bag (illustrated by showing that there are far fewer air molecules per square inch inside the bag compared to outside the bag). There is pressure disequilibrium, and the meat is not under regular atmospheric pressure (note that the pressure arrow is not touching the meat).

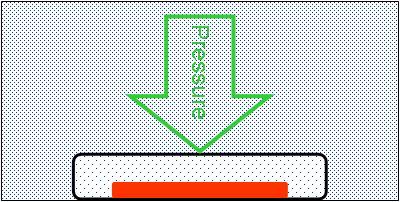

A split second later, the flexible bag material has responded to the pressure disequilibrium by bending under the atmospheric pressure. As a result, the bag is much smaller now, and close to the exterior of the meat. The external atmospheric pressure will continue to crush the bag material towards the meat until such time as the inside of the bag and the outside of the bag are at pressure equilibrium (illustrated by showing that the number of air molecules per square inch are the same inside and outside the bag). The meat inside the bag is now at regular atmospheric pressure.

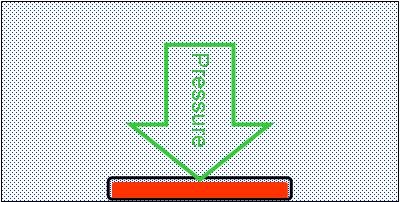

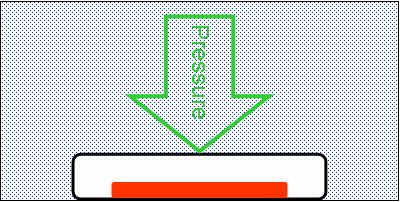

What if you remove 100% of the air from the bag? Well, much the same thing happens. You go from this situation when the chamber is opened:

To this situation a split second later:

The only difference is that there is a small amount of air remaining in the bag in the first example, and no air remaining in the bag in the second example. In both cases, the steak is under regular atmospheric pressure once the bag collapses.

The only way to have the steak under low pressure after the chamber is opened is to have the steak inside a rigid container. If the walls of the chamber cannot contract, then there can be no pressure equilibrium and the steak will remain under lower pressure. You end up with this situation:

-

1

1

-

-

Mike, I'm afraid you are incorrect about the items inside a vacuum sealed bag being below atmospheric presure.

Think about it: What is atmospheric pressure?

Atmospheric pressure can be simply described as approximately the hydrostatic pressure caused by the weight of the atmosphere. A more simple way of putting it is that atmospheric pressure is the combined weight of the air above us "pressing down."

If you reduce gravity, weight is reduced and atmospheric pressure goes down. When elevation increases the mass of air molecules above is reduced, and atmospheric pressure goes down. If climactic conditions create a "low pressure condition" the mass of air molecules above is reduced, and pressure goes down (the opposite is true for a "high pressure condition").

So, what happens with respect to pressure when we put a piece of beef in a bag and suck all the extra air out of the bag? Nothing, really. The mass of air molecules "pressing down" on the steak through the bag is exactly the same as the mass of air molecules "pressing down" on the steak before it was in the bag. In both conditions, the steak is under regular atmospheric pressure.

If we would like for the steak to be under reduced pressure, we must put the steak into a rigid container and evacuate the air from the rigid container. At this point, the mass of air molecules "pressing down" on the steak is very small, and the steak is under less-than-atmospheric pressure.

Another way to think about it is this: Suppose you took the steak in the vacuum-sealed bag and put it at the bottom of the ocean. Would the steak be at low pressure or high pressure? Now, suppose you took the steak in the vacuum-evacuated rigid container and put it at the bottom of the ocean. Would that steak be at low pressure or high pressure? (Answer: steak #1 = high pressure; steak #2 = low pressure.)

-

Oh, totally. Outside the context of a bar or restaurant, there are plenty of places a machine like this could potentially work. Although I think it will be substantially trickier than dispensing beer from a keg if the idea is to include fresh juices, etc. Japan, of course, is also a culture where people buy all sorts of foods from machines (e.g., french fries).

-

Yea, it could work as a novelty item in certain frat-boy-heavy contexts. Still, though, why go to all the trouble of coming up with a machine that mixes the drinks to order? Why not just have five internal tanks of premixed cocktails inside? Or, better yet, why not have a cart with iced premix in bottles wheeled around by a surgically enhanced blonde in a halter top? I guarantee she'll be able to generate more revenues for the business than any credit-card operated cocktail machine.

-

To be clear: You're not observing that the strip loins retain more moisture than the tenderloins, you are observing that the strip loins exhibit more moisture loss compared to the strip loins. How about this question: Perhaps the tenderloins had more moisture to begin with?

-

Proper dilution can be achieved by the addition of water. I assume chilling would be accomplished by running the liquids through some kind of heat exchanger.

Keeping it clean will certainly be a challenge. Residue is one of the things that makes the unfortunately ubiquitous "soda gun" so disgusting.

I don't disagree that theoretically a cocktail machine could be interesting. I do disagree, however, that it could be economical. It seems like you have two choices here:

(1) You have a place that doesn't have a particularly cocktailian clientele or staff. You don't want to spend very much money on the machine, which means that it's going to be fairly limited as to the number and kind of drinks it can make. The limited repertoire of drinks is okay, because you're not selling to cocktail sophisticated. The main questions would be: (i) whether your clientele is likely to want any of the more cocktailian offerings the machine makes; and (ii) whether it wouldn't be easier and more economical for the barman to make whatever drinks are ordered (especially in consideration of the fact that the drinks most likely to be ordered are either easily batched like an LIT or Cosmo, or simple highballs).

or

(2) You have a cocktailian place. In this scenario, you would potentially be interested in spending significant money on a machine with the flexibility to make a wide variety of drinks. The question of economics still comes into play, because in this case it is going to be more economical and still more flexible to simply hire and train staff.

Roger is clearly going after the first scenario, and success of his scheme would seem to depend entirely on the clientele of a non-cocktailian bar deciding that they want a Daiquiri or Gin Sour served out of a machine. The problem I have with his proposed model is that five bottles (let's say 4 spirits and 1 liqueur) plus two juices and two syrups #1 doesn't make for a very interesting or wide variety of cocktails, and #2 doesn't offer the ability to make any cocktails beyond those that are fairly easy for even a minimally talented bartender to make. If it's a beer-centric venue four deep at the bar, it's not clear that the ability to serve the occasional White Lady out of a machine is going to add to their bottom line. Certainly over here, their money would be better spend on a frozen drink machine.

-

The Japanese "hard shake" has been discussed here before. Whether this technique would be replicable by a machine is debatable. Indeed, whether any of the claimed benefits of the hard shake would stand up under rigorous examination is, in my opinion, highly debatable. What it does do, in my observation, is result in rounded-off "leftover" ice cubes in the shaker, and perhaps a larger volume of more uniformly small ice chips in the drink. Whether a profusion of ice chips in the drink is highly questionable, and if I've shaken a drink extra hard I like to double strain it so as to remove any ice chips from the final drink.

You want a colder cocktail? Start with colder ice, and use lots of it. Even starting with the same amount of identical ice, I find it highly unlikely that the hard shake produces a colder drink.

Getting back to Roger's cocktail machine... Roger, the first thing I would do if I were you is create a spec and cost for the machine, then do some market studies to determine if there would be any demand for such a machine. I very mucn doubt there would be, but you never know. Although MikeInSacto may be an exception, I believe that the vast majority of people who care about a well-crafted cocktail would not buy a cocktail that came out of a machine. Beyond that, if your "killer app" cocktail is the Long Island Iced Tea, it seems clear to me that you're not projecting this machine to be placed into venues with a cocktail enthusiast crowd. (Again, I'll point out that it is very simple to mix together one bottle each of the required spirits for a Long Island Iced Tea and then pour the pre-mix back into bottles, which will keep indefinitely for little cost. All that is then required to make the drink is filling a glass with ice, pouring in some of the pre-mix and topping with sour mix and a dash of cola. Most any bartender worth his salt could to it in 10 seconds.)

-

sygyzy, the reason you put the steak into the water bath at refrigerator temperature is because you want the steak to spend the minimum amount of time in the "danger zone" range of temperatures. What is the fastest way to warm up the steak? Put it in the water bath. It only makes sense to pre-warm-up the steak when you're using a cooking method in which the heat source is higher than the desired target temperature.

-

Why not extra heavy carbon steel?

-

The question is whether #2 would make them any moncy versus having a guy do it by hand. My guess is that it wouldn't.

-

There are two stages to preparing fresh fava beans.

Step one is taking the beans out of the pods. This requires no blanching.

Step two is removing the skin from the individual beans. This is most easily accomplished by blanching the beans in copious boiling water for several seconds, and then shocking in ice water. It is then easy to remove the skin by making a slit in the skin and squeezing out each individual bean. The goal is to cook the fava bean as little as possible, so that they retain their texture and best flavor.

Watch out for that glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency, though!

-

So, here are your questions:

(1) Do you suppose that people who might be likely to order those drinks would order them if made by a machine?

and

(2) Do you suppose that bars that might be interested in serving those drinks would be likely to purchase such a machine?

As for restaurants, I think that's a nonstarter. Either the bar volume at the restaurant is running at a sufficiently slow pace for the bartender to make these drinks entirely by hand or the bar is busy enough to be considered a "bar" rather than a restaurant for the purposes of this discussion.

-

So, Roger: Let's see a sample setup (what bottles, what juices) and a sample list of cocktails that the machine could produce.

-

I would suggest that the consumers of frozen Margaritas from the slurpee machine are not, on average, discerning consumers of classic cocktails. More to the point, a machine like this is a one-trick pony. Roger's machine seeks to be one that makes a number of different cocktails to order at the push of a button.

Some questions for Roger:

How many cocktails do you think your machine will make given 5 spirits, 2 juices and 1 bitters?

No liqueurs (e.g., Cointreau)?

What are some cocktails you expect this machine to make? Are we talking about a machine that can make you a Pegu Club or a machine that can make you a Gin and Orange?

What do you see are the advantages of using your machine over, say, batching 5 to 10 house cocktails under refrigeration?

-

For a fry pan, I'd say you want straight gauge and not disk bottom. You also want something with short flared sides. A lot of frypans I find have sides that are too tall and too steep, making them more like curved saute pans.

Sorry, I'm sure you've already mentioned the reasoning behind this, but why wouldn't you want a disk bottom fry pan? If you've got a nice saucier for wet/dry applications and are just using the fry pan for browning and whatnot I don't see what the problem would be with a disk.

Just like I said: "A lot of frypans I find have sides that are too tall and too steep, making them more like curved saute pans." As I point out in the article, you want short flared sides in a frypan, because this aids in the evaporation of steam and thus facilitates crisping of the food surfaces.

In addition, most disk-bottom designs do not have a base that extends all the way to the edge. Since frying involves letting foods sit still in the pan (as opposed to the constant movement of sauteing), you do not want a situation where part of the food item is over the disk and part of it is not. Since you would like to maximize your cooking surface in a frypan, straight gauge makes the most sense.

-

Frozen Margaritas are a drink that are specially amenable to being served from a machine. The "margarita machine" maintains a constant slurry of Margarita slush. That's a far cry from having a machine make a Martini or a Sidecar.

-

Roger, if you want to make a successful go of this, you need to consider your potential clientele, and more to the point you need to consider their clientele.

No one who is interested in a cocktail with bitters, or who cares about fresh juices, or who wants a classic cocktail is going to order a drink that's made by a machine.

-

I can't speak for Toby, but I think if you consider the stroke he's using there, you'll see that he's hardly applying any force to the muddler. If you're actually "pressing" the mint, you're applying more force -- and you're most definitely bruising more aggressively if you're pressing and turning. Also, the fist-sized bunch of fresh mint he's using means there is going to be a certain "cushioning" effect that will further lessen the force applied the herbage.

-

That is correct, it only has one handle. I haven't found it difficult to lift, but some people do. I have strong forearms. I find that the handle design also aids in lifting the pot -- you grip the handle close to the body of the pan and anchor the length of the handle along your arm.

-

The earliest recipes I've seen, in the Stork Club book and the Savoy Book, call for lemon juice and a little fizz water. No bitters. That said, I think that lime and mint often makes a more felicitous combination than lemon and mint.

I believe it's Dale DeGroff who says that the Southside came from the 21 Club in NYC. Laura Donnelly says in this NPR piece that the Southside comes from Chicago's South Side and dates to the Prohibition era -- but she seems a little too eager to accept the Chicago story as historical fact, and it seems improbable to me. Eric Felten also disagrees in the WSJ and suggests that it comes from the Southside Sportsmen's Club on Long Island (which would explain why this is an iconic East Coast country club cocktail and not an iconic Chicago cocktail today). The article points out that it is simply a Tom Collins with the addition of mint, which makes it unlikely it came from South Side gangsters in Chicago. Note also the spelling: "Southside" on Long Island, and "South Side" in Chicago.

-

George, I'm trying to pin down exactly what your conception of the cobbler is. It seems like you're using as your basis something like: base spirit, liqueur, sugar muddled with lemon twists and crushed ice.

This seems like it's going in a rather different direction from the cobblers with which I am familiar, and which seem to reflect the heyday of the cobbler, which were not made with distilled spirits at all but rather with a base of wine (either fortified or not) together with sugar, copious fruit (sometimes shaken together with the ingredients but always ornamenting the glass) and crushed ice. One sees the occasional recipe for a cobbler with spirits, starting with JT's whiskey cobbler. But this always struck me as a perfunctory add-on consisting of a simple repetition of the sherry cobbler recipe with a spirit base rather than the usual wine base (and resulting in a ridiculously large amount of spirits). More to the point, while one sees the occasional rare recipe for a spirit-based Cobbler, one never reads of anyone drinking one.

All of which is to say that I'd be interested to hear your basis for what you think constitutes a Cobbler. For me, the things that make a Cobbler a Cobbler are (1) the crushed ice; (2) a (fortified) wine base; and (3) lots of fresh fruit, some of it lightly muddled, but always plenty to ornament. I could see making an Icewine Cobbler or an Amaro Cobbler or a Vermouth Cobbler, but somehow a Whiskey Cobbler seems like a Julep without the mint. Is every crushed ice drink that includes neither bitters nor citrus juice a Cobbler?

-

Copper is much more expensive than aluminum.

Whether a 7 mm aluminum base is better than a 2.5 mm copper base for a sauté pan is a matter of opinion and preference, and depends on what you like to do with the pan. As I've said on any number of occasions, most American home cooks don't actually sauté.

Rob Roy

in Spirits & Cocktails

Posted

Your problem is that you're making the drink with single malt scotch. The Rob Roy (and, indeed, almost all cocktails) calls for blended scotch. Try The Famous Grouse.