-

Posts

2,383 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Store

Help Articles

Everything posted by Panaderia Canadiense

-

I'd start by trying a pan. The higher hydration in the loaf is going to naturally make it want to spread rather than stand, but the crumb looks so nice that I wouldn't want to diminish it by dropping the hydration level any. Oil will also relax your dough (it's the main reason why focaccia is normally a flatbread) so you can cut that back a bit, but I wouldn't go overboard. Otherwise, it's gorgeous and I'd definitely still eat it!

-

I'm a Red Oaktag and Crespa kind of gal myself. The Oaktag both for its striking shape and deep burgundy colour - it's a bit more bitter than most green lettuces but I'm the kind of person who will happily eat a plate of nothing but raw radicchio and endive provided there's a vinaigrette involved; the Crespa for its superior crunch, sweet flavour, and dressing-holding capacity. I'm also kind of sad about the disappearance of Iceberg up in North America. It's widely available and widely used here in Ecuador, as are gigantic heads of (far superior) Buttercrunch.

-

Those pots are of a type collectively called "paila" - they're actually small examples of the genre. The big one is brushed aluminum, and the smaller one is handmade beaten brass. Paila are the go-to pots for shallow-fat frying; larger cast-iron ones are where fritada is made, and the brass ones are the paila used for making traditional helado de paila - a fruit sherbet invented in Ecuador; this involves whirling large brass pailas full of fruit juice over ice.

-

For the curious, I spent my entire night rotating pans of hot cross buns through the oven. The final count was 174 buns (plus a few mutants), which baked in trays of 15. I also baked three cheesecakes in our most popular fruit flavours (raspberry, passionfruit-mango, and strawberry-blackberry) I don't have pictures of selling at the Cathedral, which runs five full-capacity masses on Easter Sunday - the volume of people who mob us with our little stand of carts is phenomenal, and it's not the kind of environment one takes a camera into. I came home with a few pieces of cheesecake but otherwise cleaned out, and with Easter greetings from everyone I know (about half of the congregation).

-

So, let's start with yesterday's lunch and dinner. Lunch was chicken salad sandwiches on injerto, with slices of a very mild queso fresco. Dinner, because I was too exhausted to consider any other options, was provided by my neighbour Belén. On Saturdays and Sundays in my barrio, I've got quite a staggering selection of street food available - there's community league football in our park, and number of enterprising neighbours bring out their portable kitchens to cook on the street. In general, there will be fried chicken, whole fried fish, fritada, llapingachos, and sometimes even empanadas de viento for dessert. Belén makes the best fried chicken and potatoes with coleslaw. For those interested in spicing, this is chicken dredged in flour seasoned with Maggi powder, Sabora Rojo, and black pepper before frying in a mixture of chicken fat and sunflower-seed oil.

-

Not quite beer nuts, rounder, crunchy sweet coating that's more like they've been battered than candied. Some Japanese sweet-coating peanuts are close. Manitoba Confitada (peanut crack) look like this: Hot Cross Buns! I'm happy to share a recipe, but let me cut one down from the 50-bun size I use…. And yes, it has been an exhausting week and blogging is much more work than I ever remember it being, but it's always worth the effort to share!

-

Well, I'll be in and out all day today and tomorrow. My mission today is to produce around 200 hot cross buns and some other tasty sundries for sale at the Cathedral tomorrow - I'm slowly introducing the tradition of Hot Cross Buns at Easter to Ecuador, with excellent reception here in Ambato. This morning after delivering the altar breads for tonight's midnight mass, Mom and I stopped in at El Fornace, a wood-fired pizzeria and coffee-house, for breakfast. We're being typical Ecuadorians this morning - coffee and cheese toasts! They were just banking up the fires in the oven, so no pizza for us. In the atrium, El Fornace does its best to fool you into thinking you're on a Piazza in Italy. While we waited for our coffees, there was complimentary hot buttered bread with ají. This is an excellent example of what I was talking about yesterday - Ambato-style ají sauce which is not very spicy but has a rich, creamy texture and a nice tang from tree tomatoes. Breakfast was triple-decker Andina cheese toasties. Latte and Mocha. El Fornace does quite good gourmet coffee. And once we got home, it was time to make 200 buns' worth of dough.

-

I was thinking of a sort of boiled shelled peanut that's kind of sweet (unlike ones from the Southern US which are salty but otherwise quite bland); I've only ever had the sweet kind at country fairs and music festivals in Manitoba - nowhere else in Canada. I quite like them. Hence my excitement. Manitoba-brand Maní Confitado must be exported to at least one English-speaking country as well as Central America and Mexico, just judging from the way they're labeled (Cacahuete is Nahuatl for peanuts and it's the word used north of Panamá, but in most of South America they're Maní instead….) I can hook you up with the company if you'd like - I suspect they're already getting as far north as New Jersey so Canada shouldn't present any special hurdles. They're labeled within an inch of their lives. EDIT - just checked the back of the package (and ate a few more) - they're a Colombian product; website at www.manitoba.com.co

-

Oh my goodness, I hit you with random snack food and didn't explain myself. Manitoba is a brand of traditional candied peanuts and I swear to you, they are so addictive that Mom now calls them "bag of peanut crack." They manage to be sweet, salty, crunchy, and chewy all at the same time, but never to excess in any one area - they're covered with a very light shell of panela and have a really intriguing molasses and salt flavour. We are hard-pressed to leave peanuts in the bag for next time. If I'm doing a marathon of intricate things, like these breads or larger fondant-decorated cakes, Manitoba are what keep me going.

-

Dinner last night fell into the category of "we are uninspired" - whenever this happens, it means that by default dinner will be roast chicken breast and potatoes with some sort of steamed veg on the side. No exception here. The evening's activities consisted of working for the Church: making three massive loaves for the Bishop's midnight mass on Saturday. These are quinua challah in three-and-a-bit pound loaves; they'll be consecrated and then shared with the congregation as part of the mass. I'm quite happy with how they came out this year, although I think the twist could have browned better on the side crust.

-

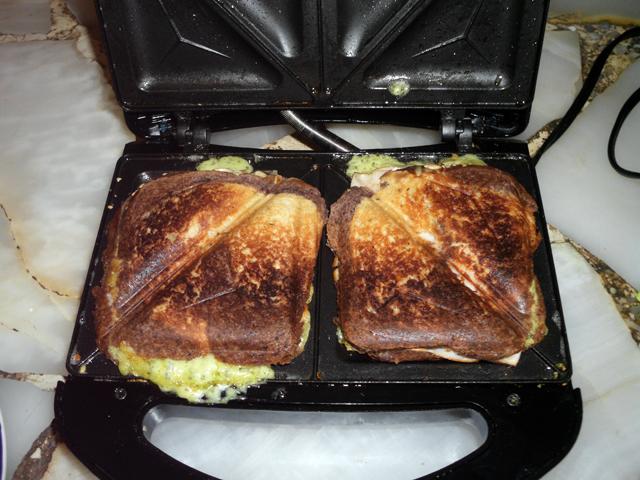

I just realized it's already almost dinnertime, and I haven't told you anything about what I've been doing all day…. I started off by eating a leftover cinnamon bun and drinking a mug of local cola - I was feeling sluggish and wanted a sugar and kola boost. Then I made granola bars. These ones have cranberries and raisins, by special request. The peanut paste is so thick that it has to be heated with oil and honey to get it to a malleable consistency (but this makes it much easier to melt the marshmallows, so it's not necessarily a bad thing….) I feel like I need to say a word or two about Ecuadorian peanut paste. This is not peanut butter in the sense that North Americans would recognize it - it's much stiffer and thicker, and generally just contains peanuts and a bit of oil. This is because Ecuadorians don't approach ground peanuts in the same way that North Americans do. It's an ingredient for thickening sauces, not a breakfast spread. If you want a breakfast spread you have to beat more oil into it. I'll have photos of the finished bar momentarily - my camera is recharging at the moment. Lunch was a bit more of a production number - jaffled turkey and cheese sandwiches on pan injerto. I don't know how I lived before I was given a Jaffle Iron.

-

I haven't actually touched on seasonings all that much, but Ecuador approaches this in a fairly interesting way. A well-stocked Ecuadorian spice cabinet will have the following in it: achiote, cumin, oregano, sazonador amarillo, sabora rojo, aliño, Maggi, curry, cinnamon, nutmeg, allspice, cloves, ishpingo, salt, and pepper. The combo of oregano-cumin-cinnamon is fairly common, and nutmeg is treated as though it's a spice for the salt kitchen and not the sweet one, but in general spices are used in small amounts and recipes are more geared towards showing off the natural flavours of the ingredients. Cilantro and lovage greens feature heavily in terms of fresh herbs, and most kitchens will also have a fresh ginger root for use in soups as well as the usual garlic, shallots, and onions. What you'll notice about that list is that it doesn't contain anything other than black pepper that adds "heat" to a dish. This is because unlike other Latin American cuisines, Ecuador's philosophy towards heat is that you add your own to the dish once it's at the table. Consequently, there might not be salt and pepper on the table (the food will invariably come impeccably seasoned) but there is always ají, a typical hot sauce that's normally made by each chef (not purchased - having store-bought ají on the table is seen as an admission that you can't cook). Ají sauces vary from province to province; the hottest ones come from the south, the most complex ones from the coast; Ambato ají often includes creamed chochos and tomate de árbol, which give it a distinctive tangy flavour. Saz Amarillo, Sabora, and Aliño also deserve special mention, because they are absolute staples necessary to achieving the subtle spicing that's typical of Ecuadorian recipes. These are spice blends; Sazonador is turmeric, celery, oregano, cumin, garlic, onion, salt, and bay laurel. Sabora is cumin, oregano, garlic, black pepper, salt, achiote, cloves, and cinnamon. Aliño is a paste made of garlic, red onion, white onion, oregano, cilantro, and celery or lovage. My bottle of aliño is empty, or I'd show you that as well. To answer your second question: farming here is a family affair - there are very few farms over 10 ha (25 acres), the majority of them are much smaller, and the grand majority, since they're often nearly vertical, are worked entirely by hand - tractors are only a common sight in the rice paddies on the coast; I've never seen a thresher or combine or a harvester, and I live in the heart of corn country. Most areas form cooperatives in order to get their produce to market. In the case of dairy, the pasteurizers tend to be collectively owned by the farmers. I have yet to see a corporate farm growing domestic produce here - even the large rice paddies are cooperative farms rather than corporate ones. On the domestic front, pricing is often set by the government in order to prevent speculation - staples like rice, milk, corn, oats, machica (roasted barley), and potatoes have fixed prices; since the farmers themselves are normally the ones bringing their goods to market, this goes straight to them. This explains the higher prices for staples at supermarkets, like the MegaMaxi vs. places like the Mercado Mayorista - the supermarket has to pay the set price, and then tack their profit on to that, while the Mayorista exists to connect buyers to growers directly. On the other hand, export crops, like bananas, broccoli, and pineapples, are grown on large corporate-owned plantations (Dole, Chiquita, Fyffes, and a number of other smaller players have huge extensions of land here, thousands of hectares.) In this case, about 25% of the banana plantations are fair-trade by world standards; the remainder are obliged by Ecuadorian law to pay living wages to their workers and to contribute to their social security - this is a huge step up from every other banana republic in the world. More and more small producers of the country's luxury crops: coffee, cacao, and exotic fruits, are forming fair-trade cooperatives and these co-ops are responsible for the collective bargaining process. Kallari, Caoni, and Pacari are Ecuador's international gold-medallist chocolate companies; all three of them are worker- and grower-owned fair-trade cooperatives with considerable bargaining clout on the world markets - taken together, they control more than 50% of the country's high-end cacao output. For the third question, I was tremendously lucky to find this house, which was built by an engineer who studied in New York, was heavily influenced by North American kitchen design, and who subsequently insisted on an open-plan kitchen with these gorgeous counters. The second stroke of luck comes in the fact that he and his family are tall people. I'm used to houses here having tiny kitchens with countertops that are probably perfect for normal 150 cm tall Ecuadorians - you may have heard me complain before about Smurf-Kitchen Syndrome. I'm 180 cm tall (six feet), and those standard low countertops cripple me. I also feel horribly claustrophobic in any room where I can place my palm flat on the ceiling without trouble. This house, over and above having such a well-designed kitchen, was built for people my size. It's a rarity and a luxury.

-

Is the English corruption of this where we get the term Lo Mein?

-

Latin American chochos (Lupinus mutabilis) are a slightly different creature from Lupini beans (L. albus) - I was reaching for a homologue for cooks outside of LatAm. Here, I can buy them already boiled and salted, which eliminates the need for me to worry about the toxic bitter alkaloid (chochos are classed as "sweet" lupines and contain far, far less of this alkaloid than Lupinis.) If I buy dried ones, a 15-minute spell in highly salted water in the pressure cooker followed by a thorough rinse in cold water, both rehydrates and de-bitters them, rendering them safe to eat in short order. Since the most commonly available form of chochos in Ecuador is fresh, boiled, and ready to eat, my recipe notation probably just says "peel them" because the skins add a mild bitterness to the broth that's undesirable. They're definitely a convenience snack here. If you're working with dried Lupinis, you'll need to do the pressure-cooking thing and also post-treatment soaking, or buy ready-to-use canned ones. Most "Latin American" specialty groceries in the US should actually carry chochos / tarwi as well - at which point, follow the recipe and just take off the outer membranes. Either that, or make a side-trip into the Trenton, NJ area and look for an Ecuadorian specialty shop (there are many in NJ, which has a large Ecuadorian expat community) - you should be able to buy bags of authentic ready-to-eat chochos from them.

-

What about using Ramen as a noodle-base for a dish outside of the context of soup? Because they make a lovely bed for dishes with thick sauces. Ginger chicken over ramen with veggies.

-

Last night's dinner was a family Easter tradition - holupche (cabbage rolls.) We had a nice little head of cabbage from the Mayorista on Sunday. But not so little, as it turns out, that it would fit in our small steamer. This meant hauling out the tamalero, a massive steaming pot, instead. We have no middle ground of steamers. Because we had ground chicken leftovers, we decided to do two different fillings - chicken and peas, and the more traditional beef and beet. Ready for the oven. The finished result (yum!). We grossly overestimated the number of leaves we had, so there was panfried holupche stuffing on the side.

-

I figured I'd consult an expert: I called Fidelina. If you're making Fanesca on the stove, you apparently need to stir it frequently to make sure the corn isn't sticking to the bottom of the pot, but not constantly - like any cream soup with inclusions. If you're making it over wood fire, you have to keep it moving. You might be able to do this in the Thermomix if you're willing to sacrifice the texture of the grains, which are normally left whole - but for making the squash and peanut cream base it would probably be a godsend. I have no idea about doing the final cooking in a pressure cooker, but I suspect it would work if your cooker is large enough to accommodate the volume of soup involved. Incidentally, I've had versions of this soup that aren't cream-based, that omit the peanuts, that substitute quinua for one of the grains, that omit the zambo, and that omit the bacalao entirely - and they're all called Fanesca. I think the intention is the most important thing. The recipe I've presented is an older, more traditional one with all the trimmings. I've been reviewing Fidelina's recipe because I was wondering the same thing - and when I called her, she reminded me that the instructions to not scrape down the pot are for making the soup in a giant cast-iron cauldron over a wood fire. She says on the stove you absolutely can and should scrape it, because it's going to behave quite differently. Fidelina also says the grains can be pressure-cooked before you take off their skins (and this is absolutely what I do - it saves hours of prep time), but mentions nothing about doing the final thing in the pressure cooker - she's always made too much volume to try this. And she says hello and happy Easter to all you people out around the world daring enough to want to make this dish! The fact that the tradition is being kept alive around the world thrills her to no end. I've only ever made Fanesca myself in big pots, often as part of a family celebration - my first time ever, because I proved so good at it, I was on chocho-shelling duty and then duly took a turn as a pot-stirrer. On the question of combining ingredients: Plantain-egg-and-cheese? That's a really common combo here - it's all that's necessary for a delicious breakfast! Slices of fried maduro with cheese on top and scrambled or hard-boiled eggs is called a Desayuno Guayaco (Guayaquil Breakfast). Peanuts-cream-squash is also the basis for a number of well-known dishes, including Encocado (peanut-coconut-curry) and Locro de Zapallo (a thick squash soup.) The concept of combining grains is present in the Volquetero (corn, fresh lupines, and plantain with red onion and tomato salad and tuna fish) and in most snacking mixes. HOWEVER, there are few non-ceremonial recipes that are so complex as Fanesca - Ecuadorian cooking in general is about highlighting the quality of one or two ingredients and allowing them to shine, and most recipes are far less involved. Fanesca, on paper, looks like it ought to be a sort of dog's breakfast of flavours and textures, but it somehow all comes together beautifully. The concept of a massive concatenation of ingredients shows up again around Día de los Difuntos with the traditional Colada Morada. Apart from that, I can't immediately call to mind any other recipes that almost require communal participation.

-

Alright! Holupche are in the oven, I've got a few minutes. Let's talk Fanesca! This is a dish unique to Ecuador and unique again for only being prepared during Holy Week. It's a traditional hearty soup that has been around since before Christianity came to the green shores of South America - it used to be linked to the festival celebrating the first flowers of the season, Pawkar Raymi, in the Incan calendar. This was supplanted by Catholic mythology of Easter, which coincides on the calendar, but the soup is so tasty that it was preserved (I like to think that nobody wanted to give it up!) There are 13 ingredients that are absolutely essential to Fanesca, all of which come into season around now; they traditionally correspond to either the 13 lunar months in a year, or to the 12 apostles (rice, peanuts, leeks, pumpkin, zambo, chochos, peas, cabbage, habas, white corn, white and red beans) and Jesus (bacalao). It's a milk and cream-based soup. In the mercados, sellers have made preparation much easier - the grains are shelled, and the squashes can be bought already cut up into convenient chunks. The bright red tubers next to the bag of pre-chopped zambo are mellocos, which make their way into the Ambateño variants on the recipe. There's a big difference between the flesh of a zambo and that of a squash. Preparation is usually a family or community event that spans two days of effort, because there are a number of legumes and grains that require special handling so as not to make the soup bitter - particularly, the habas (a type of broad-bean), chochos (lupines), and peas, whose outer casings are all removed by hand before the pulses are added back to the final soup. Recipes are normally for huge amounts of Fanesca, and that's because the whole community has chipped in on the ingredients and come together for the preparation. Community-made Fanesca comes out of huge cast iron cauldrons that bubble over wood fires. Sadly, this part of the tradition is diminishing, and it's only possible to sample soup made this way in the more remote Quichua communities where Pawkar Raymi is still celebrated - it used to happen in the cities as well. There are three traditional accompaniments, which are floated on top of the Fanesca when it's served: a slice of soft, sweet white cheese, a hard-boiled egg, and a fried ripe plantain. A further dozen or so ornaments may be added at the chef's discretion; these include bacalao fritters, patacones, small empanadas stuffed with bacalao and potato, caramelized onions, celery or lovage leaves, chopped green onion, cilantro, and ripe red ají or luqutu peppers. A version of my abuelita Fidelina's recipe can be found in the Salt Cod Diary, if you want to cook along. I've substituted Acorn squash for Zambo in this version, which will make life easier for cooks in parts of the world where Zambo is not available. If you want your Fanesca less thick, substitute either Zucchini or Spaghetti squash for the Acorn squash. If you don't like rice in your soups, you can substitute green or brown lentils - this is done at the chef's discretion. And if you want to be an Ambateña, you can substitute the smallest Melloco you can find for the cabbage. This recipe has been cut down from one that serves 200 - an entire barrio, which is how Fidelina, who is now 96 years old, learned to cook it.

-

I didn't either; it might be a Latin American thing - in previous years, I've already had the rabbit or lamb in the fridge for Easter dinner; this is the first time I've ever tried to visit a butcher during Holy Week! I have the freezers that are part of my fridges (and those have turkey and chicken and fish and beef in them), but I don't have a standalone - it's on the wish list. Knowing now that meat takes a vacation, I won't be caught short again. When I found out about it, my first thought was "why, oh why, don't other countries do this!?!?!?" It's so convenient, really ecologically sound, and if you provide your own tiffins there's no extra charge at the restaurant for doing it. The only other place I know of that does tiffin service like this is India, and even there it's quite different, with the restaurants providing the tiffins. I own a 4-tier stack, because I like my salad to come separate from the meat/rice/gravy part of the meal. There is so much Maggi-love in Ecuador! Maggi is one of the most common and popular spices here, but it's not just the bottles of strong dark sauce - it's also a brand of bouillon powder, a seasoning paste, and instant soups. Use depends on presentation: the sauce is used with fried foods (usually during preparation), the bouillon to quick-start soups and as a component of breading for fried things, the paste as an adobo for meats that would be tough if they weren't pre-seasoned, and the instant soups as a fast convenience. Oddly enough, a bottle of Maggi bought in Ecuador will have a slightly different flavour from one in Peru or Colombia - the recipe seems to change slightly depending on country. I have never seen the seasoning paste anywhere but in Ecuador. The one thing that all Maggi products in Latin America share is the presence of Lovage in the mix, which is actually called "Hierba Maggi" in Ecuador - it's usually there in place of MSG. Non-Maggi branded products even use this name for the herb when it's present - I've got a finishing salt that's about half herbs, that lists Hierba Maggi as an ingredient. I would assume after they've formally broken Lent, which would be after the high mass commemorating the last supper on Holy Saturday? In practice, Easter Sunday dinner is Fanesca and grilled sausages, so I'd assume that at least the charcuterers are open on Saturday afternoon. Either that, or the faithful have go to the MegaMaxi and buy something in a blister pack from their meat coolers. MegaMaxi doesn't recognize Lent at all, although it does put out the Fanesca grains and boxed bacalao when Holy Week approaches.

-

Before I make it home, though, there's one more stop: the Fruteria at the top of the hill. This is a shop that's larger than a Tienda but smaller than a Supermarket, and that has a full greengrocer's as well as dry goods and dairy. In typical Ecuadorian fashion, it's a bit of a jumble - if you can't find what you're looking for, you joke with the proprietor about it, and they'll point it out. Case in point: quail eggs are housed with gummies and gelatine shots. Along with the lettuce and some other sundries, I got a Sunny Peach Nectar and a gelatine shot. Both are very refreshing. While I drank that, I took in the beautiful view from the park in front of the fruteria. And on my way home, I passed by one of my neighbours, a basket-weaver, to see how her ducklings were coming along - they're getting so big! Of course, if you can't find what you want in the mercado or at the fruteria, you can always wait for the fruit truck to come along….

-

Next up: PanCan remembers that she lives in a very observant, deeply Catholic country and she's blogging during Holy Week. I went to the Mercado Central in search of some ground lamb, thinking that it would make a nice stuffing for the Holupche I'm making for dinner. But first, a quick stop at the Ambamiel kiosk - this is the outlet for the county's cooperatives of beekeepers. They sell all things bee-related, up to and including hives (obviously not on-site, but they'll hook you up with local apiculturists if you want to buy or rent bees.) I wanted some bitter honey, a product gathered by keepers of the large native ground-bees, which is a great remedy for sore throats. The Mercado Central is the city's oldest market, in the heart of downtown. It's recently had a facelift and internal renovations. Walking up to it, you get a real sense of what Ambato is like - even the sidewalks are crammed with sellers, and you can see that while the market may have been improved and remodelled, the surrounding buildings haven't - they're the few Art-Deco survivors of the 1949 quake that levelled the city. Ambato is a study in this kind of contrast, the past being kept standing by the present. Inside, my disappointment is palpable. Meat is completely prohibited to the faithful during Holy Week; all but one of the butchers has been on vacation since Monday! The sole remaining seller has only a few small cuts of goat, which are not what I'm looking for at all. You can see that El Ovino, which specializes in young goats and sheep of all ages, is literally the only one with the lights still on - everyone else is long since packed up and gone. Sigh. Maybe the butchers in the Mercado Modelo will still be there? It's just a couple of blocks away, so why not? In order to get a good shot of this market, I had to cross the street. This meant I ran up against the temptation of Subal, one of the city's most popular bakeries. Oh no, look at that pastry case. They have donuts! Now I want a donut. (I'm definitely with Oscar Wilde on this: one should always yield to temptation.) These are old-fashioned style chocolate glazed donuts. They're also about the only donuts in the city. LIght diversion accomplished, it's time to take a look inside the Modelo and see if the butchers here have packed it in for the week as well. Yes, yes they have. The only ones left in the meats section are a pair of hardy fishmongers doing brisk trade in fresh and salted fish. The Modelo has juice bars on the main floor! Laughing at myself, I head homewards. But hey! It wasn't a total loss - one of the fifty-cent stores had a spring whisk, something I've been looking for for quite some time…. And at least there were donuts!

-

To start with, Mom and I decided on Brisa y Mar (the same restaurant I showed you in the Mercado Central food court, but their actual sit-down location.) She's not a big fan of Fanesca, but she does like Ecuador's take on seafood, so this seemed to be a solution that would make us both happy. For those of you thinking of a visit to Ambato, Brisa y Mar is in a converted house on the corner of Los Shyris and El Inca. As in most Marisquerías (seafood houses), you get a bowl of mixed canguil and chulpi with the menu when you sit down. Mom decided, after much deliberation, on an Arroz Lleno de Mariscos (rice filled with seafood) which includes a bit of everything. In this case, it had small freshwater mussels and saltwater clams, squid, octopus, scallops, shrimp, and chunks of corvina (sea bass). The sauce is a mildly spiced mayonnaise. A bowl of limes and a lime-press arrives at the same time as your main course - this is so that you can control how much citrus you want on your dish (if any). My Fanesca came looking picture-perfect. I'll talk in a bit about how this is prepared, but for the moment you should know that what's floating in it are the traditional accompaniments: a fried plátano maduro, a hard-boiled egg, and a chunk of sweet Queso Manabita (a style of fresh cheese made with Brahma milk, common to the province of Manabí). I had been hoping for a bacalao fritter, but that's something that is at the election of the chef…. ….Because some chefs prefer instead to add chunks of the bacalao directly to the soup. This is the case at Brisa y Mar. About halfway through the meal, we realized we also wanted patacones (fried smashed green plantains). They're a sort of crispy-soft accompaniment to the heartiness of the soup, and they're also thoroughly yummy dipped in the mayo. At this point I'd been stealing mussels off of Mom's plate for a while. She retaliated by dipping her patacones in my soup. Brisa y Mar also offers Tiffin Service - the most common type of take-out in Ecuador. You bring in your lunchbox (or send it with a runner), and they fill it up for you. Most tiffins are stainless steel in two or three layers, with or without a thermal bucket (like the one shown here). This is to make it easy to reheat your lunch at the office - most lunchrooms have a small induction plate you can put your bowl on to quickly heat up your soup and main course.