5. Sossidges

In the 1970s (and later) in Britain, one of the most popular television shows, broadcast on a weekend evening, was “That’s Life” hosted by one Esther Rantzen. It started out as a consumer protection show, challenging semi-legal or dishonest practices in stores etc., but soon changed into a general light entertainment show – and when I say “light”, I mean feather-light.

The episode most people remember featured a talking dog named Prince, which was claimed to be able to say “sausages”! This went viral as we never said then, and to this day, British people of a certain age often pronounce “sausages” as the dog supposedly did. The fact that the dog’s owner was manipulating the mutt’s mouth and throat and very obviously using ventriloquism didn’t bother anyone!

Prince was able to “say” a few other words, but, significantly, it was sausages that struck a chord with the British people, so important are they in British cuisine (as they are in many others).

So, it is no surprise that the asinine YouTubers have to include sausages in their must-see list of what to eat in the UK. That sausages are included in the full breakfasts discussed above isn’t enough for them, because in their deluded minds sausages are what the British live on! We eat little else!

There is no denying that we eat a lot of sausages, but what these people want to eat is that classic “Bangers and Mash”. So, off they all go like 19th century explorers to discover exactly the same places that every other of the breed has already found. What they don’t realise as they rhapsodise over their lunch is that most of them aren’t eating “bangers and mash”, at all!

I lived in Moscow in the latter days of the Soviet Union, when food was very scarce and what was available was very poor quality. Cabbage and gristle stew was the mainstay, unless you were a top ranking communist or a pampered foreigner. I’ve mentioned this in detail here.

Several years later, long after the USSR collapsed and food supplies were again available normally, a fashion arose among a certain segment of the Muscovite population. Restaurants opened specialising in cabbage and gristle and became briefly popular!

This reminds me of the YouTubers seeking out war-time food which most people hated at the time. “Bangers” were made out of the sweepings of the abattoir floors mixed with cereal and water, causing them to explode when cooked, hence the name. Cheap and nasty.

Apart from the fact that they would probably be illegal now, standards have risen and, although the British still love a sausage, they want something non-explosive. Supermarkets now all sell what they call “premium sausages”, or something similar, while their regular sausages are what the WWII housewife could only dream of..

And although there are many cafés and pubs offering “bangers and mash” on their menus, the sausages are a lot better than war-time bangers. In fact, it is actually more common now to see the dish described as “sausages and mash”. Any café selling real “bangers” wouldn’t last the week.

So, what is the dish “bangers and mash? Simply, fried sausages served with mashed potato and an onion gravy. This is a simple, filling dish which is easy for the café or pub to prepare in large quantities. The sausages today will range from decently well made and seasoned to specialist artisan sausages.

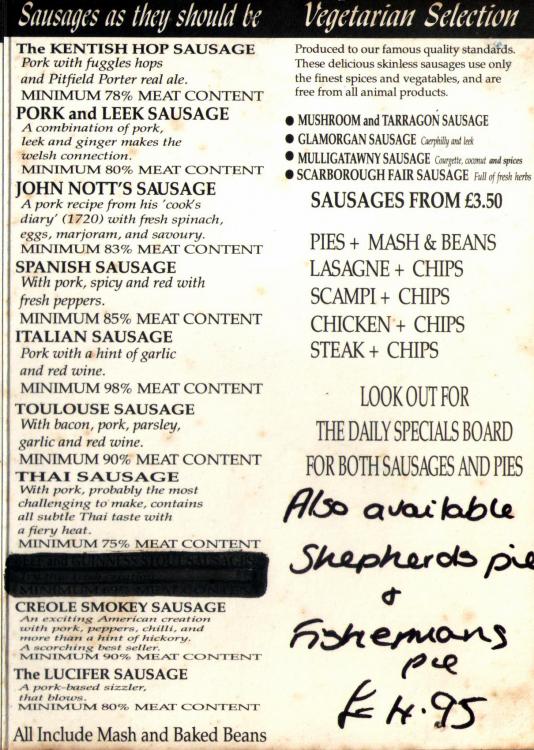

And not all sausages are served with mash. 25 years ago, I regularly ate lunch in this pub near London University, where I worked.

In fact, I ate there the day before I left for China. Here is the menu from that day - it changed regularly.

Also, in 2019, I ate this traditional London sausage from a street food stall. Delicious.

For those wishing to taste real, traditional, regional sausages (and some newbies) made by real human beings here is a round up up some of the best types.

Cumberland

Probably the best known traditional sausage is the Cumberland sausage. This has been around for about 500 years and is noted for its special shape. Rather than being formed into links, it is usually one long sausage, coiled into a spiral. In 2011, the “Traditional Cumberland Sausage”, to give it its official name was awarded Protected Geographical Indication (PGI) status, meaning its specifications and area of production are legally protected..

Cumberland sausage consists of coarsely minced pork, seasoned with black pepper, nutmeg, cayenne, thyme and sage (we don’t use herbs and spices?). The meat content is a minimum 85%, often higher. But the word to look for is that “Traditional”. Some supermarkets do sell mass-produced Cumberland sausage without that word and meat content can fall as low as 45%. Without “Traditional”, there is no protection.

Image by Andy / Andrew Fogg; licenced under CC BY 2.0

Lincolnshire

Lincoln sausages are also made with coarsely chopped pork and breadcrumbs / rusk, but this time flavoured with sage, pepper and onion. Minimum meat content is 70% and natural casings are used. Sulphite is is usually added as a preservative (450 ppm maximum).

Image by Chris Mear; licenced under CC BY 2.0

Oxford

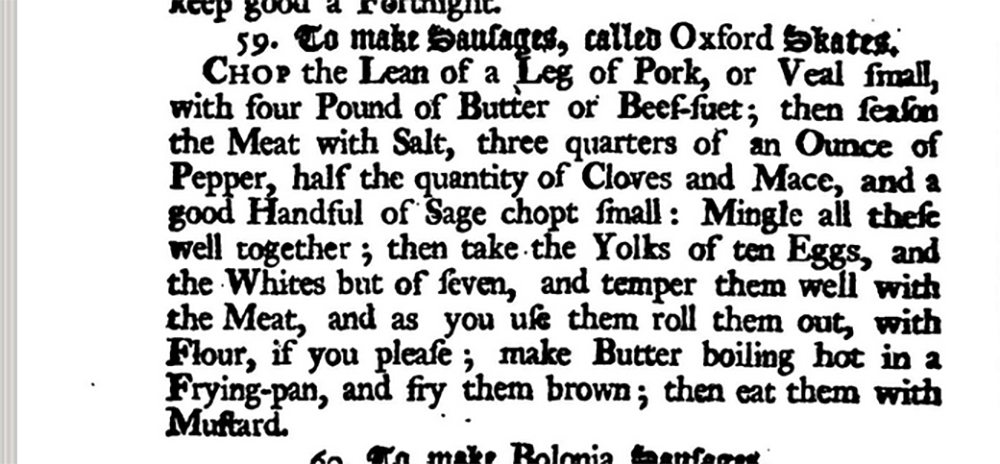

Oxford sausages date back to the 18th century. The John Nott’s sausages in the menu I show above are a type of Oxford sausage made from a recipe on page 488 of his book, “The Cook's and Confectioner's Dictionary: Or, the Accomplish'd Housewife's Companion” (link to digitised edition), published in 1723 (not 1720 as the menu claims). However, they were truly popularised by being included in Mrs Beeton’s “Book of Household Management” (link to downloadable version, recipe on page 837) published in 1861.

John Nott's recipe for Oxford Sausages

Quote837. INGREDIENTS.--1 lb. of pork, fat and lean, without skin or gristle; 1 lb. of lean veal, 1 lb. of beef suet, 1/2 lb. of bread crumbs, the rind of 1/2 lemon, 1 small nutmeg, 6 sage-leaves, 1 teaspoonful of pepper, 2 teaspoonfuls of salt, 1/2 teaspoonful of savory, 1/2 teaspoonful of marjoram. _Mode_.--Chop the pork, veal, and suet finely together, add the bread crumbs, lemon-peel (which should be well minced), and a small nutmeg grated. Wash and chop the sage-leaves very finely; add these with the remaining ingredients to the sausage-meat, and when thoroughly mixed, either put the meat into skins, or, when wanted for table, form it into little cakes, which should be floured and fried. _Average cost_, for this quantity, 2s. 6d. _Sufficient_ for about 30 moderate-sized sausages. _Seasonable_ from October to March. Isobel Beeton's Book of Household Management

Unusually, the Oxford sausages are traditionally made from a 50:50 mixture of pork and veal and are highly spiced with pepper, cloves, mace, sage, and nutmeg and flavoured with lemon and herbs. In recent years, their has been a movement against veal by the animal rights mob, so some makers, though thankfully not all, are substituting lamb or going for 100% pork.

Image by Kaihsu Tai; licenced under CC BY-SA 3.0

Newmarket

Newmarket pork sausages are, surprisingly, from the horse-racing town of Newmarket in Suffolk, England. Their are two varieties, each made by a different Newmarket family. In 2012, the two were awarded joint PGI protection.

Image by Allexbrn; licenced under CC BY-SA 3.0

Manchester

Manchester sausages are made from pork, traditionally flavoured with white pepper, mace, cloves, ginger, sage, basil and nutmeg.

Marylebone

The Marylebone sausage is named for Marylebone, an area in north-central London. They are seasoned with mace, ginger and sage.

Gloucester

Traditionally, Gloucester sausages are made using pork from the rare-breed pig, Gloucester Old Spot and are flavoured with sage. In 2010, the Gloucestershire Old Spots Pig Breeders' Club was awarded Traditional Speciality Guaranteed status by the EU, meaning that pork labelled as Old Spot, must be the real deal.

Lorne Sausage

This might be stretching the definition of sausage a step too far for some, but in Scotland, we are proud of our beloved Lorne sausage (even if we rarely call it that). It is made with beef and spiced with black pepper, nutmeg and coriander seed. Unlike most sausages it is not cased in intestines, natural or synthetic, but pressed into a square shape and chilled. It is then cut into square slices. So, in most of Scotland, it is referred to as “square sausage”.

Square sausage is usually used as part of a full-Scottish breakfast, but also (my favourite) often served sliced in a bread roll with ketchup or brown sauce. Its shape and size make it a perfect fit.

There is a fascinating article here giving the history of the Lorne sausage and the origin of its name (plus a recipe).

Public domain image

Black Pudding

Many countries have their versions of blood sausage and black pudding is the British one. Well, actually at least two. Scottish and English are slightly different.

The name “black pudding” causes some confusion. It shouldn’t. The original meaning of “pudding” was

Quote1.I.1 a. I.1.a The stomach or one of the entrails of a pig, sheep, or other animal, stuffed with a mixture of minced meat, suet, oatmeal, seasoning, etc., boiled and kept till needed; a kind of sausage

c 1305 Land Cokayne 59 Þe pinnes beþ fat podinges Rich met to princez and kinges.

OED

Today, the word retains its original meaning mainly in Scotland and Northern England.

Black pudding meaning a “kind of sausage made of blood and suet, sometimes with the addition of flour or meal” appeared in the early 16th century.

Both are made with pig’s blood and oatmeal, but the English variety contains large lumps of fat. It is also spiced. Scottish black pudding does contain fat, but it is finely ground and seldom visible. English black pudding is spiced (see recipe below), whereas Scottish is not, leaving the natural flavours to dominate.

Opinion varies as to which is the better, with participants in the discussion split mostly by region of birth. I prefer the Scottish version, not for any puerile nationalism or prejudice, but because it is clearly better!

Stornoway black pudding, from the capital of the Outer Hebrides island of Lewis and Harris in Scotland’s far-west, has PGI status and is widely considered the best of the Scottish type.

Image by me.

There are many other British sausages. Pork and apple is a favourite and I regularly ate venison sausages from this man's farm shop. Most European sausages are also easily available in supermarkets. The best place for British sausages, however, remains good old traditional butchers'shops. Sadly, a dying breed.

If you roll into a British café today, unless you are very unlucky, you are not going to be met by a plate of congealing fat and detonating pink slime. You are more likely to find something like this. Enjoy!