12. 米粉 (mǐ fěn)

I’ve said this before, but it seems like every town and city in Guangxi has its own noodle speciality. Eaten for breakfast, lunch, dinner, midnight snack or whatever, these are almost always rice noodles (米粉 (mǐ fěn)) here in the south. 面条 (miàn tiáo) wheat noodles are more common in northern China.

Note: mǐ fěn is pronounced like 'mee fun'.

Although rice noodles can be fried (炒粉 - chǎo fěn), the most popular dishes are all soupy noodles. It would be impossible to list every rice noodle dish, but here are the three most common and famous.

老友粉 (lǎo yǒu fěn) – Nanning Old Friend Noodles

As with many Chinese dishes there is a story behind the name. This differs slightly from telling to telling, but the basics remain the same. It is said that, 100 years ago, there was an old man who was suffering from some ailment (often said to be a bad cold) and was basically withering away as he had no appetite for life, never mind food. All attempts to reach out to him were rebuffed until his oldest friend made him a bowl of noodles using what he happened to have to hand. As soon as the invalid smelled the dish he perked up and asked to try it. He loved the dish and was soon restored to full health. The story and the noodles fame spread and small shacks all over the city started to sell this new dish known as – old friend noodles!

Apocryphal as the story probably is (I almost hope it’s true), the noodles remain very popular in Nanning, Guangxi’s capital city where they are available on every corner. Here is one example I ate in a small hole-in-the-wall place near Nanning railway station on my way home from Vietnam in 2018. As with all these places, the diner is free to add whatever condiments they prefer. Depending on the restaurant, you may also be asked what type of noodles you want – round or flat.

The rice noodles are served in a broth with pickled bamboo shoots and fried chilli peppers. Additionally, it includes garlic, scallions, fermented black beans and pork or pig offal. For me, what sets it apart is that it also contains tomato, somewhat unusual in a noodle dish. The overall flavour combines a certain tartness from the bamboo with a mild spiciness. And it is something that cuts through the worst cold symptoms.

螺蛳粉 (luó sī fěn) – Liuzhou River Snail Noodles

There is archaeological evidence to suggest that the local people in Liuzhou were eating snails thousands of years ago. It took until the late 1960s or early 1970s for someone to put them together with the local rice noodles. Precisely who that was is a matter of great argument in the city.

Whoever it was, is kind of irrelevant now. The city is awash with places making and selling the dish. In fact, many visitors say the city stinks of luosifen. It is a divisive smell. I liken it to the asparagus pee phenomenon – some people smell it and hate it and some just don’t smell it at all. I just don’t. Either asparagus or luosifen.

螺蛳 (luó sī) - Liuzhou River Snails

I’ve written about this dish before, particularly here, so I won’t repeat myself too much other than to say the dish consists of rice noodles served in a very spicy stock made from the local river snails (a type of small Viviparaidae which live in the local river, the Liujiang, as well as in local rice paddies, ponds etc) and pig bones which are stewed for up to 16 hours with black cardamom, fennel seed, dried tangerine peel, cassia bark, cloves, pepper, bay leaf, licorice root, sand ginger, and star anise. Various pickled vegetables, dried tofu skin (you may know this by its Japanese name, ユバ - yuba), fresh green vegetables, peanuts and loads of chilli are then usually added.

Liuzhou Luosifen

Two years before the pandemic, local manufacturers started making ‘instant luosifen’ to be sold in packets (for considerably more than the real thing). None of them are a patch on the dish made in any small Liuzhou restaurant, but appeal to those who cannot otherwise get their kick away from Liuzhou. The noodles became the No 1 seller during the pandemic and the various lockdowns. Ironically, Liuzhou was never locked down.

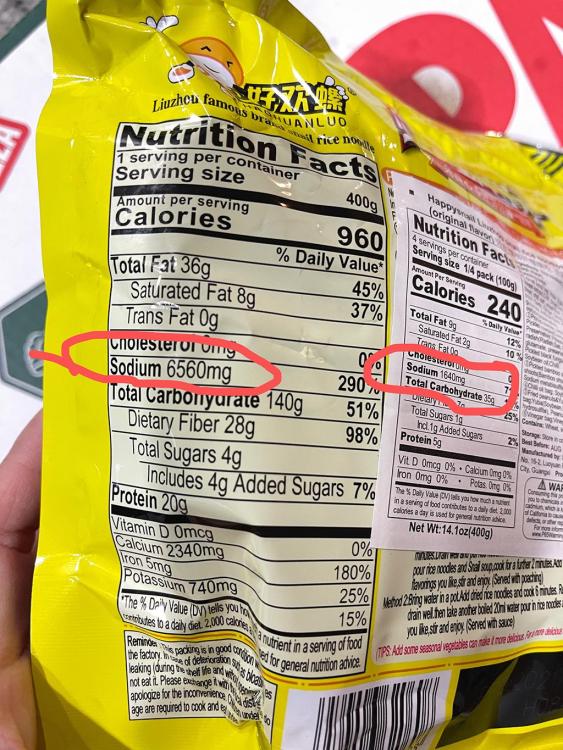

However, a Guangxi friend, a nurse, who now lives in Tennessee, has pointed out to me that the bagged luosifen contains ridiculously high levels of sodium. One bag contains 6,560 mg of sodium. The maximum suggested by the American Heart Association is 2,300 mg and they would like to reduce that even further. The US sellers have relabelled the bags suggesting that a serving only contains 1,640 mg*, but that is based on a serving being a quarter of a bag. The whole bag is clearly labelled as being one serving and who is this cretin who buys a bag of instant noodles and only serves a quarter of it? My friend has given up eating luosifen until she returns to Guangxi for a visit. Save up your cents and come to Liuzhou. Heck, I’ll even buy you a bowl as a welcome!

*Still above the AHA’s target of 1,500 mg.

桂林米粉 (guì lín mǐ fěn) - Guilin Mifen

The rather prosaically named Guilin Mifen (literally Guilin Rice Noodles) is the tourist city’s most popular. It is said by some to be around 2,000 years old. Again it is rice noodles in a broth with pork (or beef), fried peanuts, pickled cow peas, bamboo shoots and dried turnips. Chilli powder, green onion, coriander leaf/ cilantro etc are provided for you to add to your own preference. There are Guilin Mifen restaurants all over the city, determined to separate you from your cash.

Guilin Mifen

Guilin Mifen (Closeup)

Guilin Mifen Condiments and Additions. Note: A similar selection is provided for all the dishes here.

.thumb.jpg.cab0f0e593ea63743c3868fae1f0bd75.jpg)

.thumb.jpg.ae6e3070d7d3909da75cc5982f149f65.jpg)