Search the Community

Showing results for 'brooklyn copper cookware'.

-

Welcome to eGullet, Toronto. And thanks for your review. Few people here have spent much--if any--time cooking in thick, tin-lined bottoms, so you must excuse them for slamming this construction as antiquated. I believe Mac Kohler's Brooklyn Copper Cookware will succeed in much the same way that my friend Bob Kramer's knives have. Please post again when you've used these fabulous wares--with photos.

-

Copper vs Stainless Steel Clad Cookware: Is it worth the $$$?

Toronto416 replied to a topic in Kitchen Consumer

The demise of tin-lined heavy copper cookware is as overblown as the demise of sailing, riding horses, film cameras, beeswax candles, and wearing stockings with garters. E.Dehillerin sells a large array of tin lined copper cookware - all new current production pieces by Mauviel that are constantly being replenished: http://eshop.e-dehillerin.fr/en/copper-copper-lined-with-tin-xsl-243_271.html If you go to Mauviel's French language site, you will see the tin-lined M'tradition line of heavy tin-lined cookware - just click 'Francais' and then 'les collections': http://www.mauviel.com If you click the English language option you are redirected to the American distributor's site, and alas no tin-lined copper. I ordered a new current-production 11" heavy copper tin-lined Mauviel rondeau from France in November 2015. It is 3.3-3.5mm thick, and marvellous for browning and then braising meat. The tin is quite non-stick, the pan suffers no hot-spots, and the thick copper conducts heat such that the contents are enveloped with heat, permitting wonderful stove-top braises. It of course also performs very well in the oven, but so do vessels that would not be suitable for stove-top braising. Cooks far more experienced than me have touted the advantages of heavy tin-lined copper cookware (see boilsover above, and the many photographic examples he provided of copper pots being very much in evidence in professional kitchens). As mentioned above, Julia Child was a big fan of tin-lined heavy copper cookware (just don't follow her cleaning instructions). When she was developing and testing the recipes in her 1961 classic Mastering the Art of French Cooking, she did most of that using tin-lined heavy copper cookware she had bought from E.Dehillerin. If tin-lined heavy copper cookware was good enough for developing one of the greatest and most enduring cookbooks of all time, then that's good enough for us mere mortals. Julia Child would have been excited to see the quality of cookware now being made in the USA by companies such as Brooklyn Copper Cookware. I just wanted to bring attention to this old-world artisanal approach to making copper cookware for those who value slowing down to make good food, drink good wine, and enjoy good company while respecting tradition and indulging in the finer things in life. -

Copper vs Stainless Steel Clad Cookware: Is it worth the $$$?

boilsover replied to a topic in Kitchen Consumer

You're funny. Here's a list of institutions and restaurants (you count their and chefs' stars) for which I can instantly find photos of chefs using copper: Palias De L'Elysee (Ch. Joel Normand) Senat (Ch Jean-Jacques Mathou) Assemblee Nationale (Ch. Christian Peccoud) Hotel de Matignon (Ch. Yves Delplace) Arpege (Ch. Alain Passard) Cazaudehore et la Forestiere (Ch. Gaston Haussais) La Closerie Des Lilas (Ch. Fabrice Vulin) Dalloyau (Ch. Pascal Niau) Fouquet's (Bernard Leprince) L'Intercontinental (Patrick Juhel) Le Grand Vefour (Guy Martin) Jacques Cagna (himself) Ledoyen (Ghislane Arabien) Lenotre (Gaston himself) Brasserie Lipp (Jean-Paul Juliard) Lucas Carton (Frederic Robert) Maxim's (Michel Kerever) Potel et Chabot (Jean-Pierre Bifi) Hotel Ritz (Guy Legay) Ritz Club (Domenique Fonseca) Bernard Dufoux (himself) La Cote Saint-Jacques (Michel Lorain) Les Crayers (Gerard Boyer) Au Crocodile (Emile Jung) L'Esperance (Marc Menau) Hotel Martinez (Christian Willer) Residence de la Pinede (Herve Quesnel) Paul Bocuse (himself) Les Pres D'Eugenie (Michel Guerard) Aubere Des Templiers (Francois Randolphe) Troisgros (Pierre and Michel) Georges Blanc (himself) Chez le Baron de Rothschild (Nadine, Robert Palluau) Seems they all are conspirators in this. You might also be surprised how many fans Brooklyn Copper Cookware has among the illuminati right there in New York City. I'll leave it to them to name names in their promotional materials. -

Copper vs Stainless Steel Clad Cookware: Is it worth the $$$?

boilsover replied to a topic in Kitchen Consumer

Well, there's Craft. And Per Se. And Chef's Table at Brooklyn Fare. . According to Craft's Chef Damon Wise: "We use all-copper cookware for the meat because it heats up fast and offers even heat distribution,” Wise explained. “You get a better sear on the meat and it cooks faster.” http://www.craftrestaurantsinc.com/craft-new-york/gallery/ Here are a bunch more chefs, as compiled by Matfer: http://www.matferbourgeatusa.com/chef-spotlight-brendan-collins And Chris Consentino of Cockscomb. -

Copper vs Stainless Steel Clad Cookware: Is it worth the $$$?

boilsover replied to a topic in Kitchen Consumer

Yes indeed, vessels that are strictly for heating or boiling thin liquids--the vapeurs, couscousiers, bain maries, chocolate and coffee kettles, poachers, etc.--needn't be thick. It doesn't hurt if they are, but thickness just doesn't make them work much better. The reason is that thin liquids develop very efficient convection currents. Thicken them up, though (or if you want to brown bones or sweat mirrepoix for your stock) and you'd better thicken the pan, too. FWIW, I can see value to having iron loop or ear handles on all these, rather than brass. The "ball peen" is called planishing, and is not ornamental, either. That beautiful hammered look actually hardens the copper, making it more resistant to dings and going out of round. Such "work hardening" is still valuable, even "today", as Falk and Mauviel press-form their pans. Your sauciers I would call 'Windsor', 'splayed saucepan' or a 'sauteuse evassee'. 'Saucier' as applied to cookware is a dubious modern term, and the pans which are called that are all over the board in terms of geometry. I think 'sauteuse bombee' would be a better name for the curved-wall "sauciers" being sold today. I have one small, single-pot copper and crockery bain marie. I have never miked the copper bottom, but it's quite thin. Ironically, mine was made by Waldow, to whose tooling Hammersmith and Brooklyn fell heir. Waldow once made a beautiful rotary bain marie holding multiple inserts; I'd like to have one. -

Copper vs Stainless Steel Clad Cookware: Is it worth the $$$?

paulraphael replied to a topic in Kitchen Consumer

Host's note: the following discussion was moved from the Brooklyn Copper Cookware topic. These are lovely as collector's pieces, but it would be foolish to expect any functional advantages over stainless-lined copper from Mauviel / Bourgeat / Falk (which are all essentially the same). And tin brings with it significant disadvantages. No matter what anyone tells you, it is fragile. In a saucepan you will abrade through it with a whisk if you whisk a lot (which you will if you are making things like emulsified egg sauces, which are arguably the only kinds of sauces delicate enough to demonstrate the benefits of copper). Forget about sautéing. A proper sear requires preheating above tin's melting point. The conduction differences in a metal layer that's less that 1/10mm are insignificant. There is no "non-stick" advantage to tin. If food sticks to your cookware, you've got technique issues. There are still a couple of places in the country that re-tin cookware. Look at $70+ for most pieces. Not a big deal if the cookware is decorative, but that will add up if you use the stuff hard. I wouldn't consider thickness beyond 2.5mm an advantage. You will get more heat retention and more evenness, but at the expense of slower responsiveness. And responsiveness is the real reason to use copper. You can get evenness and heat retention for miles from heavy aluminum, at a fraction the cost. Unless decoration is your primary concern, I would be wary of spending money on any copper. I love my 1.5L windsor pan because I'm a sauce geek, and because this pan is made for the things copper does best. But let's be honest ... look in the kitchens of Michelin 3-star restaurants around the world. If it isn't an open kitchen (on display) and if they bought their cookware this side of World War 2, they're probably using some kind of laminated stainless. The differences are vanishingly small in practice. I use my 2.5mm copper because I bought it when the stuff was pretty affordable. I also use laminated stainless / aluminum, disk-bottom aluminum, heavy aluminum, cast iron, spun steel. The laminates get the job done as well as the copper. They just don't look as awesome when they're doing it. If you work out the physics calculations, copper has an edge in some situations, but it's not going to influence your real world results. You could save the money and get an immersion circulator or pressure cooker or something that will give you serious new powers in the kitchen. -

The big box from Brooklyn Copper Cookware (BCC) arrived, and with anticipation I unpacked the 6 QT casserole + lid, and the 3 QT sauté pan. They are thick and heavy beautifully hand-made tin-lined 3mm copper pots with cast iron handles. Brooklyn Copper Cookware is on to something - these pots are very special indeed and BCC deserves hearty congratulations for producing these wonders! I am in awe - these are artisanal masterpieces, heirloom cookware that will make many wonderful meals during my lifetime and for generations to come. I can't wait to start cooking with them! BCC currently offers a selective range of products including a 3 QT sauté pan, a 3 QT rondeau, and a 6 QT casserole with a 10” lid that also fits on all of their current 9.5” diameter pots. They will be reintroducing a slightly smaller 14 QT version of their original 16 QT stock pot, and have announced the pending release of 1, 2, and 3 QT sauce pans: http://www.brooklyncoppercookware.com The Brooklyn Copper Cookware pots are more artisanal than my Mauviel pieces. The BCC pots are thick 3mm copper lined with tin, and they are entirely made by hand. My Mauviel pots & pans are all current production (acquired new in 2015) 2.5mm copper lined with SS, except for a tin-lined 11" rondeau which is 3.3mm thick. Mauviel is made on a larger scale with more automation, and so appear to be more modern than the BCC pots. If I could use a musical example to illustrate the similarities and differences between Mauviel and BCC: Imagine the Bach cello suites played on a modern cello with steel strings by Mstislav Rostropovich as opposed to Anner Bylsma playing a Stradivarius cello with gut strings. Rostropovich is appealing to more modern sensibilities in his style of playing, while Bylsma is striving for authenticity with a more historically informed performance practice that is as close as possible to what Bach would have heard. Both performances are superlative, engaging, and relevant - I enjoy them both immensely, and they both nourish the soul. To me Mauviel is akin to the more modern interpretation, and BCC is the more authentic and historically informed performance. They both have a place in my kitchen. I imagine that Mauviel made pots in say 1905 that were more comparable to what BCC makes today than to what Mauviel is currently producing. They have grown far beyond the operation they started in 1830, and have evolved into a modern interpretation of their artisanal roots. They are still a relatively small company owned and run by the 7th generation of the founding family, but they have a product range that appeals to multiple markets and price points, of which high-end copper is but one of their offerings. BCC on the other-hand is making a selective range of artisanal copper products by hand and without compromise. They are appealing to those cooks who want to reach the pinnacle of their craft, much as the Stradivarius workshop once did for musicians many generations ago.

-

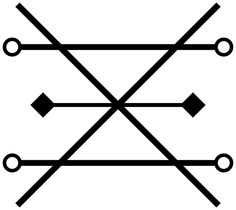

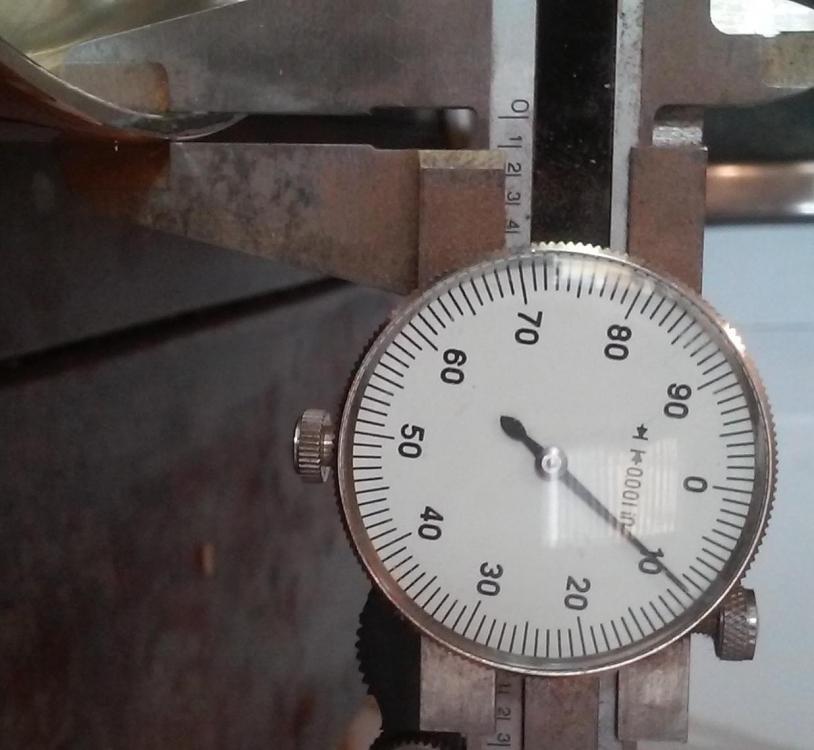

Brooklyn Copper Cookware 3 Quart Sauté—Worth the Wait Figure 1 -- It's here! The BCC Story A few years ago, what started as an arms-length business transaction with Brooklyn Copper Cookware blossomed into a friendship with its once and future owner, Mac Kohler. This was back when BCC’s production work was done with the help of Hammersmith. For those who don’t know, Hammersmith was heir to the old and well-worn machine tooling used to make the long-defunct Waldow lines of American copperware. From BCC’s founding, Mac has always had the passion and vision to make copper pans—top grade pans—in America again. BCC and Hammersmith succeeded in making very good wares, and developed a loyal following. What Mac did not have in those days was a means to produce true restaurant- and hotel-grade copper pans, what we collectors and the French cuisiners call “extra fort”. While “fort” at 2-2.5mm in thickness makes for good pans indeed, 2.4mm was the thickest metal the creaky Waldow hand-me-down tooling could handle. Even chefs and cooks who could justify dropping $400 on a single pan sometimes balked at a 2-something-mm sauté when there were 3-something-mm ones to be had. And, some sniffed, what does an American know about making the very best copper pans? What Mac also didn’t have was dependable production capacity to fill orders for BCC’s pans. This was partly due to the fact that Hammersmith’s work with pans was not their bread and butter—painstakingly making and fitting architectural metal in New York City rail stations was. It was also the case that skilled metalworkers were rare in Brooklyn. So orders lagged, customers started grumbling, and the copper snobs kept sniffing. When Hurricane Sandy, a major gas leak, and a lost lease conspired to halt production completely, BCC and Hammersmith went their separate ways, and it looked like the end. Passion is a marvelous thing. Mac had it, never lost it. It took him and his new partner, Lane Halley, years, blood, sweat and tears, to resurrect BCC. Mac turned to the heartland to find the materials, tooling, capacity and worker skill sets he would need to make extra fort pans, cast his handles, assemble them, and line their wares with tin. BCC utilized a top casting designer for what are destined to become iconic iron handles. It’s a success story within a success story: Not only are BCC’s pans American-made, they’re produced by metal crafters in America’s rust belt who kept these irreplaceable skills alive like a lost language. And, as you’ll read, while the BCC v2.0 pans are at least the equals of the greatest European makers’, they stand apart as unmistakably American in form. Fair disclosure: Mac gave me this pan to review. A Pan by the Numbers Figure 2 At present, the pans BCC offers (sauté, rondeau, casserole, and stockpot) are all 9.5” or 24cm in inside diameter. This number relates to the fact that all can be spun using the same 9.5” diameter lathe tooling. Sautés, unlike frypans, are sized not by diameter but volume; in this case the sauté is truthfully advertized as 3 quarts. However, putting 3 quarts in this pan entails raising a meniscus above the pan’s rim. One quart submerges a rivet, and two quarts would be all the liquid a jittery cook would ever put in it. The floor of the pan is 8.25” or almost 21cm in diameter. This sauté weighs 6.8 pounds, or roughly 3 kilos. Needless to say, this feels heavy, especially at the end of a handle—few cooks will be able to jump this pan one-handed. Fortunately however, BCC has paired it with both a long (10”/25.5cm) tongue and a loop helper handle. Much more on those in a minute, but for a pan this heavy, it’s been made as jumpable/shakable as possible. The pan stands 2 11/16” or 6.8cm tall at the walls. This yields a height-to-diameter ratio of 1:2.8, which is a classic proportion for sautés. Its total overall height, from underside to handle top, is only 5.75” or 14.7cm. This makes it easily stowable in short cupboards and shelving. The short handle rise also allows this sauté to hug within 4 inches of a wall when hung from a hook; compare this with over 6” protrusion for most classic sautés. Figure 3 --Note the Protrusion Difference When hung freely from an overhead rack, the pan only occupies 6” of horizontal space—a saving of 2 inches over my other sautés. However, the long tongue and helper handles together mean that the pan’s overall length is a surprising span of 22 inches. BCC states that its pans are made from full 1/8” copper foil. It also advertises that its pans are 3mm thick. Since 1/8” is almost 3.2mm, I asked Mac why BCC doesn’t tout the higher 3.2mm number. The answer came back that, while the foil itself is 3.175mm, the turning process moves material on the mandrel, effectively stretching and thinning the walls as the pan is formed up to the rim. My measurements verified that the sauté’s floor is indeed 3.2mm, and that the walls measured between 0.108 and 0.110 inches thick (2.74-2.8mm). Figure 4 -- Wall is 0.015" or 0.3mm thinner than floor At first glance, I was doubtful the walls were even 2.7mm thick, but the weight told me otherwise. On closer inspection, however, I found that both the inner and outer edges of the rims had been “broken”, or rounded over ever so slightly. This was, I was to discover, just the first of several classy finishing touches BCC gives its pans. Bottom line: Where it matters, this pan is 3.2mm. Figure 5 -- Still thick. Note gentle rounding of edges. BCC Has it Handled One thing that sets BCC apart is its unique, robust cast iron handle designs. Mac hired noted designer Barbara Stork to create something distinctive, yet completely functional. What BCC and its customers got were works of elevated art. These designs are so beautiful and detailed, in fact, that BCC chose to cast its mark in the handles rather than stamp it on the pan body (There is a designator mark “S3” stamped on). The tongue and helper handles on the sauté are unique to this pan (The rondeau, casserole and stockpot each have two different loop handles, and the universal cover also has a different tongue). Classical French sauté handles typically rise almost vertically from the flange and, after a curved section, climb in a straight line at a relatively steep rake of up to 40 degrees; a classic French sauté can have its loop end perched nine inches above the hob. This traditional design is good for leverage and carrying, but the vertical start makes cleaning the pinched space between handle and pan difficult. And a high handle oftentimes means the sauté won’t easily fit in an oven; even if it will, it must usually sit alone on a bottom rack, hogging the whole space. Potatoes go cold while the veal medallions finish… The BCC tongue handle solves both problems. Its shaft leaves the flange at a much lower angle, and there is a nice ¼” space left built in between the handle’s shaft and the pan wall, both of which eliminate that gunk-trapping crevice on other pans. Also, the BCC tongue itself is a compound curve, which allows it to sit lower overall. Figure 6 -- Note handle's compound curves. Depending on your oven, this may mean using your oven for more than one dish at a time, or being able to place your sauté on a middle rack. This alone is a big improvement. Figure 7 -- Finally, the pommes can stay in the oven! The BCC tongue gives up more surprises when you grasp it. For the first 2/3 of its length, it has a pronounced underside rib which makes the pan less “turny” when gripped over- and underhand. Figure 8 And the large hanging eye actually curves up over its final 1.5”. It took me several uses to realize this, but with an overhand grip, the heel of your hand fits comfortably into the little dish formed in the oversized eye; this helps with leverage. Figure 9 –Also a FigFigure 9 -- Also a pivot point Finally, the symbolic “mark” is on a raised rectangular cartouche, which doubles as a very nice thumb stop/rest when choking up on the handle. Figure 10 -- Alchemy for your kitchen. Note ample cleaning space between wall and handle. Wiccans reading this may recognize BCC’s mark as a fragment of the alchemical symbol for… copper (I didn’t. I had to ask.). Figure 11 – Your mark of quality and gnosis. I’ve never seen anything quite like the helper Stork designed for the BCC sauté. I think it looks like a leaf. I was skeptical at first about it, but after use, I think it’s very ergonomic. It is technically a bent loop, with room to accept a very large finger, but it also functions as an “ear” that can be securely grasped with a side towel or mitt. This is brilliant. Figure 12 The tongue handle is secured by 3 large rivets in an inverted classic offset pattern (contrast with Mauviel and Falk’s two). Figure 13 -- Classic pans have the one center rivet above, two flankers below. As you can see, even the handle flange got special attention. Rather than start with the traditional, boring blob-shaped flange, BCC and Stork imparted a little flair with a gentle point and swoops. The helper is held fast by two more husky rivets. Figure 14 – No bean-counting engineering here. All 5 rivets are decidedly stout, with a shaft diameter of 0.315” or just under 8mm. While the rivet heads are smaller than those monsters found on the best vintage European pans (and the Duparquet homages), they are substantially larger than those tiny blips used by Falk, Mauviel, Bourgeat and other modern makers. Figure 15 Finally, the handle castings are perfectly textured where they should be for grip, but smooth where they could bite or scratch. Tinning, Fit & Finish The lining arrived very bright, almost mirrored, a finish that I normally associate with electroplated tin. Figure 16 But a glance in good light reveals the sworl marks that come with a hand-wiped lining (more on this in a second). Figure 17 –Machines can’t do this. Ohioans can. I have no means of measuring the tin thickness, but I’m told this falls between 0.35mm and 0.45mm. Note that this is roughly twice as thick as the stainless linings in bimetal pans. BCC’s linings should last decades with proper utensils and care. The top surface of the rim was uniformly tinned, no mean feat considering the edges had been broken. I learned that this rounding of the edges is not merely a matter of comfort. It turns out that when sharp corners are tinned, the tin is prone to seize and come off when, e.g., a wooden spoon is rapped on the rim. I’ve personally experienced tinned rims blistering when nowhere else did; this may be why. The exterior arrived polished brightly, but well short of a mirror finish. In fact, the pattern imparted by the cutting rouge was still visible in good light. Having said that, this is definitely not a brushed finish like Falk’s. The fitment of rivets and handles is tight, square and flawless. I have never seen better. Finally, a wonkish word on hardening. This subject would not normally fall under finish but it belongs here for this pan. That is, traditionally, copper pans were worked to shape in stages, originally by hammering the soft metal. Hammering (a/k/a planishing) hardens the copper. This is good in a finished pan, but can be bad if there’s forming yet to be done, because hardened copper can crack when it’s worked. Coppersmiths learned that their work could be resoftened by heating, annealing the metal so it could be further worked to a pan’s final shape without cracking. Pound a little, anneal, pound some more, repeat. After forming, the best pans got a final session of planishing, intended to work harden the copper. Harder pans meant longer-lived, flatter pans, and so the planishing marks became recognizable signs of high quality. Uniform, interlocking patterns became the beautiful, prismatic “painting” on the “canvas” of the copper. BCC’s pans are obviously not planished, but they are work-hardened. Because they are spun on a lathe and formed in one fell swoop by a craftsman using his hands and ears, they get their hardening all at once, while they’re being made. BCC’s website explains this in deep detail; suffice it to say, stamped copper pans don’t get hardened this way, and the bimetal ones can’t be hardened by planishing—if it weren’t for the thin steel liner, they’d bend, warp and dent like crazy. The BCC craftsmen listen for the sounds the copper makes as they work it, and the art is in fully forming the pan just as the metal rings like a bell. The BCC pans needn’t be planished to be hardened. Ergo, planishing would be purely a cosmetic, expensive finish. Astute readers of BCC’s website might wonder as I did: If BCC applies linings after preheating its pans to 1200F, why aren’t they annealed back to soft and don’t they lose this work-hardening? The answer turns out to be that only the surface of the metal is brought to that perceived temperature, and much cooler (500F) molten tin is quickly ladled in to moderate the heat. Yet there’s enough stored heat left to keep all the tin flowing and get a good, thick, even wiped coating. This is yet another example of the craft required to make these pans correctly. Comparisons BCC’s website describes their pans as: “… merely the best and most beautiful copper cookware in history.” Now, I know Mac to be a temperate man, not prone to puffery, but is this objectively true? Is such a claim of the reasonable-minds-can-differ flavor, or is it pride and hyperbole? The only way I can judge is to compare this pan with the finest vintage copperware I own or have handled. I do not have another 24cm sauté, but my best extra fort sautés and rondeaux are three made by the famed house of Gaillard, one sauté a 22cm and the other a 28cm, and the rondeau a massive 36cm. I can objectively state that my Gaillards are thicker, close to 4mm bottoms. I can also say the Gaillards are marginally thicker in the walls, “miking” at between 3.0 and 3.1mm average (compared with this pan’s nominal 2.8mm thickness). Measuring these planished pans’ walls is uncertain to some degree, because the hammer blows push the copper about, making it thinner where the center of the hammer fell and thicker around the edges. Gaillard was also famous for intentionally tapering its walls toward the top—its pans were sometimes well under 3mm at their rims and much more than 3mm in the bottoms. But if greater thickness alone in a sauté equates with best ever, BCC may be fudging a little. However, Gaillard has been out of business for a long time. Other than a handful of tiny boutique ateliers, I don’t think anyone is making copper sauté pans any thicker than BCC’s. Interestingly, the 24cm BCC saute’s gentle shoulder radius means that the 8.25“/21cm floor is large enough for three of the enormous chicken breasts now dominating the consumer market. In comparison, my 22cm Gaillard, with more acute corners and a slightly smaller floor of 7.875”/19.7cm, would only fit two without crowding. In other words, the BCC pan cooks “bigger” than the 1cm floor size difference would indicate. I can also say that, poor cook that I am, and sautéing not happening on the walls, I can tell no performance difference between these pans. So any debate about “best” in this lofty class of pan necessarily devolves into a near-theological debate. To keep things real, if BCC’s pan is the thickest one you can buy new, and it ranks 99.7% (compared to 80% for best-in-class clad), and the only arguably “better” pan ranks 99.8%--and is unavailable—why isn’t BCC’s the best? I have no problem whatsoever judging the BCC sauté as attaining the finest level of fit, finish and ergonomics I’ve ever seen. Nothing else I’ve handled comes close. On the aesthetic side, the Stork handles are beautiful in ways that a classical pan’s handles have never been. In fairness, no one before lavished such design acumen and attention on functional handles for copper cookware. Simply as a matter of industrial design, these handles are masterpieces; if Alessi copied these handles in stainless steel for some Danish designer’s clad pans, they’d instantly be on display in MOMA. I confess I prefer the look of planished pans, and I still consider planishing a mark of quality. But I accede that it’s not a necessary condition for attaining work-hardening. There are also some touches on some vintage pans, e.g., stepped chamfering on the bottom/wall radius (barely visible in Figure 3), that I find particularly beautiful. Finally, the form of BCC’s pans is distinctly American even in ways that transcend those glorious, muscular Stork handles. I find intrinsic beauty in this, even if I can’t fully articulate all the style elements. The Beauty Marks This is the hardest part of this review to write. Far be it for me, a spectator and dilettante, to deign to tell BCC what it could do better. There are probably 100 reasons I’m wrong to quibble over minutia, and it’s all just my opinion, but here I go, telling Rembrandt how to paint… I find the overall length of 22 inches too long to fit on a crowded cooktop. I wish that—for a 24cm sauté—the tongue was shorter, and I may have omitted the helper on this size pan. For comparison, my 22cm Gaillard’s handle adds <7 inches to the pan’s overall length; if it were fitted to the BCC sauté, the OAL would be more like 16 inches overall. I wish BCC had found a way to employ inner rivet heads that sit flush with the pan wall. I put this in the “nice touch” category rather than a problem. The leverage could be better. Perhaps this is because I’m accustomed to high-rake, traditional handles, but the 6.8-pound, 24cm BCC pan feels more than 1 pound heavier than the 5.8-pound Gaillard 22cm. For my large hands, I wish the waist of the tongue handle had been kept a bit fatter—it still feels slightly “turny” like some Mauviel pieces. Figure 18 -- Handle waist viewed from beneath As long as I’m fantasizing, offering a silver-lined option would be nice. Make it thick Sheffield plate while you’re at it, Rembrandt. Final Words Upper 99th percentile in performance. Flawless fit and finish. Iconic styling. Versatile size. Designed and made in America by really good people. Immortal. Stunningly beautiful. The best pan of any kind available at retail. A value at $400. This pan will either make you cook better, or care about cooking more—in which case, you’re also likely to cook better. If consumers have any sense at all, BCC v2.0 will be a smashing success. To Learn More: Brooklyn Copper Cookware, Ltd. 687 Jay Street Brooklyn, NY 11201 (347) 866-2600 www.brooklyncoppercookware.com

-

Paul Revere Limited Editions vs Falk Copper Cookware

David A. Goldfarb replied to a topic in Kitchen Consumer

I've found the best way to find deals on heavy copperware is to look either for shops that are closing out their tin-lined copper, or look for second-hand pieces on eBay, particularly if they need retinning, and have them retinned if needed. Usually the need for retinning will frighten most buyers off, but it's really not that difficult to have done, nor is it extraordinarily expensive, particularly given the cost of the items. For instance, Zabar's and Bridge Kitchenware were both selling Mauviel heavy tin-lined copperware at 50% or greater markdowns compared to new stock for years, particularly on large pieces like stockpots. I bought my rondeau in the size you're considering for around $300 with lid as I recall. There's a seller on eBay ("harestew") who bought up a lot of the large pieces from Bridge before their most recent move and is selling them off piecemeal at a significant markup from what Bridge was asking, but for less than the new prices from sources like buycoppercookware.com. There are sometimes good prices on selected pieces of Mauviel copperware from metrokitchen.com You might keep an eye out for copperware made in Brooklyn, New York. Some of this stuff is developing a cult following, so it isn't always such a bargain, but the company now known as "Hammersmith" is actually an old U.S. manufacturer of copperware for the hotel and restaurant trade. Their main contract these days, I gather, is some kind of metal fabrication for the city of New York, but they have the old molds and patterns and make copper cookware on a small scale and sell it at Brooklyn Kitchen-- http://www.thebrooklynkitchen.com/ -

So soft opening to the public was last night. Reservations in the main dining room were booked until 10 so I walked in and got a seat in the bar/cafe area with three friends. The fact that these bar tables are not overseen by the host stand is a little bit perplexing. It gives the bar area more of a disorganized atmosphere that doesn't really benefit anyone. In addition to the usual masses of people stalking bar seats, you have parties stalking tables. It's kind of of awkward. I kind of lucked out in getting a bar seat right away for a pre-dinner drink while my friends quickly found a table. I could see this being very frustrating though, especially if you're not willing to be all eagle-eyed and pushy with the tables. The fact that couples took up four-tops and groups of three and four were forced to sit at tables for two doesn't seem all that efficient. I will say the space is rather striking. The dining room is set a little below street level and you immediately walk into this glass foyer that looks over the entire restaurant. The beer list and text scrawled and imprinted on the glass mirrors that circle the top of the room are all but illegible, making them kind of pointless. The much blogged pans from famous chefs across the world are cool I suppose but don't make much of an impression in this busy space. If you didn't know you'd be hard pressed to think they're any different than the copper cookware in any bistro or brasserie. Servers were harried but friendly. It was their first night so I'll cut them some slack, but our table was about the only one in the bar area that had to request both a bread basket (with our two plates of charcuterie) and a condiment rack (with out burgers and sausages). It's super busy so don't expect coddling. Our food came quickly, perhaps too quickly, but everything was prepared very well. The bar menu is a rather abbreviated version of the main dining room menu. Oyster, two types of charcuterie, three dogs, three burgers, some cheeses, and perhaps a salad. The variety of sausages and composed dishes available on the full menu are not offered in the bar. Still, we put together a well-rounded meal. There are a good number of well chosen beers on tap, but they're all rather expensive. A couple $6 selections, and it goes up from there. No $3 PBR cans or $5 Brooklyn Lager specials here. My favorite of the three burgers was actually the Yankee, the most basic of the lot. I felt as though the pork belly on the Frenchie and pulled pork on the Piggie were perhaps a bit distracting, though both were wholly enjoyable. The grind and cooking on both burgers was exemplary. Loosely formed, juicy, very tasty. Burgers are a few dollars more expensive than what was shown on preview menus, so while tasty they're not particularly cheap. To start we also tried the two charcuterie items on offer. Both were very good, but should be served with more than a single slice of crusty bread. The bread in the bread basket itself was, surprisingly, forgettable. The dogs were the weak point for me, and the DBGB dog was the weakest dish of the night. It was fine but the filling was too airy and smooth. If I'm being honest I find Thuuman's dogs to be much more flavorful and snappy. Also had the Tunisienne, a very skinny merguez sausage on a bun. Flavor was good, but the sausage itself was a bit dry; the bun-sausage ratio was a bit off which further contributed to the perceived dryness. Desserts were classic but really intense. The coffee ice cream in our chocolate-coffee sundaes was pleasantly bitter. The sweetness came from rich brownie squares that managed to shy away from being cloying. The souffle was technically great, with strong Grand Marnier flavor. Would like to try the Baked Alaska for two, but at $18 we weren't ready to take that risk on a somewhat bizarre sounding dessert. After tax, tip, and one beer I spent about $46. One could spend less, but not much less. Of course, the sky is the limit with premium items like the seafood towers and more expensive plated dishes available in the main dining room. I thought it was a good value given the level of quality in the ingredients and unimpeachable execution. Wish service was a bit less harried but that will hopefully work itself out in the coming weeks and months.

-

There is a metal fabrication shop in Brooklyn called Hammersmith making copperware in small quanitites as a side business and selling it mainly through a shop called The Brooklyn Kitchen. Their website seems to be under reconstruction at the moment, so they don't have much listed online, but here's one example-- http://www.thebrooklynkitchen.com/web-store/cookware/copper/hammersmith/195-copper-sauce-pan-18cm-wo-lid/ They have more pieces in the store, and prices are comparable to Mauviel professional tin-lined copperware. They currently have some big contract with the City to make some kind of utility boxes or manhole covers or something, but they used to be a major supplier of copperware to restaurants and hotels, so they have molds and forms and tooling on hand for these pieces.

-

Hi Everybody, It seems BCC/Hammersmith is now just Brooklyn Copper Cookware, and I called there to see if anyone remembered my case, or if it had come up again. I spoke to Mac, who did not remember my specific pan, but he said that he had seen this problem many times over the past 5 years. He did not want to guess how many, but in every case the pan was from Ross Dress 4 Less, Tuesday Morning, TJMaxx, or a few others. Mac had a little more information, so I thought I'd follow up on this thread. I think I took pretty good notes, but if you need more information call Mac (check the BCC website because their number is new) or your favorite retinner. Mac is sure the bad pans are not from the real manufacturers. Apparently it's very easy to have a metal stamp made and to fake tags. But the real issue has to do with low-priced copper sold in Europe. Inexpensive already lined pans and handles are imported to France as separate pieces and riveted together in France. This allows them to be legally stamped "made in France". At some point some bad pans lined with lead-laced tin were imported, but they were caught containing lead so could not be sold in Europe. Rather than return them, somebody bought everything really cheap and riveted them with cheap aluminum rivets (first sign of fraud) and shipped them to the US. Aluminum looks like tin on the inside of the pan, but you can see aluminum on the handle side too, and good French manufacturers usually use copper rivets. Mac said it makes sense that they got into the US easily, since customs sees copper cookware from France all the time. The importers sold the frauds wholesale through big conventions where buyers from discount stores buy. When they saw solid French copper for $20 (second fraud sign) they could sell for $40, they scooped it up. Mac said no one knows exactly where the bad pans came from, but in many places roofing tin (which has lead in it) is often sold as just tin, so it's probably somewhere with no tradition making copper cookware. BTW, acid is used to break down old tin for retinning a copper pan, not necessarily to test for lead. When a real tinned pan is dipped in acid it turns one color, and when there is lead it turns another color. I'm not sure that was clear in my previous post?

-

Congrats; it's excellent stuff. Still quite expensive, and hardly the "world's finest copper cookware", but hey, who expected them to tout Brooklyn Copper Cookware?