Search the Community

Showing results for tags 'Chinese'.

-

I've mentioned the craze for Luosifen which led to 6 million sheep following each other to Liuzhou over the CNY holiday to try a dish half of them hoped to hate. But it's not the only insane craze. Back in summer 1998, when I was living in Hunan, there was catastrophic flooding which wiped out the soy bean harvest. Thousands of farmers were hit by disaster. A couple of the more enterprising kind started making a kind of snack product using wheat flour rather than the hard-hit soya flour normally used in their cuisine. Basically they made wheat gluten strips which they slavered in chilli. These they called S: 辣条; T: 辣條 (là tiáo), 'spicy strips' and sold them outside schools for mere cents. Latiao - image from Meituan food delivery app. A billion dollar industry was born. Most of the customers were and still are schoolchildren who went crazy for the addictive if not nutritious snacks. According to an article in Global Times, China's uber-nationalist State-owned English language 'newspaper', latiao has gone viral globally. I don't believe a word of it. In China, yes. Globally? Have you or your children, grand-children, great-grand-children even heard, never mind fallen for this? For the record, I've never eaten them. A non-hysterical history of the craze is here. https://www.theworldofchinese.com/2024/02/stripped-down-the-story-behind-chinas-favorite-snack/

-

A side discussion on the Dinner 2024 topic promoted this. Chinese cooks, from the most elevated chefs to the home cook and all the way down to this crazy foreigner in their midst, swear by 鸡粉 (jī fěn), chicken powder. It is used to enhance or even make stocks or braising liquids; it is sprinkled on stir fries and other dishes like any other seasoning; it is added to drinks. I've even seen it added to cocktails. Anywhere umami is wanted. Knorr and other western brands can be found in China but are not particularly popular. Lee Kum Kee was mentioned but I've never seen that particular LKK product in China. KKK products, which I have never rated, are more popular abroad. So, I thought it may be useful to mention the most popular brands here, some of which are likely to be available in Asian markets. Before doing so, I will say that most Chinese brands unashamedly contain MSG. I have no intention of resurrecting that horse which is not only dead but has been utterly cremated, mourned, disinterred and reburied several times before. Nothing wrong with MSG. So, some brands. 厨邦 (chú bāng) means 'kitchen nation'. It is medium level brand with less of a pronounced flavour as some of the others below. Certainly not first choice. 大桥 (dà qiáo) means 'great bridge' and while their powder is fine I wouldn't extend that to 'great' among the following. 太太乐 (tài tai lè) Mrs Le. Mrs Happy is a popular brand which I happily put in second place. Umami rich with a good chicken flavor. 百家鲜 (bǎi jiā xiǎn) literally means '100 households' choice', but 百 also just means 'all kinds of'. All kinds of households' choice. It is certainly the biggest seller. It smells and tastes like roast chicken straight from the oven. I'd bet of the 96 apartments in my block, 90% have a pack in the kitchen. I buy it in 1kg tubs and am never without it. Restaurants buy it by the sack load.

-

China manufactures by far the majority of the world’s microwaves, but while it is true that many people in mainland China have them, very few are actually used for cooking. They are mostly seen as tools to reheat the last meal’s leftovers. Of all those microwaves, those capable of baking (convection microwaves) are a small percentage and three to five times more expensive. Even those who do own such things seldom bake in them and they can’t bake everything. There was a brief fashion about eight years ago for baking, but most people were using toaster ovens to bake Western style cakes. Nothing Chinese. Several shops opened selling the appropriate ingredients. 90% of them lasted a year or two at most. People moved on the next craze. The bookshops had a few Western style bakery cookbooks, but no longer.

-

Do a loose search for ‘Chinese Cuisine’ and often you’ll be directed to books or websites telling you that China has eight distinct cuisines. Unfortunately, this is yet another myth. The repetition of this ‘fact’ comes from the Imperial court stating such hundreds of years ago and it becoming a cliché, both in and out of China. The eight are usually listed as: 鲁菜 (lǔ cài), Shandong cuisine 粤菜 (yuè cài) Cantonese cuisine 川菜 (chuān cài) Sichuan cuisine 苏菜 (sū cài) Jiangsu cuisine 湘菜 (xiāng cài) Hunan cuisine 浙菜 (zhè cài) Zhejiang cuisine 徽菜 (huī cài) Anhui cuisine 闽菜 (mǐn cài) Fujian cuisine The list was compiled when China’s present day borders were somewhat different. In fact, not only are there many, many more; even within these categories there are distinctly different cuisines. Hunan, for example has three distinguishably different cuisines, as does Guangxi where I live. Also, the list excludes many more. It only includes the majority Han Chinese cuisines and excludes the ethnic minority cuisines of which there are so many. It also excludes significant cuisines such as Yunnan cuisine, Guizhou cuisine, Shaanxi cuisine, Xinjiang cuisine, Dongbei cuisine, Inner Mongolian cuisine, Tibetan cuisine and more. It doesn’t even include Beijing or Shanghai, both of which have their own distinct cuisines. Over the next few posts I will attempt to herd cats and describe some of the eight, but more of the others as they tend to be less well known out of China.

-

Chef Wang is one of my favorite YouTube channels, and a few weeks ago he got into trouble with the system. HERE is the CNN version of the story. HERE'S a slightly biased video explaining the cultural implications a bit more. My 5 second summary: A long-forgotten Chinese general was hiding in the mountains during a war, and decided to cook egg fried rice, which sent off smoke plumes that alerted the enemy of his whereabouts. Stupid mistake. So, if you cook egg fried rice near the end of September, when this incident happened, you are considered unpatriotic. Chef Wang released an egg fried rice video a few weeks ago, which is now gone from his play list. I saw the video and thought it was an odd step backwards in his repertoire, but he does do quite a bit of home cooking on top of his restaurant quality dishes. Was it on purpose? Who knows, but he apologized and said he would never release an egg fried rice video again. He hasn't posted any videos since. FWIW, he lightly argued that he releases numerous fried rice videos throughout the year, so this was just poorly timed. Well, I hope he's able to come back because quite frankly his channel was a wonderful gateway to Chinese culture, and the far vast majority of the world would have had no idea of the backstory had the Chinese government not alerted us to the gaff.

-

I should know the answer to this question but I don't. I've looked it up a dozen ways but can't come up with a solid answer. I know that when I make Hot & Sour Soup, I've only to soak the bean thread noodles for a few minutes in hot water and then I can cut them up and put them into the soup. However, what I am looking for is a noodle, but not a bean thread type, that I can either soak for a few minutes...or cook for only a few minutes...before adding it to a very last-minute combination of already cooked chicken, already made sauce, probably commercially frozen vegetables or defrosted already home-cooked ones. I do tend to roast and freeze a lot of vegetables. This is all for those times...of which there are increasingly more...when I am just too tired to make a proper meal. But we still want to eat non-processed foods. We don't buy or eat much in the way of processed foods. For instance, we've never eaten any of the M&M's entrees and have no intentions of doing so. And I've never bought spaghetti or enchilada sauce. Or salad dressings. Not making value judgements...it's just the way we have always eaten...even when Ed did most of the cooking at night and I had yet to learn how really. (Hated cooking and came from a Mother who hated cooking.) Thanks.

-

I am stopping over in Singapore for unfortunately only one night and have been reading up on the food, particularly hawker centres, and how to order it. I'm sure I would be able to get by with English and pointing but I find their crossroads culture fascinating and I always like to learn a tiny bit of the language wherever I go. So it is part practical, part cultural. I realize that I am not getting pronunciation from internet sources but I have started to compile information, that may be interesting to others here, in a text file. What other food-related language in Singapore do you know? Obviously much originated with Chinese, Malay, and other cultures and I would be interested in similarities/differences in the language. Rather than a total dump, here is what I have thus far on coffee and tea. Even more complicated than ordering coffee in Australia or at Starbucks! Kopi (coffee with condensed milk & sugar) Teh (tea with condensed milk & sugar) Kopi o (coffee with no condensed milk, still has sugar) Teh o (tea with no condensed milk, still has sugar) Kopi o kosong (coffee with no condensed milk & no sugar) Teh o kosong (tea with no condensed milk & no sugar) Teh c (tea with evaporated milk & sugar) Tak giu (Milo) Diao yu (tea bag in hot water) Ditlo - no water added to your coffee or tea Kosong (no sugar, usually for beverages) Siew dai - less sweet Siew siew dai - less than siew dai (Malay stall usually go with ‘kurang manis’ than ‘siew dai’) Peng (Bing) (beverage with ice, Eg. kopi peng, teh peng) Teh tarik: Pulled tea. It is the national drink of Malaysia (Indian origin)

-

Having cooked meals and ingredients etc delivered to your office or home is hugely popular here in China. The biggest supplier is Meituan and you see dozens of their electric scooters dashing around every day. There isn't much you can't buy (anything from a raw egg to flock of live ostriches) and delivery is usually within 30 minutes. I have eaten from this source before but today was my first time to order for myself. This issue is due to my being confined to bed in a hospital with a more than usually dysfunctional kitchen. Anyway, here is my introductory dish. Spicy cumin beef fried rice with a vegetable soup from heaven The broth was indescribable. These dishes are from Lanzhou in NW China. Those who know the China Food Myths topic will note the lack of egg in the fried rice Cost me 26 cents US / 22 pence UK. This includes a huge welcome discount. The regular price is about 12 times that.

-

Sea fish in my local supermarket In the past I've started a few topics focusing on categorised food types I find in China. I’ve done Mushrooms and Fungi in China Chinese Vegetables Illustrated Sugar in China Chinese Herbs and Spices Chinese Pickles and Preserves Chinese Hams. I’ve enjoyed doing them as I learn a lot and I hope that some people find them useful or just interesting. One I’ve always resisted doing is Fish etc in China. Although it’s interesting and I love fish, it just felt too complicated. A lot of the fish and other marine animals I see here, I can’t identify, even if I know the local name. The same species may have different names in different supermarkets or wet markets. And, as everywhere, a lot of fish is simply mislabelled, either out of ignorance or plain fraud. However, I’ve decided to give it a go. I read that 60% of fish consumed in China is freshwater fish. I doubt that figure refers to fresh fish though. In most of China only freshwater fish is available. Seawater fish doesn’t travel very far inland. It is becoming more available as infrastructure improves, but it’s still low. Dried seawater fish is used, but only in small quantities as is frozen food in general. I live near enough the sea to get fresh sea fish, but 20 years ago when I lived in Hunan I never saw it. Having been brought up yards from the sea, I sorely missed it. I’ll start with the freshwater fish. Today, much of this is farmed, but traditionally came from lakes and rivers, as much still does. Most villages in the rural parts have their village fish pond. By far the most popular fish are the various members of the carp family with 草鱼 (cǎo yú) - Ctenopharyngodon idella - Grass Carp being the most raised and consumed. These (and the other freshwater fish) are normally sold live and every supermarket, market (and often restaurants) has ranks of tanks holding them. Supermarket Freshwater Fish Tanks You point at the one you want and the server nets it out. In markets, super or not, you can either take it away still wriggling or, if you are squeamish, the server will kill, descale and gut it for you. In restaurants, the staff often display the live fish to the table before cooking it. These are either steamed with aromatics – garlic, ginger, scallions and coriander leaf / cilantro being common – or braised in a spicy sauce or, less often, a sweet and sour sauce or they are simply fried. It largely depends on the region. Note that, in China, nearly all fish is served head on and on-the-bone. 草鱼 (cǎo yú) - Ctenopharyngodon idella - grass carp More tomorrow.

-

Way back in the 1990’s, I was living in west Hunan, a truly beautiful part of China. One day, some colleagues suggested we all go for lunch the next day, a Saturday. Seemed reasonable to me. I like a bit of lunch. “OK. We’ll pick you up at 7 am.” “Excuse me? 7 am for lunch? “Yes. We have to go by car.” Well, of course, they finally picked me up at 8.30, drove in circles for an hour trying to find the guy who knew the way, then headed off into the wilds of Hunan. We drove for hours, but the scenery was beautiful, and the thousand foot drops at the side of the crash barrier free road as we headed up the mountains certainly kept me awake. After an eternity of bad driving along hair-raising roads which had this old atheist praying, we stopped at a run down shack in the middle of nowhere. I assumed that this was a temporary stop because the driver needed to cop a urination or something, but no. This was our lunch venue. We shuffled into one of the two rooms the shack consisted of and I distinctly remember that one of my hosts took charge of the lunch ordering process. “We want lunch for eight.” There was no menu. The waitress, who was also the cook, scuttled away to the other room of the shack which was apparently a kitchen. We sat there for a while discussing the shocking rise in bean sprout prices and other matters of national importance, then the first dish turned up. A pile of steaming hot meat surrounded by steaming hot chillies. It was delicious. “What is this meat?” I asked. About half of the party spoke some English, but my Chinese was even worse than it is now, so communications weren’t all they could be. There was a brief (by Chinese standards) meeting and they announced: “It’s wild animal.” Over the next hour or so, several other dishes arrived. They were all piles of steaming hot meat surrounded by steaming hot chillies, but the sauces and vegetable accompaniments varied. And all were very, very good indeed. “What’s this one?” I ventured. “A different wild animal.” “And this?” “Another wild animal.” “And this?” “A wild animal which is not the wild animal in the other dishes” I wandered off to the kitchen, as you can do in rural Chinese restaurants, and inspected the contents of their larder, fridge, etc. No clues. I returned to the table with a bit of an idea. “Please write down the Chinese names of all these animals we have eaten. I will look in my dictionary when I get home.” They looked at each other, consulted, argued and finally announced: “Sorry! We don’t know in Chinese either. “ Whether that was true or just a way to get out of telling me what I had eaten, I’ll never know. I certainly wouldn’t be able to find the restaurant again. This all took place way back in the days before digital cameras, so I have no illustrations from that particular meal. But I’m guessing one of the dishes was bamboo rat. No pandas or tigers were injured in the making of this post

-

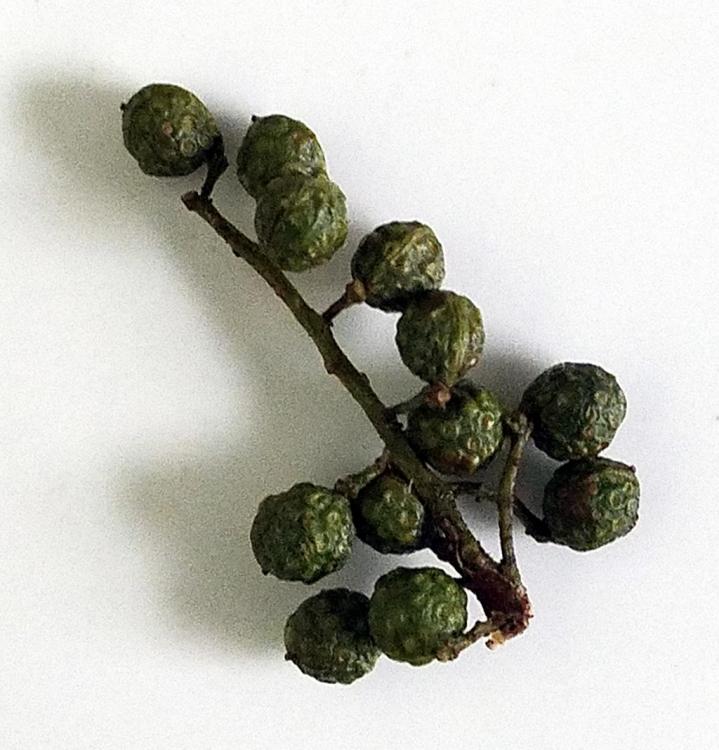

Your wish is my command! Sometimes! A lot of what I say here, I will have already said in scattered topics across the forums, but I guess it's useful to bring it all into one place. First, I want to say that China uses literally thousands of herbs. But not in their food. Most herbs are used medicinally in Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), often in their dried form. Some of the more common are sold in supermarkets, but more often in pharmacies or small specialist stores. I also often see people on the streets with baskets of unidentified greenery for sale - but not for dinner. The same applies to spices, although more spices are used in a culinary setting than are herbs. I’ll start with Sichuan peppercorns as these are what prompted @Tropicalsenior to suggest the topic. 1. Sichuan Peppercorns Sichuan peppercorns are neither pepper nor, thank the heavens, c@rn! Nor are they necessarily from Sichuan. They are actually the seed husks of one of a number of small trees in the genus Zanthoxylum and are related to the citrus family. The ‘Sichuan’ name in English comes from their copious use in Sichuan cuisine, but not necessarily where they are grown. Known in Chinese as 花椒 (huājiāo), literally ‘flower pepper’’, they are also known as ‘prickly ash’ and, less often, as ‘rattan pepper’. The most common variety used in China is 红花椒 (hóng huā jiāo) or red Sichuan peppercorn, but often these are from provinces other than Sichuan, especially Gansu, Sichuan’s northern neighbour. They are sold all over China and, ground, are a key ingredient in “five-spice powder” mixes. They are essential in many Sichuan dishes where they contribute their numbing effect to Sichuan’s 麻辣 (má là), so-called ‘hot and numbing’ flavour. Actually the Chinese is ‘numbing and hot’. I’ve no idea why the order is reversed in translation, but it happens a lot – ‘hot and sour’ is actually ‘sour and hot’ in Chinese! The peppercorns are essential in dishes such as 麻婆豆腐 (má pó dòu fǔ) mapo tofu, 宫保鸡丁 (gōng bǎo jī dīng) Kung-po chicken, etc. They are also used in other Chinese regional cuisines, such as Hunan and Guizhou cuisines. Red Sichuan peppercorns can come from a number of Zanthoxylum varieties including Zanthoxylum simulans, Zanthoxylum bungeanum, Zanthoxylum schinifolium, etc. Red Sichuan Peppercorns Another, less common, variety is 青花椒 (qīng huā jiāo) green Sichuan peppercorn, Zanthoxylum armatum. These are also known as 藤椒 (téng jiāo). This grows all over Asia, from Pakistan to Japan and down to the countries of SE Asia. This variety is significantly more floral in taste and, at its freshest, smells strongly of lime peel. These are often used with fish, rabbit, frog etc. Unlike red peppercorns (usually), the green variety are often used in their un-dried state, but not often outside Sichuan. Green Sichuan Peppercorns Fresh Green Sichuan Peppercorns I strongly recommend NOT buying Sichuan peppercorns in supermarkets outside China. They lose their scent, flavour and numbing quality very rapidly. There are much better examples available on sale online. I have heard good things about The Mala Market in the USA, for example. I buy mine in small 30 gram / 1oz bags from a high turnover vendor. And that might last me a week. It’s better for me to restock regularly than to use stale peppercorns. Both red and green peppercorns are used in the preparation of flavouring oils, often labelled in English as 'Prickly Ash Oil'. 花椒油 (huā jiāo yóu) or 藤椒油 (téng jiāo yóu). The tree's leaves are also used in some dishes in Sichuan, but I've never seen them out of the provinces where they grow. A note on my use of ‘Sichuan’ rather than ‘Szechuan’. If you ever find yourself in Sichuan, don’t refer to the place as ‘Szechuan’. No one will have any idea what you mean! ‘Szechuan’ is the almost prehistoric transliteration of 四川, using the long discredited Wade-Giles romanization system. Thomas Wade was a British diplomat who spoke fluent Mandarin and Cantonese. After retiring as a diplomat, he was elected to the post of professor of Chinese at Cambridge University, becoming the first to hold that post. He had, however, no training in theoretical linguistics. Herbert Giles was his replacement. He (also a diplomat rather than an academic) completed a romanization system begun by Wade. This became popular in the late 19th century, mainly, I suggest, because there was no other! Unfortunately, both seem to have been a little hard of hearing. I wish I had a dollar for every time I’ve been asked why the Chinese changed the name of their capital from Peking to Beijing. In fact, the name didn’t change at all. It had always been pronounced with /b/ rather than /p/ and /ʤ/ rather than /k/. The only thing which changed was the writing system. In 1958, China adopted Pinyin as the standard romanization, not to help dumb foreigners like me, but to help lower China’s historically high illiteracy rate. It worked very well indeed, Today, it is used in primary schools and in some shop or road signs etc., although street signs seldom, if ever, include the necessary tone markers without which it isn't very helpful. A local shopping mall. The correct pinyin (with tone markers) is 'dōng dū bǎi huò'. But pinyin's main use today is as the most popular input system for writing Chinese characters on computers and cell-phones. I use it in this way every day, as do most people. It is simpler and more accurate than older romanizations. I learned it in one afternoon. I doubt anyone could have done that with Wade-Giles. Pinyin has been recognised for over 30 years as the official romanization by the International Standards Organization (ISO), the United Nations and, believe it or not, The United States of America, along with many others. Despite this recognition, old romanizations linger on, especially in America. Very few people in China know any other than pinyin. 四川 is 'sì chuān' in pinyin.

-

According to the 2010 census, there were officially 1,830,929 ethnic Koreans living in China and recognised as one of China’s 56 ethnic groups. The largest concentration is in Yanbian Korean Autonomous Prefecture, Jilin Province, in the north-east bordering - guess where – North Korea. They have been there for centuries. The actual number today is widely believed to be higher, with some 4 to 5 thousand recent refugees living there illegally. Anyway, what I have just taken delivery of is this Korean blood and glutinous rice sausage from Yanbian. I am an inveterate blood sausage fiend and always eager to try new examples from as many places as possible. I'll cook some tomorrow morning for breakfast and report back.

-

I've recently become aware of the existence of this chain of Xi'an restaurants in NewYork. Are there more elsewhere? They were recenty referenced in a BBC article about biang biang noodles.

-

Following my posting a supermarket bought roast rabbit in the Dinner topic, @Anna N expressed her surprise at my local supermarkets selling such things just like in the west supermarkets sell rotisserie chickens. I promised to photograph the pre-cooked food round these parts. I can't identify them all, so have fun guessing! Rabbit Chicken x 2 Duck Chicken feet Duck Feet Pig's Ear Pork Intestine Rolls Stewed River Snails Stewed Duck Feet (often served with the snails above) Beef Pork Beijing Duck gets its own counter. More pre-cooked food to come. Apologies for some bady lit images - I guess the designers didn't figure on nosy foreigners inspecting the goods and disseminating pictures worldwide.

-

Yesterday, an old friend sent me a picture of her family dinner, which she prepared. She was never much of a cook, so I was a bit surprised. It's the first I've seen her cook in 25 years. Here is the spread. I immediately zoomed in on one dish - the okra. For the first 20-odd years I lived in China, I never saw okra - no one knew what it was. I managed to find its Chinese name ( 秋葵 - qiū kuí) in a scientific dictionary, but that didn't help. I just got the same blank looks. Then about 3 years ago, it started to creep into a few supermarkets. At first, they stocked the biggest pods they could find - stringy and inedible - but they worked it out eventually. Now okra is everywhere. I cook okra often, but have never seen it served in China before (had it down the road in Vietnam, though) and there are zero recipes in any of my Chinese language cookbooks. So, I did the sensible thing and asked my friend how she prepared it. Here is her method. 1. First bring a pan of water to the boil. Add the washed okra and boil for two minutes. Drain. 2. Top and tail the pods. Her technique for that is interesting. 3. Finely mince garlic, ginger, red chilli and green onion in equal quantities. Heat oil and pour over the prepared garlic mix. Add a little soy sauce. 4. Place garlic mix over the okra and serve. When I heard step one, I thought she was merely blanching the vegetable, but she assures me that is all the cooking it gets or needs, but she did say she doesn't like it too soft. Also, I should have mentioned that she is from Hunan province so the red chilli is inevitable. Anyway, I plan to make this tomorrow. I'm not convinced, but we'll see. to be continued

-

Two of my family members are pescetarian, one of whom is my picky daughter who only likes a few types of fish cooked in very specific ways so to all intents and purposes is mostly vegetarian. Many Chinese soup recipes involve meat or fish, or at least meat broth, so I'd love to find a few more recipes that would suit my whole family (I also don't eat much pork as it doesn't always agree with me, and a lot of soups involve pork so this is also for my benefit!). Vegetarian would be best, or pescetarian soups that are not obviously seafood based (I could get away with sneaking a small amount of dried shrimp in, for instance, but not much more than that!). Any kind of soup will do, although I'd particularly like some simple recipes that could be served alongside a multi-dish meal. But I'm always interested in new recipes so any good soup recipes would be welcome! Any suggestions?

-

Chinese food must be among the most famous in the world. Yet, at the same time, the most misunderstood. I feel sure (hope) that most people here know that American-Chinese cuisine, British-Chinese cuisine, Indian-Chinese cuisine etc are, in huge ways, very different from Chinese-Chinese cuisine and each other. That's not what I want to discuss. Yet, every day I still come across utter nonsense on YouTube videos and Facebook about the "real" Chinese cuisine, even from ethnically Chinese people (who have often never been in China). Sorry YouTube "influencers", but sprinkling soy sauce or 5-spice powder on your cornflakes does not make them Chinese! So what is the "authentic" Chinese food? Well, like any question about China, there are several answers. It is not surprising that a country larger than western Europe should have more than one typical culinary style. Then, we must distinguish between what you may be served in a large hotel dining room, a small local restaurant, a street market stall or in a Chinese family's home. That said, in this topic, I want to attempt to debunk some of the more prevalent myths. Not trying to start World War III. But don't get me started on Crab Frigging Rangoon! When I moved to China from the UK 25 years ago, I had my preconceptions. They were all wrong. Sweet and sour pork with egg fried rice was reported to be the second favourite dish in Britain, and had, of course, to be preceded by a plate of prawn/shrimp crackers. All washed down with a lager or three. Yet, in that quarter of a century, I've seldom seen a prawn cracker; they are Indonesian, not Chinese. And egg fried rice is usually eaten as a quick dish on its own, not usually as an accompaniment to main courses. Every menu featured a starter of prawn/shrimp toast which I have never seen in mainland China - just once in Hong Kong. But first, one myth needs to be dispelled. The starving Chinese! When I was a child I was encouraged to eat the particularly nasty bits on the plate by being told that the starving Chinese would lap them up. My suggestion that we could post it to them never went down too well. At that time (the late fifties) there was indeed a terrible famine in China (almost entirely manmade (Maomade)). When I first arrived in China, it was after having lived in Soviet Russia and I expected to see the same long lines of people queuing up to buy nothing very much in particular. Instead, on my first visit to a market (in Hunan Province), I was confronted with a wider range of vegetables, seafood, meat and assorted unidentified frying objects than I have ever seen anywhere else. And it was so cheap I couldn't convert to UK pounds or any other useful currency. I'm going to start with some of the simpler issues - later it may get ugly! 1. Chinese people eat everything with chopsticks. No, they don't! Most things, yes, but spoons are also commonly used in informal situations. I recently had lunch in a university canteen. It has various stations selling different items. I found myself by the fried rice stall and ordered some Yangzhou fried rice. Nearly all the students and faculty sitting near me were having the same. I was using my chopsticks to shovel the food in, when I noticed that I was the only one doing so. Everyone else was using spoons. On investigating, I was told that the lunch break is so short at only two-and-a-half hours that everyone wants to eat quickly and rush off for their compulsory siesta. I've also seen claims that people eat soup with chopsticks. Nonsense. While people use chopsticks to pick out choice morsels from the broth, they will drink the soup by lifting their bowl to their mouths like cups. They ain't dumb! Anyway, with that very mild beginning, I'll head off and think which on my long list will be next. Thanks to @KennethT for advice re American-Chinese food.

-

China's favorite urinating “tea pet” is actually a thermometer.

-

Big Plate Chicken - 大盘鸡 (dà pán jī) This very filling dish of chicken and potato stew is from Xinjiang province in China's far west, although it is said to have been invented by a visitor from Sichuan. In recent years, it has become popular in cities across China, where it is made using a whole chicken which is chopped, with skin and on the bone, into small pieces suitable for easy chopstick handling. If you want to go that way, any Asian market should be able to chop the bird for you. Otherwise you may use boneless chicken thighs instead. Ingredients Chicken chopped on the bone or Boneless skinless chicken thighs 6 Light soy sauce Dark soy sauce Shaoxing wine Cornstarch or similar. I use potato starch. Vegetable oil (not olive oil) Star anise, 4 Cinnamon, 1 stick Bay leaves, 5 or 6 Fresh ginger, 6 coin sized slices Garlic. 5 cloves, roughly chopped Sichuan peppercorns, 1 tablespoon Whole dried red chillies, 6 -10 (optional). If you can source the Sichuan chiles known as Facing Heaven Chiles, so much the better. Potatoes 2 or 3 medium sized. peeled and cut into bite-sized pieces Carrot. 1, thinly sliced Dried wheat noodles. 8 oz. Traditionally, these would be a long, flat thick variety. I've use Italian tagliatelle successfully. Red bell pepper. 1 cut into chunks Green bell pepper, 1 cut into chunks Salt Scallion, 2 sliced. Method First, cut the chicken into bite sized pieces and marinate in 1½ teaspoons light soy sauce, 3 teaspoons of Shaoxing and 1½ teaspoons of cornstarch. Set aside for about twenty minutes while you prepare the rest of the ingredients. Heat the wok and add three tablespoons cooking oil. Add the ginger, garlic, star anise, cinnamon stick, bay leaves, Sichuan peppercorns and chilies. Fry on a low heat for a minute or so. If they look about to burn, splash a little water into your wok. This will lower the temperature slightly. Add the chicken and turn up the heat. Continue frying until the meat is nicely seared, then add the potatoes and carrots. Stir fry a minute more then add 2 teaspoons of the dark soy sauce, 2 tablespoons of the light soy sauce and 2 tablespoons of the Shaoxing wine along with 3 cups of water. Bring to a boil, then reduce to medium. Cover and cook for around 15-20 minutes until the potatoes are done. While the main dish is cooking, cook the noodles separately according to the packet instructions. Reserve some of the noodle cooking water and drain. When the chicken and potatoes are done, you may add a little of the noodle water if the dish appears on the dry side. It should be saucy, but not soupy. Add the bell peppers and cook for three to four minutes more. Add scallions. Check seasoning and add some salt if it needs it. It may not due to the soy sauce and, if in the USA, Shaoxing wine. Serve on a large plate for everyone to help themselves from. Plate the noodles first, then cover with the meat and potato. Enjoy.

-

Beef with Bitter Melon - 牛肉苦瓜 The name may be off-putting to many people, but Chinese people do have an appreciation for bitter tastes and anyway, modern cultivars of this gourd are less bitter than in the past. Also, depending on how it's cooked, the bitterness can be mitigated. I'll admit that I wasn't sure at first, but have grown to love it. Note: "Beef with Bitter Melon (牛肉苦瓜 )" or "Bitter Melon with Beef (苦瓜牛肉)"? One Liuzhou restaurant I know has both on its menu! In Chinese, the ingredient listed first is the one there is most of, so, "beef with bitter melon" is mainly beef, whereas "bitter melon with beef" is much more a vegetable dish with just a little beef. This recipe is for the beefier version. To make the other version, just half the amount of beef and double the amount of melon. Ingredients Beef. One pound. Flank steak works best. Slice thinly against the grain. Bitter Melon. Half a melon. You can use the other half in a soup or other dish. Often available in Indian markets or supermarkets. Salted Black Beans. One tablespoon. Available in packets from Asian markets and supermarkets, these are salted, fermented black soy beans. They are used as the basis for 'black bean sauce', but we are going to be making our own sauce! Garlic. 6 cloves Cooking oil. Any vegetable oil except olive oil Shaoxing wine. See method Light soy sauce. One tablespoon Dark soy sauce. One teaspoon White pepper. See method Sesame oil. See method Method Marinate the beef in a 1/2 tablespoon of light soy sauce with a splash of Shaoxing wine along with a teaspoon or so of cornstarch or similar (I use potato starch). Stir well and leave for 15-30 minutes. Cut the melon(s) in half lengthwise and, using a teaspoon, scrape out all the seeds and pith. The more pith you remove, the less bitter the dish will be. Cut the melon into crescents about 1/8th inch wide. Rinse the black beans and drain. Crush them with the blade of your knife, then chop finely. Finely chop the garlic. Stir fry the meat in a tablespoon of oil over a high heat until done. This should take less than a minute. Remove and set aside. Add another tablespoon of oil and reduce heat to medium. fry the garlic and black beans until fragrant then add the bitter melon. Continue frying until the melon softens. then add a tablespoon of Shaoxing wine and soy sauces. Finally sprinkle on white pepper to taste along with a splash of sesame oil. Return the meat to the pan and mix everything well. Note: If you prefer the dish more saucy, you can add a tablespoon or so of water with the soy sauces. Serve with plained rice and a stir-fried green vegetable of choice.

-

Stir-fried Squid with Snow Peas - 荷兰豆鱿鱼 Another popular restaurant dish that can easily be made at home. The only difficult part (and it's really not that difficult) is preparing the squid. However, your seafood purveyor should be able to do that for you. I have given details below. Ingredients Fresh squid. I tend to prefer the smaller squid in which case I allow one or two squid per person, depending on what other dishes I'm serving. You could use whole frozen squid if fresh is unavailable. Certainly not dried squid. Snow peas aka Mange Tout. Sugar snap peas can also be used. The final dish should be around 50% squid and 50% peas, so an amount roughly equivalent to the squid in bulk is what you are looking for. De-string if necessary and cut in half width-wise. Cooking oil. I use rice bran oil, but any vegetable cooking oil is fine. Not olive oil, though. Garlic. I prefer this dish to be rather garlicky so I use one clove or more per squid. Adjust to your preference. Ginger. An amount equivalent to that of garlic. Red Chile. One or two small hot red chiles. Shaoxing wine. See method. Note: Unlike elsewhere, Shaoxing wine sold in N. America is salted. So, cut back on adding salt if using American sourced Shaoxing. Oyster sauce Sesame oil (optional) Salt Preparing the squid The squid should be cleaned and the tentacles and innards pulled out and set aside while you deal with the tubular body. Remove the internal cartilage / bone along with any remaining innards. With a sharp knife remove the "wings" then slit open the tube by sliding your knife inside and cutting down one side. Open out the now butterflied body. Remove the reddish skin (It is edible, but removing it makes for a nicer presentation. It peels off easily.) Again, using the sharp knife cut score marks on the inside at 1/8th of an inch intervals being careful not to cut all the way through. Then repeat at right angles to the original scoring, to give a cross-hatch effect. Do the same to the squid wings. Cut the body into rectangles roughly the size of a large postage stamp. Separate the tentacles from the innards by feeling for the beak, a hard growth just above the tentacles and at the start of the animal's digestive tract. Dispose of all but the tentacles. If they are long, half them. Wash all the squid meat again. Method There are only two ways to cook squid and have it remain edible. Long slow cooking (an hour or more) or very rapid (a few seconds) then served immediately. Anything else and you'll be chewing on rubber. So that is why I am stir frying it. Few restaurants get this right, so I mainly eat it at home. Heat your wok and add oil. Have a cup of water to the side. Add the garlic, ginger and chile. Should you think it's about to burn, throw in a little of that water. It will evaporate almost immediately but slow down some of the heat. As soon as you can smell the fragrance of the garlic and ginger, add the peas and salt and toss until the peas are nearly cooked (Try a piece to see!). Almost finally, add the squid with a tablespoon of the Shaoxing and about the same of oyster sauce. Do not attempt to add the oyster sauce straight from the bottle. The chances of the whole bottle emptying into your dinner is high! Believe me. I've been there! The squid will curl up and turn opaque in seconds. It's cooked. Sprinkle with a teaspoon of so of sesame oil (if used) and serve immediately!

-

Clam Soup with Mustard Greens - 车螺芥菜汤 This is a popular, light but peppery soup available in most restaurants here (even if its not listed on the menu). Also, very easy to make at home. Ingredients Clams. (around 8 to 10 per person. Some restaurants are stingy with the clams, but I like to be more generous). Fresh live clams are always used in China, but if, not available, I suppose frozen clams could be used. Not canned. The most common clams here are relatively small. Littleneck clams may be a good substitute in terms of size. Stock. Chicken, fish or clam stock are preferable. Stock made from cubes or bouillon powder is acceptable, although fresh is always best. Mustard Greens. (There are various types of mustard green. Those used here are 芥菜 , Mandarin: jiè cài; Cantonese: gai choy). Use a good handful per person. Remove the thick stems, to be used in another dish.) Garlic. (to taste) Chile. (One or two fresh hot red chiles are optional). Salt. MSG (optional). If you have used a stock cube or bouillon powder for the stock, omit the MSG. The cubes and power already have enough. White pepper (freshly ground. I recommend adding what you consider to be slightly too much pepper, then adding half that again. The soup should be peppery, although of course everything is variable to taste.) Method Bring your stock to a boil. Add salt to taste along with MSG if using. Finely chop the garlic and chile if using. Add to stock and simmer for about five minutes. Make sure all the clams are tightly closed, discarding any which are open - they are dead and should not be eaten. The clams will begin to pop open fairly quickly. Remove the open ones as quickly as possible and keep to one side while the others catch up. One or two clams may never open. These should also be discarded. When you have all the clams fished out of the boiling stock, roughly the tear the mustard leaves in two and drop them into the stock. Simmer for one minute. Put all the clams back into the stock and when it comes back to the boil, take off the heat and serve.

-

Hello everyone, This is my first post, so please tell me if I've made any mistakes. I'd like to learn the ropes as soon as possible. I first learned of this cookbook from The Mala Market, easily the best online source of high-quality Chinese ingredients in the west. In the About Us page, Taylor Holiday (the founder of Mala Market) talks about the cookbooks that inspired her. This piqued my interest and sent me down a long rabbit hole. I'm attempting to categorically share everything I've found about this book so far. Reading it online Early in my search, I found an online preview (Adobe Flash required). It shows you the first 29 pages. I've found people reference an online version you can pay for on the Chinese side of the internet. But to my skills, it's been unattainable. The Title Because this book was never sold in the west, the cover, and thus title, were never translated to English. Because of this, when you search for this book, it'll have several different names. These are just some versions I've found online - typos included. Sichuan (China) Cuisine in Both Chinese and English Si Chuan(China) Cuisinein (In English & Chinese) China Sichuan Cuisine (in Chinese and English) Chengdu China: Si Chuan Ke Xue Ji Shu Chu Ban She Si Chuan(China) Cuisinein (Chinese and English bilingual) 中国川菜:中英文标准对照版 For the sake of convenience, I'll be referring to the cookbook as Sichuan Cuisine from now on. Versions There are two versions of Sichuan Cuisine. The first came out in 2010 and the second in 2014. In an interview from Flavor & Fortune, a (now defunct) Chinese cooking magazine, the author clarifies the differences. That is all of the information I could find on the differences. Nothing besides that offhanded remark. The 2014 edition seems to be harder to source and, when available, more expensive. Author(s) In the last section, I mentioned an interview with the author. That was somewhat incorrect. There are two authors! Lu Yi (卢一) President of Sichuan Tourism College, Vice Chairman of Sichuan Nutrition Society, Chairman of Sichuan Food Fermentation Society, Chairman of Sichuan Leisure Sports Management Society Du Li (杜莉) Master of Arts, Professor of Sichuan Institute of Tourism, Director of Sichuan Cultural Development Research Center, Sichuan Humanities and Social Sciences Key Research Base, Sichuan Provincial Department of Education, and member of the International Food Culture Research Association of the World Chinese Culinary Federation Along with the principal authors, two famous chefs checked the English translations. Fuchsia Dunlop - of Land of Plenty fame Professor Shirley Cheng - of Hyde Park New York's Culinary Institute of America Fuchsia Dunlop was actually the first (and to my knowledge, only) Western graduate from the school that produced the book. Recipes Here are screenshots of the table of contents. It has some recipes I'm a big fan of. ISBN ISBN 10: 7536469640 ISBN 13: 9787536469648 As far as I can tell, the first and second edition have the same ISBN #'s. I'm no librarian, so if anyone knows more about how ISBN #'s relate to re-releases and editions, feel free to chime in. Publisher Sichuan Science and Technology Press 四川科学技术出版社 Cover Okay... so this book has a lot of covers. The common cover A red cover A white cover A white version of the common cover An ornate and shiny cover There may or may not be a "Box set." At first, I thought this was a difference in book editions, but that doesn't seem to be the case. As far as covers go, I'm at a loss. If anybody has more info, I'm all ears. Buying the book Alright, so I've hunted down many sites that used to sell it and a few who still have it in stock. Most of them are priced exorbitantly. AbeBooks.com ($160 + $15 shipping) Ebay.com - used ($140 + $4 shipping) PurpleCulture.net ($50 + $22 shipping) Amazon.com ($300 + $5 shipping + $19 tax) A few other sites in Chinese I bought a copy off of PurpleCuture.net on April 14th. When I purchased Sichuan Cuisine, it said there was only one copy left. That seems to be a lie to create false urgency for the buyer. My order never updated past processing, but after emailing them, I was given a tracking code. It has since landed in America and is in customs. I'll try to update this thread when (if) it is delivered. Closing thoughts This book is probably not worth all the effort that I've put into finding it. But what is worth effort, is preserving knowledge. It turns my gut to think that this book will never be accessible to chefs that have a passion for learning real Sichuan food. As we get inundated with awful recipes from Simple and quick blogs, it becomes vital to keep these authentic sources available. As the internet chugs along, more and more recipes like these will be lost. You'd expect the internet to keep information alive, but in many ways, it does the opposite. In societies search for quick and easy recipes, a type of evolutionary pressure is forming. It's a pressure that mutates recipes to simpler and simpler versions of themselves. They warp and change under consumer pressure till they're a bastardized copy of the original that anyone can cook in 15 minutes. The worse part is that these new, worse recipes wear the same name as the original recipe. Before long, it becomes harder to find the original recipe than the new one. In this sense, the internet hides information.

-

Hey everyone. So im looking for the most affordable chocolate shaking table that actually works.. does anyone have experience with the ones from AliBaba or china in general? i bought a $100 dental table from amazon but i guess its not the right hrtz cause it kinda works, but not well enough. im looking in the $500 range or under.. any advice? Thanks

.thumb.jpg.f7b55ed2461d79f014af04dc3a669f43.jpg)

.thumb.jpg.74d9f933df2b740eec683b161224a07e.jpg)