Search the Community

Showing results for tags 'Chinese'.

-

I have just returned home after four days (three nights) in Guilin. This was a business trip, so no exotic tales this time. Just food. Anyway, despite its reputation, Guilin is actually a rather dull city for the most part - anything interesting lies outside the city in the surrounding countryside. I was staying in the far east of the city away from the rip-off tourist hotels and restaurants and spent my time with local people eating in normal restaurants. I arrived in Wednesday just in time for lunch. LUNCH WEDNESDAY We started with the obligatory oil tea. Oil Tea Omelette with Chinese Chives Stir-fried Mixed Vegetables Sour Beef with Pickled Chillies Cakes* Morning Glory / Water Spinach** * I asked what the cakes were but they got rather coy when it came to details. It seems these are unique to this restaurant. ** The Chinese name is 空心菜 kōng xīn cài, which literally means 'empty heart vegetable', describing the hollow stems.

-

Last week, Liuzhou government invited a number of diplomats from Laos, Malaysia, Indonesia, Myanmar/Burma, Poland, and Germany to visit the city and prefecture. They also invited me along as an additional interpreter. We spent Tuesday, Wednesday and Thursday introducing the diplomats to the culture of the local ethnic groups and especially to their food culture. First off, we headed two hours north into the mountains of Rongshui Miao Autonomous County. The Miao people (苗族 miáo zú), who include the the Hmong, live in the mid-levels of mountains and are predominantly subsistence farmers. Our first port of call was the county town, also Rongshui (融水 róng shuǐ, literal meaning: Melt Water) where we were to have lunch. But before lunch we had to go meet some people and see their local crafts. These are people I know well from my frequent work trips to the area, but for the diplomats, it was all new. So, I had to wait for lunch, and I see no reason why you shouldn't either. Here are some of the people I live and work with. This lovely young woman is wearing the traditional costume of an unmarried girl. Many young women, including her, wear this every day, but most only on festive occasions. Her hat is made from silver (and is very heavy). Here is a closer look. Married women dispense with those gladrags and go for this look: As you can see she is weaving bamboo into a lantern cover. The men tend to go for this look, although I'm not sure that the Bluetooth earpiece for his cellphone is strictly traditional. The children don't get spared either This little girl is posing with the Malaysian Consul-General. After meeting these people we went on to visit a 芦笙 (lú shēng) workshop. The lusheng is a reed wind instrument and an important element in the Miao, Dong and Yao peoples' cultures. Then at last we headed to the restaurant, but as is their custom, in homes and restaurants, guests are barred from entering until they go through the ritual of the welcoming cup of home-brewed rice wine. The consular staff from Myanmar/Burma and Malaysia "unlock" the door. Then you have the ritual hand washing part. Having attended to your personal hygiene, but before entering the dining room, there is one more ritual to go through. You arrive here and sit around this fire and wok full of some mysterious liquid on the boil. On a nearby table is this Puffed rice, soy beans, peanuts and scallion. These are ladled into bowls. with a little salt, and then drowned in the "tea" brewing in the wok. This is 油茶 (yóu chá) or Oil Tea. The tea is made from Tea Seed Oil which is made from the seeds of the camellia bush. This dish is used as a welcoming offering to guests in homes and restaurants. Proper etiquette suggests that three cups is a minimum, but they will keep refilling your cup until you stop drinking. First time I had it I really didn't like it, but I persevered and now look forward to it. L-R: Director of the Foreign Affairs Dept of Liuzhou government, consuls-general of Malaysia, Myanmar, Laos. Having partaken of the oil tea, finally we are allowed to enter the dining room, where two tables have been laid out for our use. Let the eating, finally, begin. In no particular order: Steamed corn, taro and sweet potato Bamboo Shoots Duck Banana leaf stuffed with sticky rice and mixed vegetables and steamed. Egg pancake with unidentified greenery Stir fried pork and beans Stir fried Chinese banana (Ensete lasiocarpum) Pig Ears This may not look like much, but was the star of the trip. Rice paddy fish, deep fried in camellia tree seed oil with wild mountain herbs. We ate this at every meal, cooked with slight variations, but never tired of it. Stir fried Greens Our meal was accompanied by the wait staff singing to us and serving home-made rice wine (sweetish and made from the local sticky rice). Everything we ate was grown or reared within half a kilometre of the restaurant and was all free-range, organic. And utterly delicious. Roll on dinner time. On the trip I was designated the unofficial official photographer and ended up taking 1227 photographs. I just got back last night and was busy today, so I will try to post the rest of the first day (and dinner) as soon as I can.

-

Last night i had an interesting experience...i shopped at my first real asian market. This was no joke. My only other interaction with an asian market had been at a slightly dingy market with a limited selection of asian produce. Even before entering i knew this was going to be special. Outside durian fruits and Pommelo were stacked high. Inside there was a case of beautiful roast duck next to a steamer full of Bao of all types. Huge and brightly lit aisles of fresh produce. Jack fruits, chinese broccoli, bitter asian melon, tubs of fresh seaweed. An amazing fish monger with rows of whole gleaming fish. Shark, grouper, snapper, skate, head on prawns. Below the iced counter top there were six or eight tanks of live fish and in buckets in front of the tanks were eels, turtle, frogs and blue crab. Seemingly endless choices of soy, ramen, condiments and rice. Then came the fear that in this great market with endless possibilities I had absolutely no idea what to get. It wasn't a planned trip and i didnt have as long as i would have liked to look around but i still felt guilty that i only left with a handful of snacks and items i had wanted to try. Given that this is a decent trek from home, how should i approach this next time? Im an asian food newbie when it comes to cooking but with a resource like that not too far away i would love to do some more asian cooking at home. I would like to stock up on some pantry staples but with so many choices i unsure of what to get and what was better quality. I think next time i want to go with 1-3 recipes to shop for, then on top of that a list of pantry ingredients to stock up on. Help me come up with a plan! thanks Brendan

-

I just bought these greens from the neighborhood Asian grocery. Had them once in China as a salad, and they tasted exceptional - a bit peppery like arugula, yet much more subtle and fresh, with hints of lemon. Store lady (non-Chinese) could not name them for me other than "Chinese greens". Any help identifying them is greatly appreciated

-

EGullet seafood specialists! One of the great, underused resources of Shanghai is the Tongchuan Wholesale Fish Market. It's a twenty minute cab ride north of town. It is more wholesale than retail, but there are plenty of average people out buying their seafood from a hundred or more different stalls. . Prices are cheap, selection is fantastic, and the best part is the restaurant street adjacent to the market, where you can take your purchases and have them cook them for you - they'll give you your suggestions for the cooking of each different fish, shellfish, or 'other'. Or you can bring your own butter, like we did on our last trip, ask them to melt it, and devour crabs and beer until you can't move. We try to do it monthly, and this time I brought my camera to help answer all of my "what the. . . " questions. I'm posting these photos in the hopes that our resident specialists can identify alot of these fish and "others" that I'm not familiar with. I'd really appreciate it if you can provide the english and/or mandarin chinese name, also, in pinyin or hanzi. The fish in the photos are numbered for reference, and there are also a couple of shots of the market in action. . Good luck!

-

I guess I do about half my food shopping in my local farmers' market and the other half in supermarkets. Today, I went to my favourite supermarket. They have lovely, very fresh vegetables, great fish and well... there isn't much they don't have. Here are a few pictures, beginning with the vegetable section:

-

A few days ago, I was given a lovely gift. A big jar of preserved lemons. I know Moroccan preserved lemons, but had never met Chinese ones. In fact, apart from in the south, in many parts of China it isn't that easy to find lemons, at all. These are apparently a speciality of the southern Zhuang minority of Wuming County near Nanning. The Zhuang people are the largest ethnic minority in China and most live in Guangxi. These preserved lemons feature in their diet and are usually eaten with congee (rice porridge). Lemon Duck is a local speciality and they are also served with fish. They can be served as a relish, too. They are related to the Vietnamese Chanh muối. I'm told that these particular lemons have been soaking in salt and lemon juice for eleven years! So, of course, you want to know what they taste like. Incredibly lemony. Concentrated lemonness. Sour, but not unpleasantly so. Also a sort of smoky flavour. The following was provided by my dear friend 马芬洲 (Ma Fen Zhou) who is herself Zhuang. It is posted with her permission. How to Make Zhuang Preserved Lemons By 马芬洲 Zhuang preserved lemons is a kind of common food for the southern Zhuang ethnic minority who live around Nanning Prefecture of Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region in China. The Zhuang people like to make it as a relish for eating with congee or congee with corn powder. This relish is a mixture of chopped preserved lemons, red chilli and garlic or ginger slice in soy sauce and peanut oil or sesame oil. Sometimes the Zhuang people use preserved lemons as an ingredient in cooking. The most famous Zhuang food in Guangxi is Lemon Duck, which is a common home cooked dish in Wuming County, which belongs to Nanning Prefecture. The following steps show you how to make Zhuang preserved lemons. Step 1 Shopping Buy some green lemons. Step 2 Cleaning Wash green lemons. Step 3 Sunning Leave green lemons under the sunshine till it gets dry. Step 4 Salting If you salt 5kg green lemons, mix 0.25kg salt with green lemons. Keep the salted green lemons in a transparent jar. The jar must be well sealed. Leave the jar under the sunshine till the salted green lemons turn yellow. For example, leave it on the balcony. Maybe it will take months to wait for those salted green lemons to turn yellow. Later, get the jar of salted yellow lemons back. Unseal the jar. Then cover 1kg salt over the salted yellow lemons. Seal well the jar again. Step 5 Preserving Keep the sealed jar of salted yellow lemons at least 3 years. And the colour of salted yellow lemons will turn brown day by day. It can be dark brown later. The longer you keep preserved lemons, the better taste it is. If you eat it earlier than 2 years, it will taste bitter. After 3 years, it can be unsealed. Please use clean chopsticks to pick it. Don’t use oily chopsticks, or the oil will make preserved lemons go bad. Remember to seal the jar well after picking preserved lemons every time.

-

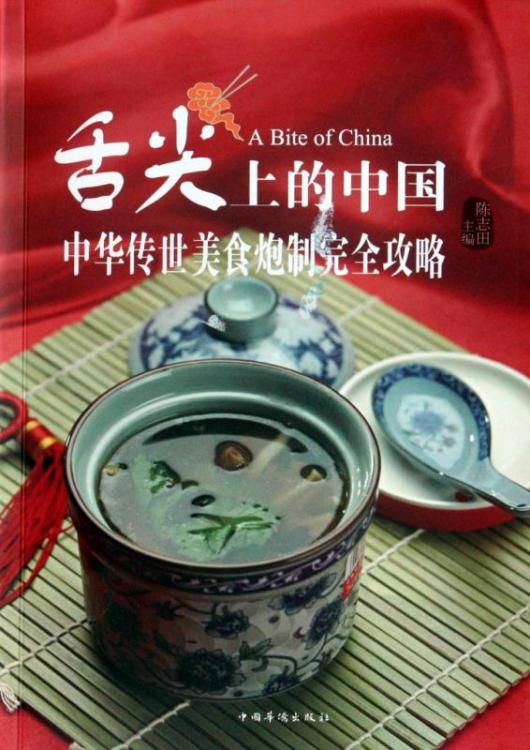

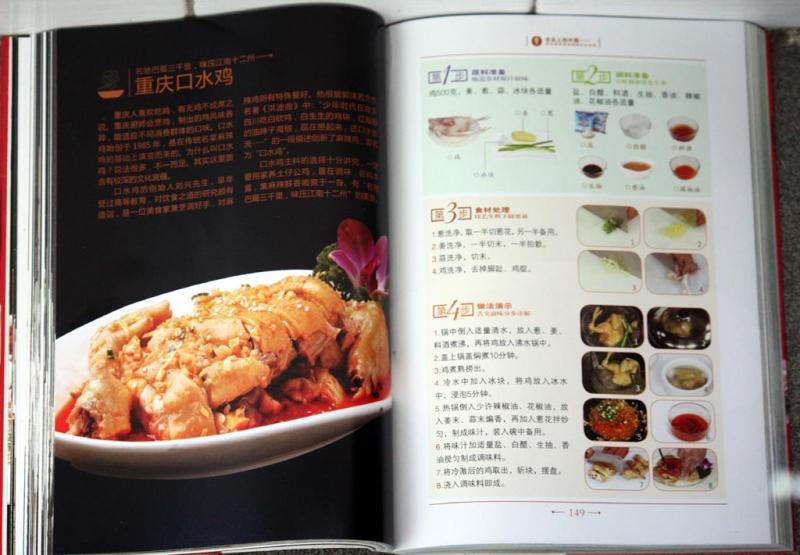

A few weeks ago I bought a copy of this cookbook which is a best-selling spin off from the highly successful television series by China Central Television - A Bite of China as discussed on this thread. . The book was published in August 2013 and is by Chen Zhitian (陈志田 - chén zhì tián). It is only available in Chinese (so far). There are a number of books related to the television series but this is the only one which seems to be legitimate. It certainly has the high production standards of the television show. Beautifully photographed and with (relatively) clear details in the recipes. Here is a sample page. Unlike in most western cookbooks, recipes are not listed by main ingredient. They are set out in six vaguely defined chapters. So, if you are looking for a duck dish, for example, you'll have to go through the whole contents list. I've never seen an index in any Chinese book on any subject. In order to demonstrate the breadth of recipes in the book and perhaps to be of interest to forum members who want to know what is in a popular Chinese recipe book, I have sort of translated the contents list - 187 recipes. This is always problematic. Very often Chinese dishes are very cryptically named. This list contains some literal translations. For some dishes I have totally ignored the given name and given a brief description instead. Any Chinese in the list refers to place names. Some dishes I have left with literal translations of their cryptic names, just for amusement value. I am not happy with some of the "translations" and will work on improving them. I am also certain there are errors in there, too. Back in 2008, the Chinese government issued a list of official dish translations for the Beijing Olympics. It is full of weird translations and total errors, too. Interestingly, few of the dishes in the book are on that list. Anyway, for what it is worth, the book's content list is here (Word document) or here (PDF file). If anyone is interested in more information on a dish, please ask. For copyright reasons, I can't reproduce the dishes here exactly, but can certainly describe them. Another problem is that many Chinese recipes are vague in the extreme. I'm not one to slavishly follow instructions, but saying "enough meat" in a recipe is not very helpful. This book gives details (by weight) for the main ingredients, but goes vague on most condiments. For example, the first dish (Dezhou Braised Chicken), calls for precisely 1500g of chicken, 50g dried mushroom, 20g sliced ginger and 10g of scallion. It then lists cassia bark, caoguo, unspecified herbs, Chinese cardamom, fennel seed, star anise, salt, sodium bicarbonate and cooking wine without suggesting any quantities. It then goes back to ask for 35g of maltose syrup, a soupçon of cloves, and "the correct quantity" of soy sauce. Cooking instructions can be equally vague. "Cook until cooked". A Bite of China - 舌尖上的中国- ISBN 978-7-5113-3940-9

-

OK, I'm getting a bit jealous about the amazing sense of community/identity the Toysan guys have. The rest of us, Overseas Chinese, where are you now, and where are you from? Starting from ngo.... I'm a 2nd generation chinese; My mom was born in Singapore, her mom's from Hong Kong. Cantonese. My dad was born in Malaysia, his family's from China. Hakka. Let's get this thread rolling (preferably in the direction of Food, or we'll get axed).

-

Proud of who we are and what we eat. A lot of younger participants of this forum may not realize it, but North American "Chinese" food served to the "lo fan" was largely created by us Toysanese...chop suey, sweet and sour ribs, garlic spare ribs, chicken balls, etc. But more than that, the style of "real" (I don't mean the newfangled fusion, spicey Szechuan, etc.) Chinese food served to the "lo wah kieu" during the abominable Exclusion days still can be called the mainstay of much of the Chinese restaurant industry in North America. I have to assume that I am the oldest Toysanese here, at least one who can still remember some of the aspects of village life in old pre-revolution China and as such, I would like to see this thread roll and I would be more than pleased to answer some of the questions (about whatever)you may have. And if I can't answer specifics about food, we can call on Dejah who is an accomplished chef and her Mother, her brain a precious repository of village recipes and culture. (Btw, Dejah is much, much, much younger than I) If your parents or grandparents came to "Gam Shan" before the mid 60s, chances are they are/were Toysanese, or just simply ask them.

-

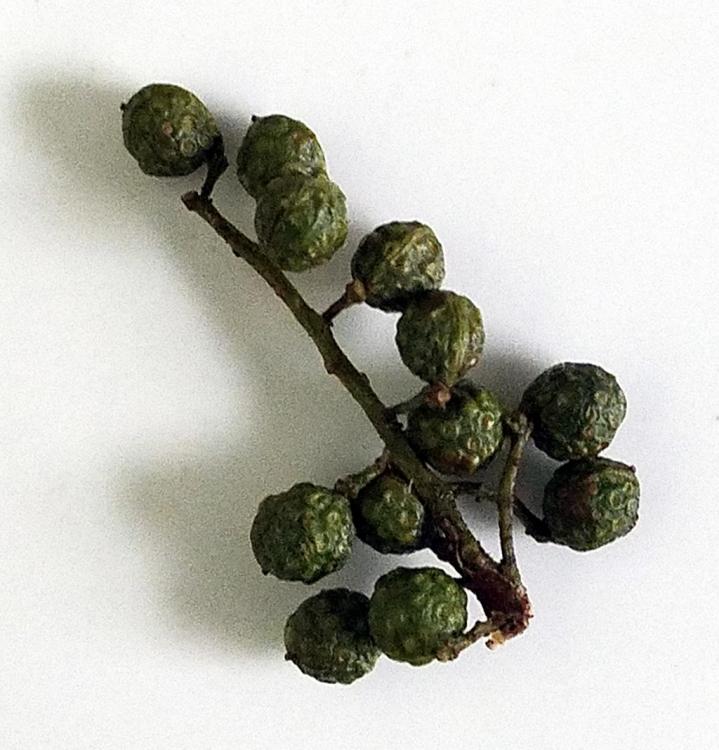

Your wish is my command! Sometimes! A lot of what I say here, I will have already said in scattered topics across the forums, but I guess it's useful to bring it all into one place. First, I want to say that China uses literally thousands of herbs. But not in their food. Most herbs are used medicinally in Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), often in their dried form. Some of the more common are sold in supermarkets, but more often in pharmacies or small specialist stores. I also often see people on the streets with baskets of unidentified greenery for sale - but not for dinner. The same applies to spices, although more spices are used in a culinary setting than are herbs. I’ll start with Sichuan peppercorns as these are what prompted @Tropicalsenior to suggest the topic. 1. Sichuan Peppercorns Sichuan peppercorns are neither pepper nor, thank the heavens, c@rn! Nor are they necessarily from Sichuan. They are actually the seed husks of one of a number of small trees in the genus Zanthoxylum and are related to the citrus family. The ‘Sichuan’ name in English comes from their copious use in Sichuan cuisine, but not necessarily where they are grown. Known in Chinese as 花椒 (huājiāo), literally ‘flower pepper’’, they are also known as ‘prickly ash’ and, less often, as ‘rattan pepper’. The most common variety used in China is 红花椒 (hóng huā jiāo) or red Sichuan peppercorn, but often these are from provinces other than Sichuan, especially Gansu, Sichuan’s northern neighbour. They are sold all over China and, ground, are a key ingredient in “five-spice powder” mixes. They are essential in many Sichuan dishes where they contribute their numbing effect to Sichuan’s 麻辣 (má là), so-called ‘hot and numbing’ flavour. Actually the Chinese is ‘numbing and hot’. I’ve no idea why the order is reversed in translation, but it happens a lot – ‘hot and sour’ is actually ‘sour and hot’ in Chinese! The peppercorns are essential in dishes such as 麻婆豆腐 (má pó dòu fǔ) mapo tofu, 宫保鸡丁 (gōng bǎo jī dīng) Kung-po chicken, etc. They are also used in other Chinese regional cuisines, such as Hunan and Guizhou cuisines. Red Sichuan peppercorns can come from a number of Zanthoxylum varieties including Zanthoxylum simulans, Zanthoxylum bungeanum, Zanthoxylum schinifolium, etc. Red Sichuan Peppercorns Another, less common, variety is 青花椒 (qīng huā jiāo) green Sichuan peppercorn, Zanthoxylum armatum. These are also known as 藤椒 (téng jiāo). This grows all over Asia, from Pakistan to Japan and down to the countries of SE Asia. This variety is significantly more floral in taste and, at its freshest, smells strongly of lime peel. These are often used with fish, rabbit, frog etc. Unlike red peppercorns (usually), the green variety are often used in their un-dried state, but not often outside Sichuan. Green Sichuan Peppercorns Fresh Green Sichuan Peppercorns I strongly recommend NOT buying Sichuan peppercorns in supermarkets outside China. They lose their scent, flavour and numbing quality very rapidly. There are much better examples available on sale online. I have heard good things about The Mala Market in the USA, for example. I buy mine in small 30 gram / 1oz bags from a high turnover vendor. And that might last me a week. It’s better for me to restock regularly than to use stale peppercorns. Both red and green peppercorns are used in the preparation of flavouring oils, often labelled in English as 'Prickly Ash Oil'. 花椒油 (huā jiāo yóu) or 藤椒油 (téng jiāo yóu). The tree's leaves are also used in some dishes in Sichuan, but I've never seen them out of the provinces where they grow. A note on my use of ‘Sichuan’ rather than ‘Szechuan’. If you ever find yourself in Sichuan, don’t refer to the place as ‘Szechuan’. No one will have any idea what you mean! ‘Szechuan’ is the almost prehistoric transliteration of 四川, using the long discredited Wade-Giles romanization system. Thomas Wade was a British diplomat who spoke fluent Mandarin and Cantonese. After retiring as a diplomat, he was elected to the post of professor of Chinese at Cambridge University, becoming the first to hold that post. He had, however, no training in theoretical linguistics. Herbert Giles was his replacement. He (also a diplomat rather than an academic) completed a romanization system begun by Wade. This became popular in the late 19th century, mainly, I suggest, because there was no other! Unfortunately, both seem to have been a little hard of hearing. I wish I had a dollar for every time I’ve been asked why the Chinese changed the name of their capital from Peking to Beijing. In fact, the name didn’t change at all. It had always been pronounced with /b/ rather than /p/ and /ʤ/ rather than /k/. The only thing which changed was the writing system. In 1958, China adopted Pinyin as the standard romanization, not to help dumb foreigners like me, but to help lower China’s historically high illiteracy rate. It worked very well indeed, Today, it is used in primary schools and in some shop or road signs etc., although street signs seldom, if ever, include the necessary tone markers without which it isn't very helpful. A local shopping mall. The correct pinyin (with tone markers) is 'dōng dū bǎi huò'. But pinyin's main use today is as the most popular input system for writing Chinese characters on computers and cell-phones. I use it in this way every day, as do most people. It is simpler and more accurate than older romanizations. I learned it in one afternoon. I doubt anyone could have done that with Wade-Giles. Pinyin has been recognised for over 30 years as the official romanization by the International Standards Organization (ISO), the United Nations and, believe it or not, The United States of America, along with many others. Despite this recognition, old romanizations linger on, especially in America. Very few people in China know any other than pinyin. 四川 is 'sì chuān' in pinyin.

-

Anyone ever tried this dish? http://www.flickr.com/photos/jin_lee/426541484/ http://www.flickr.com/photos/d_flat/112708015/ It's supposed to be a chicken and potato 'stew' (ish) and you add wide noodles to it afterwards to soak up the sauce. I've never tried it myeslf but it looks absolutely delish! A specialty from Xinjiang (apparently). If anyone is able to offer their experience/taste sensation with this dish or even better, a recipe, I'd be really grateful!

-

Does anyone have a recipe for Zha Jiang 炸酱, the sauce used with noodles to make Zha Jiang Mien 炸酱面? Please!

-

Yesterday, an old friend sent me a picture of her family dinner, which she prepared. She was never much of a cook, so I was a bit surprised. It's the first I've seen her cook in 25 years. Here is the spread. I immediately zoomed in on one dish - the okra. For the first 20-odd years I lived in China, I never saw okra - no one knew what it was. I managed to find its Chinese name ( 秋葵 - qiū kuí) in a scientific dictionary, but that didn't help. I just got the same blank looks. Then about 3 years ago, it started to creep into a few supermarkets. At first, they stocked the biggest pods they could find - stringy and inedible - but they worked it out eventually. Now okra is everywhere. I cook okra often, but have never seen it served in China before (had it down the road in Vietnam, though) and there are zero recipes in any of my Chinese language cookbooks. So, I did the sensible thing and asked my friend how she prepared it. Here is her method. 1. First bring a pan of water to the boil. Add the washed okra and boil for two minutes. Drain. 2. Top and tail the pods. Her technique for that is interesting. 3. Finely mince garlic, ginger, red chilli and green onion in equal quantities. Heat oil and pour over the prepared garlic mix. Add a little soy sauce. 4. Place garlic mix over the okra and serve. When I heard step one, I thought she was merely blanching the vegetable, but she assures me that is all the cooking it gets or needs, but she did say she doesn't like it too soft. Also, I should have mentioned that she is from Hunan province so the red chilli is inevitable. Anyway, I plan to make this tomorrow. I'm not convinced, but we'll see. to be continued

-

I see this vegetable often, but I'm never sure what it is. I asked a waitress a few nights ago, while I was eating a dish of "Enchanted Pork," littered with this vegetable. It looks like it's been cut from a stalk. I typically see it cut into little, flat green rhombuses. It could very well be a regular old leek, but I can't tell. Any ideas?

-

Note: This follows on from the Munching with the Miao topic. The three-hour journey north from Miao territory ended up taking four, as the driver missed a turning and we had to drive on to the next exit and go back. But our hosts waited for us at the expressway exit and led us up a winding road to our destination - Buyang 10,000 mu tea plantation (布央万亩茶园 bù yāng wàn mǔ chá yuán) The 'mu' is a Chinese measurement of area equal to 0.07 of a hectare, but the 10,000 figure is just another Chinese way of saying "very large". We were in Sanjiang Dong Autonomous County, where 57% of the inhabitants are Dong. The Dong people (also known as the Kam) are noted for their tea, love of glutinous rice and their carpentry and architecture. And their hospitality. They tend to live at the foot of mountains, unlike the Miao who live in the mid-levels. By the time we arrived, it was lunch time, but first we had to have a sip of the local tea. This lady did the preparation duty. This was what we call black tea, but the Chinese more sensibly call 'red tea'. There is something special about drinking tea when you can see the bush it grew on just outside the window! Then into lunch: Chicken Soup The ubiquitous Egg and Tomato Dried fish with soy beans and chilli peppers. Delicious. Stir fried lotus root Daikon Radish Rice Paddy Fish Deep Fried in Camellia Oil - wonderful with a smoky flavour, but they are not smoked. Out of Focus Corn and mixed vegetable Fried Beans Steamed Pumpkin Chicken Beef with Bitter Melon Glutinous (Sticky) Rice Oranges The juiciest pomelo ever. The area is known for the quality of its pomelos. After lunch we headed out to explore the tea plantation. Interspersed with the tea plants are these camellia trees, the seeds of which are used to make the Dong people's preferred cooking oil. As we climbed the terraces we could hear singing and then came across this group of women. They are the tea pickers. It isn't tea picking time, but they came out in their traditional costumes to welcome us with their call and response music. They do often sing when picking. They were clearly enjoying themselves. And here they are: After our serenade we headed off again, this time to the east and the most memorable meal of the trip. Coming soon.

-

A famous saying in China goes: "A perfect life is possible if one is born in Suzhou (home of the most beautiful women), dressed in Hangzhou (finest silks), dies in Luzhou (best willow wood for coffins), but eats in Guangzhou (Canton, capital city of Guangdong province and home of classical Cantonese cuisine)." Cantonese food was considered the most delicious by the Chinese themselves. Non-Chinese diners in the U.S., familiar with Cantonese-style restaurants, might disagree with this assertion. Typical Cantonese food in the U.S. has been altered, sometimes beyond recognition, by circumstances; it's Cantonese in concept but not execution. Chinese workers from the districts of Toi San And Sun Tak (near Canton) were among the first Chinese immigrants to the West in the 19th century. U.S. immigration policy at that time seriously limited the number of Chinese women allowed in -- the idea was that when the railroads were built, the Chinese would go home. The laborers cooked for themselves, as best they could, and when the railroads were built, they settled in American cities and some opened restaurants. They cooked the food they knew -- village-style, home cooking -- and were further limited by climate, available ingredients, and distance from tradition, as well as their practical need to please Western palates. And so we got yucky Chinese food -- cloying sweet and sour pork with canned pineapple, awful chow mein and chop suey, eggy sticky shrimp with lobster sauce, tasteless brown sauces thickened with cornstarch, msg headaches. The 1970s was a golden age for Cantonese cuisine in the U.S. because of changes in immigration policies that allowed many more Chinese from Hong Kong into the U.S. Huge dim sum restaurants opened, and many chefs from Hong Kong arrived. I was lucky to be studying Chinese in New York at the time, and got invited to many Chinese banquets, as well as wonderful family restaurant meals where I ate food much closer to the classic Cantonese repertoire. My best friend's mother often took me on day-long eating and food shopping expeditions in Chinatown. At that time, the meat, seafood and produce were exceptionally fresh, because people demanded it. I was amazed at how so many of the Cantonese people I met were obsessed with food (on an eGullet level). I watched people order what they wanted without even consulting the Chinese menu. They simply wrote down the dishes they wanted on a piece of paper and handed it to the waiter. Everyone seemed to know the best places to go to as soon as they appeared. Guangdong province is in the south, with a long coastline and several large rivers down which produce can be shipped from the interior. The climate is semi-tropical; two rice crops are harvested a year. More than in many areas of China, there was usually enough food, and a great variety of ingredients. These factors shaped a delicious cuisine whose underlying philosophy is absolute freshness and a concurrent desire to preserve the essential nature and sweet flavor of each ingredient. Various techniques are employed to achieve this. One method is to cook food for short periods of time, or to use very mild forms of cooking. Food is poached in boiling water and then removed from the fire to finish cooking in the slowly cooling liquid. White cut chicken is an example of this method, as is soy sauce chicken (both are the chickens you see hanging in restaurant windows). For these dishes to work, the chicken has to be absolutely fresh. (The Cantonese prefer chicken slightly undercooked to Western tastes, leaving a little blood near the bone.) The delicate flavor of the white cut chicken is set off by a dipping sauce of soy sauce, chicken broth, ginger, scallions and sesame oil. Shrimp are also cooked with this method -- boiling water is poured over very fresh shrimp in their shells, left to stand for a few minutes and then drained. More boiling water is poured over, drained again, and the shrimp are then eaten with a dip of tangerine juice, minced scallion, soy sauce and shredded ginger root in vinegar. Brief steaming is another method that preserves the fresh, sweet taste. Whole fish such as sea bass, bream or carp are steamed until just cooked and served with a thin sauce of soy, chicken stock, ginger, scallions and wine. A little oil can be heated just before serving and poured over the fish. Greens of all kinds are blanched to preserve the natural flavor. The Cantonese even have a dish similar to sashimi -- a live carp is pulled from the water, knocked on the head and stunned, split, gutted, scaled and filleted and eaten immediately with a dipping sauce of ginger, soy, boiled peanut oil, scallion and white pepper. Stir-frying also is designed to retain the pure flavors of ingredients. Only a small amount of oil is used and the food is quickly whisked through the oil under very high heat in a manner described as "flame and air." The savory quality of Cantonese food is often achieved by combining seafood flavors with meat. Oyster sauce, shrimp sauce and shrimp paste are widely used (similar to the use of fermented fish in Southeast Asian cooking). Shrimp shells and heads are boiled in meat or chicken stock to add depth of flavor to soups and sauces. Sometimes meat is added to seafood dishes to enhance the savoriness. An example is the classic Lobster Cantonese, in which minced or shredded pork is stir-fried with onions, garlic, ginger and soaked, mashed salted black beans together with lobster (or crab). Chicken stock and wine are added at the last minute, creating a little explosion in the wok, and then again in your mouth. The Cantonese specialize in crispy foods, where the skin of pork and poultry is crisp and crackling, such as Crispy Skin Roast Pork (belly pork). Here the crunchiness of the skin is set off by the plain white rice served with it. Chicken is prepared as Crispy Deep-Fried Steamed Stuffed Chicken or Twice-Marinated Crispy Skin Splash-Fried Chicken. Pigeon is also deep-fried. A Cantonese specialty comparable to Peking Duck is Suckling Pig, served with the deep brown, crisp skin (that's brushed with a marinade before roasting) peeled off, cut into squares and served, with the tender meat, with small steamed Lotus Leaf Buns, scallions and hoisin sauce. Cantonese- (or Hong Kong) style Chow Mein is cooked using more frying oil than in other regions. The noodles are pressed down into the pan to make them crisper, and then turned and fried on the other side, to create a sandwich of crisp outer noodles with tender noodles inside. Home cooking features slow-cooked dishes in earthenware casseroles, among them beef stew braised with daikon radish and star anise (the beef cut is similar to flanken), fish head in casserole, and red braised pork knuckle or belly. Congee is also a common snack food in Canton. For spiciness, fermented black beans and small amounts of chiles are used. Subtle scents and flavors are introduced by adding drops of sesame oil or by wrapping food in lotus or bamboo leaves, such as lotus leaf sticky rice with duck, roast pork, dried mushrooms and chestnuts, and aromatics. I've always been fascinated by the array of dried foods and preserved meats in Chinese stores -- pork sausage, duck liver sausage, bacon, dried fish maw (air bladder), dried scallops and squid and shrimp, all the different dried mushrooms, deep-fried and then dried squares of bean curd which are stuffed with savory meat or seafood minces and then steamed, and the salted preserved vegetables in earthenware jugs, and fermented bean curd (the latter often added to quickly wilted greens such as watercress). Textural foods, such as bird's nest, tree fungus, beche-de-mer, fish maw, and shark's fin, are Cantonese in origin, and are mostly found in banquet cooking. Great Assembly of Chicken, Abalone and Shark's Fin is an extravagant banquet dish, in which the shark's fins are cooked separately for over 7 hours and then gently cooked together with lean pork meat, pig's feet, ham, onions and a hen for another 4 hours. The pork, feet, ham, onion and chicken are then removed and put aside for other uses. A young chicken is then quartered, parboiled and left to simmer with the shark fins for another half hour. Abalone and soy sauce are briefly added. The chicken and abalone are cut into thin slices and arranged at the bottom of a deep, ceramic cooking dish. The liquid in the pot is strained and returned to simmer with the fins for another 30 minutes. The fin pieces are then arranged on top of the chicken and abalone. Some of the sauce, now thickened, is poured over to moisten and the pot is steamed for 5 minutes and then served. The shark fins are there primarily for their texture, but that's the point of the whole time-consuming process. My friend's mother used to make a medicinal soup using the double pot method of cooking. She put blanched squabs inside a pot with chicken stock, ginger, scallions, ginseng root, and rice wine. The pot was then covered and placed inside a bigger pot filled with water, which was then covered and cooked for a long time. And then there's dim sum, which epitomizes all of the savory deliciousness and love of eating found in Cantonese cooking and among Cantonese people.

-

I am having a dinner party on Sunday...for about 16 people. They requested dim sum as it is not readily available in our small city. So far, I have made beef meat balls, har gow, sui mai, curry chicken in puff pastry, chicken/lapchung/mushroom steamed buns, sticky rice in lotus leaf. I will also have ribs in black bean garlic sauce and a lomein with lots of vegetables. Questions: Can anyone suggest a good or complimentary order to serve up these items? What would be a good soup to serve with this? I know they would love hot 'n'sour or congee...but I feel these would be "too heavy". How about dessert? I was thinking of red bean/lotus nut soup and fresh fruit tray? Tea would be best? BTW, I am new to the forum, and I am having a blast reading all the posts! Thank you

-

Hello, I am not sure that this should be a separate thread but, as a complement to the thread “A pictorial guide to chinese ingredients”, here goes. I live in Paris and am exploring Chinese regional cuisines. To execute the different recipes (mostly in English), I have bought ingredients from specialty shops often by showing the Chinese characters for ingredients I cannot find. I wonder if you have the same problem of needing the Chinese equivalent for an ingredient. If so, perhaps the following list in English and Chinese would be useful. Since I am not Chinese, I probably have made some mistakes; if so, please correct them and I thank you ahead of time. Also, since there are surely many other ingredients which I have not yet used, please add them if you will. Have a good day ! I have made my list in alphabetical order: abalone, canned (鲍 鱼 ) alcohol, Chinese: Fenjiu or Fen Chieu (汾 酒 ) asian eggplants (茄 子) bamboo shoots (竹 笋 ) bean curd, fresh (豆 腐 ) black beans, salted/fermented (豆 豉 ) black bean sauce ( 豆 豉 酱 ) cabbage ….. white Beijing variety (aka Napa) (大 白 菜 ) ….. green Shanghai variety (aka bok choy) (上 海 白 菜 ) celery, Chinese ( 芹 菜 ) chili bean sauce ( 辣 豆 瓣 酱 ) chile bean paste ( 豆 瓣 酱 ) chili (hot peppers), dried ( 干 辣 椒 ) chili oil ( 辣 椒 油 ) chives, Chinese or garlic (韭 菜 ) cinnamon or cassia bark, Chinese ( 桂 皮 ) coriander leaves (aka Chinese parsley/cilantro) ( 芫 荽 or 香 菜 ) five-spice powder, Chinese ( 五 香 粉 ) ginger ..... fresh ginger .…. young ginger ( 子 姜 ) marinated ginger ( 腌 姜 ) ginseng ..... american ginseng ( 花 旗 参 ) ….. white panax ginseng ( 白 蔘 ) ….. red panax ginseng ( 红 蔘 ) ….. young ginseng (dangshen) ( 党 参 ) green algae in powder ( 绿 色 紫 菜 粉 ) hoisin sauce ( 海 鲜 酱 ) ….. sweet flour sauce ( 甜 面 酱 ) lily flowers (aka golden needles), dried ( 金 針 ) lotus leaves, dried ( 荷 叶 ) mushrooms ….. black mushrooms, dried ………. wood ear mushrooms ( 木 耳 ) ………. cloud ear mushrooms ( 云 耳 ) ………. snow ear mushrooms ( 雪 耳 ) ….. fragrant mushrooms (or shiitake) (香 菇 ) noodles ….. bean thread (or cellophane) noodles ( 粉 丝 ) ….. (fresh) egg noodles ( 鲜 蛋 面 ) ….. Shanghai noodles (or udon) ( 上 海 粗 面 ) oyster sauce ( 蚝 油 ) pandan leaves ( 斑 兰 叶 ) pickled mustard leaves ( 咸 菜 or 咸 酸 菜 ) ….. red-in-snow ( 雪 菜 or 雪 里 红 ) plum sauce ( 酸 梅 酱 ) rice ….. "long grain" white rice ….. glutinous rice ( 糯 米 ) ….. red rice ( 红 米 ) rice wine ( 米 酒 or 料 酒 ) rice wine from Shaoxing ( 紹 兴 酒 or 紹 兴 花 雕 酒 ) rice wine vinegar ….. white rice wine vinegar ( 白 米 醋 ) ….. black rice wine vinegar ( 香 醋 ) ….. black rice wine vinegar from Zhenjiang/Chinkiang ( 鎮 江 香 醋 ) sausage, Chinese ( 香 肠 or 腊 肠 ) scallions ( 葱 ) scallops, dried ( 瑶 柱 ) sesame oil ( 香油 or 麻油 ) sesame paste ( 芝 麻 酱 ) sesame seeds ….. white sesame seeds ( 白 芝 麻 ) ….. black sesame seeds ( 黑 芝 麻 ) shrimp chips ( 虾 饼 干 ) shrimp, dried ( 虾 米 ) Sichuan peppercorns ( 花 椒 ) Sichuan preserved vegetable ( 四 川 榨 菜 ) snow peas ( 雪 豆 or 荷 兰 豆 ) soy sauces ….. soy sauce (light or thin) ( 生 抽 ) ….. soy sauce (dark or thick) ( 老 抽 ) star anise (八 角 or 大 料 ) starch/flour ….. corn ( 太 白 粉 ) ….. potato ( 生 粉 ) ….. sweet potato ( 地 瓜 粉 ) sugar ….. brown sugar ….. rock sugar ( 冰 糖 ) taro root ( 芋 头 ) water chestnuts ( 荸 荠 ) ….. water chestnut powder ( 荸 荠 粉 or 马 蹄 粉 ) ….. jicama (fresh water chestnut substitute) (豆 薯 ) white radish, Chinese ( 白 萝 卜 ) wolfberries ( 枸 杞 子 ) yellow bean sauce ( 黄 豆 酱 )