-

Posts

1,025 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Store

Help Articles

Posts posted by albiston

-

-

Haven't had much time to dedicate myself to cooking lately, but just reading these regional cooking threads has made up for it. Great efforts form everyone! Too bad one cannot taste the lovely descriptions and pics.

So, while I haven't done any Ligurian cooking I did manage a little focaccia baking last week-end.

The base was classic focaccia dough (flour, water, salt and olive oil) made with a pre-fermented poolish-style starter and rise-retarded overnight in the fridge. With that I made two focaccie. First a classic one, topped only with extra olive oil (from Umbria, no Ligurian oil available around here) and a little salt (before baking, below),

It mysteriously disappeared before I could take a picture of the finished baked product

I also made a less traditional one with thyme, olive, onion and tomato topping.

-

I do from time to time.

You know, that guy called Alberto who started this whole madness of food and wine blogging events is... ehm, yours truly

.

. -

The last entry with the metamorphases looks particularly intriguing. If the flavors of that apple and raspberry dish are anywhere near half as good as the plated dessert they would be awesome indeed. Her concept is very interesting. I can't say that I have seen or heard of that before.

I can't say that either. Laura Fanella is a nice addition to the exciting (but small) new generation of excellent Italian pastry chefs, which I only see as a good thing given that sometimes the desserts one often finds in Italian restaurants can range from depressing to merely inoffensive. It remains to be seen if she'll continue to work in restaurant kitchens or decide to open a pastry shop, like some of her talented colleagues. One thing is sure, she captured the attention of those who met her: Paolo Marchi (the guy who organised IG) was so enthusiastic about her talk that in his Italian newsletter he dedicated a small article to her under the header "A star is born".

-

In a congress dedicated to the interplay of sweet and savory foods it is perhaps ironic that sweets came last (but not least), just as the classic restaurant service would have. Nonetheless, the afternoon session of the final day of Identità Golose offered a chance to hear some of the most interesting pastry chefs in Italy and Spain talking about their work and to have a peek at their creations.

The opening talk was given by Angelo Corvitto, Italian master ice-cream maker working in Spain since the mid 60s, now running Gelatiere in Torroella del Mongri where people can savour the full range of his ice flavors. He demonstrated his technique for cold maceration, making evident, if needed, that the certainties of yesterday's cooking methods (hot maceration in this case) are being refuted in the eye of today's scientific analysis.

While heat allows to shorten the infusion times of liquids, it also extracts bitter flavors and alters the taste of ingredients, which are on the contrary fully preserved if macerated for several days at 4-6°. This simple but revolutionary technique can be successfully applied to teas, aromatic herbs, spices and coffee to prepare ice-creams and sherbets, but also mousses and salty dishes, so much that in Spanish restaurants it has become the de rigeur thing: “ice cream needs restaurant to evolve, where strong flavors can be tried even with valued ingredients”, Corvitto stated.

To those who follow our Spanish forum El Celler de Can Roca in Girona is no stranger (discussion about the restaurant on our Spain forum here), as are the three Roca brothers, respectively chef, sommelier, and Jordi, the youngest, pastry-chef. Jordi has received a number of awards throughout the past few years, like Lo Mejor de la Gastronomia's 2003 prize as best Spanish pastry chef, and his perfume-inspired desserts have broken new grounds in modern pastry art.

The first dessert prepared by Jordi was an Havana cigar, similar at first sight to children chocolate cigarettes (above). He first insufflated some cigar smoke with a pipe through the cream, then shaped this like a cigar, chocolate coated it and laid it on a bed of sweet coal on a false ash-tray, to be served with a revisited mojito in an homage to Cuba. For his work on fragrances, Roca chooses fruity and spicy scents rather than floral ones, breaks them up into their basic aromas and assembles these again under in edible form, using different techniques to give each scent off in the right sequence; at the end, the customer receives a small cardboard soaked in the original perfume, to quickly compare the sensations felt. Hypnotic Poison by Christian Dior, for example, became a mixture of vanilla cream, rose jam, strawberry jelly, Tonka purée and caramelized petals. Roca finished his demo with an very technical dessert: an ethereal ball of pulled sugar (obtained with sugar, glucose, isomalt and citric acid), filled with smoke and served on a bed of ceps carpaccio and ceps ice-cream.

Jordi Butron from Espai Sucre (meaning sweet space) in Barcelona completed the Spanish section of the afternoon. Butron's is the first dessert's restaurant in the world: not a pastry shop, but a real restaurant serving testing menus of desserts (some discussion about it hereonthe Spain forum). His approach to dessert was gradual, involving experiences with Christophe Felder, Chef pâtissier of the Carillon hotel in Paris, Michel Bras and Pierre Gagnaire, plus Jean Luc Figueras in Barcelona. Butron's philosophy of dessert, even though equally sophisticated and involving, is against excessive experimentation and technological determination: “I do not like “show” desserts that you never know how to eat”, he declared, and again: “technique shall not be the end, as often happens, but the means to maximize taste.”

His demo began by considering the pear, a tiresome ingredient in pastry-making because it is watery and granular. After looking at the elective pairings for this fruit (fats and nuts), he chose three; butter, pine-nuts and cracklings to avoid obvious solutions. Butron then considered that sweetness wouldn’t be balanced without a digestive, balsamic and weighing up note, given in this case by aniseed and fennel. The following step was the choice of how to plate this conceptual description: the pear was served in a pie wholly made of its pulp, the scraps of pork fat in a pâte brisée, pine-seeds as ice-cream, the whole sprinkled with fennel and caraway sprouts.

In a time where chefs look at the methods and ideas used by pastry chefs, there are pastry chefs too that look at what line chefs are doing for inspiration: like Corrado Assenza (bio only in Italian unfortunately) from Caffè Sicilia in Noto (Sicily). Assenza's work in Noto started in 1985 when he took over Caffè Sicilia together with his future wife and his brother, leaving an academic career (he is a graduate in agricultural studies) which nonetheless left him with a particular attachment to honey as pastry ingredient. His work focuses on emotions and his terroir, as creations such as his oregano-infused cream ice with Bronte pistachios show: "People are increasingly careful about what they eat; we have turned back to being hunters, but this time we're hunting emotions. The emotion I want to transmit is the uniqueness of this Baroque country (i.e. Noto and surroundings) through the language of cooking."

His first dessert was devoted to ricotta, trying to recreate the feelings aroused by the breakfast his mother used to prepare when he was a child, mixing the cheese with cinnamon and sugar. A Sicilian ricotta pie was served with vanilla and Sichuan pepper lasagna boiled in water, salt and honey, stuffed with almond cream(to imitate Béchamel sauce) and with all the special jams of Caffè Sicilia as side dish. The second dish converted the classical orange and fennel salad Sicilian farm laborers are used to eat for lunch into a sweet (above): anchovies were pickled in honey, bread was replaced by a spicy pastry, the dried tomato became sweet as well as the grilled pepper. To further underline the Sicilian origin of the dishes Assenza used local thickeners such as carob flour and almond powder in his dishes.

A part of the history of Italian confectionery came on the stage with Iginio Massari, of Pasticceria Veneto in Brescia, representing those who work in pastry shops rather than restaurants. If Gualtiero Marchesi is the dean of Italian chefs, as Veronelli was that of Italian food journalists, then Massari earns a similar position in the Italian pastry scene. Sine opening his shop in 1971, Massari has made a name as a perfectionist with regards to both technique and ingredients as shown by his sweets and his books.

He showed the complex preparation of the “Bengodi” (land of plenty, but also a reference to Boccaccio) cake, the dessert of his dreams. It is made of a "fake amaretto" of coconut meringue, layered with mango cream, pineapple and rum ice-cream and mousse and coated with Italian meringue flavoured with vanilla and lemon. His speech, focused on classical techniques, was characterized by Massari's humor and jokes, such as that about dietetic dishes: “The sins of gluttony should be committed to the very end, without decreasing the richness of preparations. Dietetic sweets and meals are dietetic because I never succeed in finishing them. Because they taste bad."

The next guest on stage, Enrico Cerea of Da Vittorio in Busaporto near Bergamo,received the prize “Lombard excellence in cooking” from the hands of Viviana Beccalossi, vice-governor of the Lombard Region and councilor for agriculture. He devoted it to the memory of his recently deceased father Vittorio with heartfelt words. Enrico has taken up the leadership of the restaurant after the sad event although the whole Cerea family works together to make this one of the most unique dining destinations in Italy (plus running the Cavour pastry shop in Bergamo). I can say without fear of being corrected that da Vittorio is also a favourite of my co-host Robert Brown: you can read his reports (and more) here.

The chef brought on stage a touch of clever realism, showing the possibilities available to propose creative desserts in banqueting contexts, an professional opportunity few chefs can afford to dismiss today, especially in Italy. The first theme was Carnival, which in Italy means foremost fried foods. For this festivity Cerea created a cocoa bean caramelized fritter, stuffed with mandarin cream with torrone mousse and mandarin sherbet. Similarly, strudel was also proposed in a fried version and shaped as a Sicilian cannolo (above): filled with strudel mousse, it was laid on a bed of apples sautéed with pine nuts, cinnamon custard and cardamom ice-cream.

Late in the evening, the young Loretta Fanella took stage for the closing talk of Identità Golose's second edition. Loretta, who is 25 , is now pursuing her own career, after a long experience at Carlo Cracco of Cracco-Peck in Milan, and a season at el Bulli with Albert and Ferran Adrià.

On the stage she showed two original personal creations. The first dessert allowed to show the cold maceration technique: raw fruit is vacuum sealed with a liquid, where an osmosis is created which produces a metamorphosis of tastes. In this case the apple was "turned into" a raspberry (above), yet retaining its crunchy texture; a similar method can be used with pears and coffee, or to infuse a fruit with sugar or liquor syrups. The dessert was completed with a lavender mousse and lavender sticks covered with kappa jelly, to be sucked as lollipops. The final dish combining persimmon and liquorice was described as surprisingly appealing by the lucky few who got a taste.

This concludes the look at the 2006 edition of Identità Golose, but not this thread: there is plenty of room for discussion.

-

With a little guilty delay on my part, we get to the final day of Identità Golose, divided between a morning session dedicated to savory dishes and an afternoon one on desserts, this being the culminating session of the parallel event Dossier Dessert.

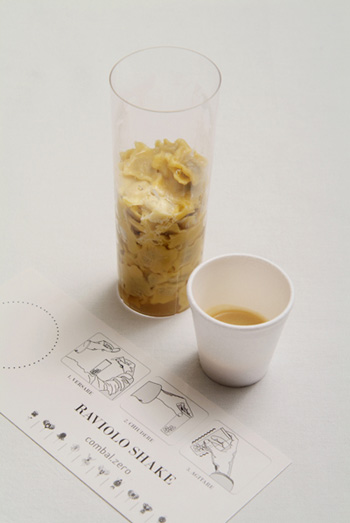

After so much virtual dough, the fevered Davide Scabin, of Combal.zero in Rivoli (Torino), proposed a take on the classical Piemontese ravioli –egg yolk and flour pasta dough, stuffed with meat– and dressed with a sauce made of butter and rosemary. The choice might seem somewhat puzzling coming from a chef with Scabin's reputation for creativity and "modern" cooking. At Combal.zero Scabin serves both a menu of revisited Piemontese classics and a highly creative one, yet he is mainly known (maybe unjustly so) for the latter. This menu is a combination of playful food-games and avant-garde methods, which have won him many fans and a few enemies.

His take on ravioli is both classic and technically modern, cunning (three types of butter, noisette , melted and iced mixed with a strict timing) and playful: shacked ravioli. The audience received a plastic glass full of hot mignon ravioli – each single raviolo weighing less than than one gram - to which they added the sauce contained in another small glass and shacked it all, as the cook would have done sauteeing. This allows to serve a perfect express dish during a banqueting context, a kind of service often loathed by chefs, but something Scabin is clearly interested to: “Today cooking is too much unbalanced towards over-intellectualism and competitiveness, but I’m not interested in being a phenomenon for 4 people. My challenge is to keep a high quality standard even with great numbers, going on exciting”, he stated.

Massimo Bottura followed Scabin on stage, fresh from the second Michelin’s star and the prize won in San Sebastian (during Lo Mejor de la Gastronomia) for the best extra virgin olive oil dish. Chef of La Francescana in Modena, Bottura's cooking is in constant evolution. In the past the influence of his experiences with the likes of Adrià, George Cogny and Alain Ducasse was quite clear in his dishes, yet his cooking now managed to evolve into a personal and mature style. While the avant-garde influences are undeniable, Bottura nonetheless manages to keep his culinary roots in clear view (for example wth his parmesan four ways entree) and is not afraid to serve "simple" and unadorned selected salumi as appetiser.

He led the public into the meanders of a cook’s mind, showing how a jumble of impressions can generate a great dish. Inspired by Jamaican jerked chicken he explained how he evolved his take on the popular bird. The final dish (above) is a composition of jerked breast meat, accompanied by a mango and papaya mayonnaise, a torchon of smoked chicken livers decorated by sous-vide crests and a Basmati rice cappuccino sauce made foamy using lecithin. The chicken was paired to "Caesar salad"... Emilia Romagna style, where, among other details, the lettuce of the classic recipe was substituted with the local misticanza, a mix of wild salads, herbs and flowers. “My cooking is evocative, it makes ideas concrete through products and techniques, on the basis of the emotions kept in our memory”, was Bottura's remark.

After Adrià, the Spanish culinary avant-garde came anew on stage with Dani Garcia, a very young chef from Marbella and the best cook of Spain in 2006 according to Lo mejor de la Gastronomia. Garcia has been on the radar of gourmets and critics alike since 2001, when he was awarded his first Michelin star, at only 25, for his work at Tragabuches in Ronda. Since his move to Calima, restaurant of the luxury Gran Meliá Don Pepe Hotel, the expectations and attention Garcia recieves have if anything grown.

His speech was focused on the use of liquid nitrogen as culinary "cooking" method. “Diffidence is still high – Dani declared – but nitrogen is commonly used at industrial level and we all breath it 14 times per minute”. To start there was a sort of impalpable Andalusian olive oil granita, which many in the audience could try. One of the comments: “It has an unusual consistency, because it doesn’t go from solid to liquid state like an ice-cream, but makes flavors burst in the mouth. Many people think that cold spoils tastes and flavors, but it isn’t always so”. Then, it was the turn of “pop corn” (above) obtained siphoning a mix of tomato water and olive oil into liquid nitrogen. In this case too, after tasting comments were keen. His intervention ended up showing two cold soups: a reviewed Andalusian gazpacho, with cherries and cheese mousse and a new version of ajo blanco.

Mauro Uliassi (bio info only in Italian sadly), the last salty chef to take the floor in the morning session, shares the honour with Moreno Cedroni of having put Senigallia on the map of Italian gourmets: his homonymous restaurant is considered one of the most interesting destinations by many critics. Those who follow this forum might have seen some discussion cooking of Uliassi in the past, here.

Uliassi started introducing his team, and then illustrated his cooking philosophy. “The cook should be a database of his clients’ tastes and to do so he should constantly train his palate. We Italians are privileged because, thanks to the richness in microclimates and products, we are steadily in practice”.

The dishes prepared and offered to the public gave a nice impression of Uliassi's style: salt cod with orange peel, acid cream and Tropea onion, a fresh example of an “uncooked cooking” to pay homage to Vissani; tuna fish with fried dried Calabrian peppers, quince jam (presented wittingly as prepared according to “the study of a cook’s mother”) and a sprinkling of Bottura’s balsamic vinegar (above); “beccafico”, that is salt cod with figs and olives.

-

For his appearance at Identità Golose, Scarello revisited to classics. His frico is destructured and reassembled, to preserve the individual contribution of each ingredient: dried onion, to improve its digestibility, potato soup, as carrier of flavours, and cheese enclosed into ravioli.

"Destructured," Alberto?

Has gastronomy gone to bed with de Saussure and Roland Barthes?

Meaning? After grating and cooking the Montasio, the frico is then chopped and mixed with other ingredients stuffed into the ravioli?

Hey, don't complain with me

, that's the way Scarello calls his frico! Actually I think the term has been abused by Italian chefs in the past... and still is, it would seem. Maybe deconstructed would give a much better feeling of the idea.

, that's the way Scarello calls his frico! Actually I think the term has been abused by Italian chefs in the past... and still is, it would seem. Maybe deconstructed would give a much better feeling of the idea.He simply means that all the ingredients are prepared separately and reassembled on the dish to create the feeling-taste of frico. The idea being that of offering cleaner tastes for each single ingredient: I cannot say that I tasted many examples where this really seems to work.

Forte, as I had mentioned before I never dined at Cedroni's place: Senigallia was not exactly close nor on my usual tracks when I was living in Italy, and it is even further now that I moved. Also, I feel ambivalent whenever I read Cedroni's menu, which I do from time to time: some dishes sound incredibly inviting, others way the opposite.

-

Your post and Albiston's are interesting. We went to Cedroni's place because a good friend of ours... who is a very good friend Cedroni. So, on the night we went to his restaurant, we were treated like royalty. We talked during the service, both with him and his wife (both extremely charming) and then talked at length after the service was over (he showed us his new building projects and it was clear he wanted to go to another level). It was during this conversation that he told us that he was Portuguese and told us the differences he saw between cooking in Portugal and cooking in Italy. His wife is Italian.

Perhaps he was joking around with us, ala the green bread in the bread basket, but he made no pretense that he was Italian. Moreno, his Christian name, is not an Italian name.

Now I'm curious as to what the real story is.

Intriguing story. So much so, that I went on and asked a few of my friends and contacts working in the Italian gastronomic scene about what they though. All of them told me that to their knowledge Cedroni is 100% Marchigiano; no one had ever heard anything about Portugal before.

I am somewhat puzzled.

-

The afternoon's session of Identità Golose opened with a thematic session on Friuli, with talks from three of the region's most interesting young chefs on the revisitation of tradition.

Andrea Canton, first speaker of the afternoon, is the chef of La Primula, near Pordenone, a restaurant which has been in the hands of Canton's family since the late XIX century. Like his colleagues, Canton concentrated on one particular side of Friuli's traditional cuisine: spices in his case, introduced to the local cuisine through the historic mittel-european connections of the region.

Canton gave a personal twist to the traditional plum dumpling, covering it in an incredibly fine julienne of cinnamon flavoured dough, frying it and then serving on potato pureé. Pan fried goose liver was paired to a sauce of mulled wine and to brovade (fermented turnips). Finally Canton discussed how to steam distill spices to obtain aromas ideally used in fonds and sauces.

Emanuele Scarello's restaurant Agli Amici, in Godia near Udine, is considered by many as the best destination in Friuli. Scarello is also the most creative and playful chef in the area, always ready to test new uses for long known ingredients and yet still respectful of tradition: next to his creative menu diners can find a traditional selection of classics, adapted to today's tastes.

For his appearance at Identità Golose, Scarello revisited to classics. His frico is destructured and reassembled, to preserve the individual contribution of each ingredient: dried onion, to improve its digestibility, potato soup, as carrier of flavours, and cheese enclosed into ravioli. For the classic buzara, a traditional fish soup of the area, Scarello decided to highlight the freshness of his ingredients laving the scampi raw, serving the tomatoes as jelly and the peppers as sorbet.

The small incursion into Friuli's revisited culinary tradition finished with Attias Tarlao, the young chef of All'Androna in Grado. Tarlao started extremely young yet his career is still at its beginning, though very promising ones at that. The menu at Androna is very much centred on the fish available every day at the local market, an ingredient for which this young chef feels a clear affection.

Not surprisingly, the three dishes proposed at Identità Golose were focused on this ingredient. First the brodetto: in the classical version this fish "soup" is served with white polenta. Tarlao changed the presentation, turning the dish into a sort of Easter egg. The polenta is dried into hemispheres and used to form a "pod" enclosing the fish brodetto. The equally classic soles "in savor" keep their essence in their new presentation (above): served as filets with a picolit sauce and a "coffee shot" of toasted pinoli. The tuna tonnato, a play on the more traditional veal tonnato, was cooked with a blowtorch on one side only, holding rosemary branches between fish and flame, to obtain an aromatic and slightly smoked flavour.

After Friuli it was time for a visit to nearby Slovenia with chef Tomas Kavcic of Gostisce Pri Lojzetu in Vipavaska. Salt was the real star of this talk, with Kavcic discussing the use of a variety of flavoured salts and a method which permits to use salt slabs to cook "a la plancha". Through this method food gets seasoned while cooking, as demonstrated through "trip to Pirano" where the salt of the local quarries is used as cooking tool and seasoning for the ingredients of the area, such as squid, bacon and sardines.

The day's talks culminated with Jordi Herrera of Manairò in Barcelona. Herrera is known for his technical cooking "tricks", sometimes at the cost of people forgetting his real ultimate goal as a cook: perfecting cooking methods through new tools and methods.

For his appearance at Identità Golose, Scarello revisited to classics. His frico is destructured and reassembled, to preserve the individual contribution of each ingredient: dried onion, to improve its digestibility, potato soup, as carrier of flavours, and cheese enclosed into ravioli. For the classic buzara, a traditional fish soup of the area, Scarello decided to highlight the freshness of his ingredients laving the scampi raw, serving the tomatoes as jelly and the peppers as sorbet.

The small incursion into Friuli's revisited culinary tradition finished with Attias Tarlao, the young chef of All'Androna in Grado. Tarlao started extremely young yet his career is still at its beginning, though very promising ones at that. The menu at Androna is very much centred on the fish available every day at the local market, an ingredient for which this young chef feels a clear affection.

His reflection on cooking method started from grilled sardines (above). The inspiration came after tasting an extremely aromatic but overcooked version of the dish, followed after a short interval by one prepared Japanese style, perfect in texture. To mix the virtues of the tow methods Herrera cooks his fish with a blowtorch through a screen of thyme which gives the fish a particular aroma. He went on to demonstrate his "internal heat" method injecting steam through a probe directly into a lobster, for example. The speed and neutral taste obtained through this technique allow to maintain a particular aromatic purity of the ingredioent. Finally Herrera demonstrated how his “nail barbecue” can be used, together with a blowtorch, to transmit heat in a uniform way to the ingredient, a beef filet in this case.

-

Don't understand about what you don't get about Cedroni being Portuguese? It is quite simple. Cedroni is from Portugal. I don't believe the info you have is correct. Cedroni is not from Sengallia and has not spent most of his life there.

Might be that I am wrong, but all the sources I have found say he is from Le Marche, born in 1964 in Ancona, that he attended the nautical school there, graduating in 1983, and that he opened La Madonnina, at the time a simple pizzeria ristorante, in 1984. There's no mention of Portugal whatsoever anywhere I looked... that's what I don't get.

But maybe Cedroni is trying to hide his murky Portugese past

, so I was trying to find out on which information you base your claim.

, so I was trying to find out on which information you base your claim. -

...

To summarize, I think Peskias is indeed one of the most talented chefs we have in Greece, but his talent will go to waste if he falls in the "show-business" trap. This is a very large trap in Greece, where people mostly go to the expensive restaurants like "48" to see and be seen and do not really care about the food and the wine.

My suggestion to any talented chef in Greece today would be to open a restaurant where people who like good food can go without having to spend more than they would in Arzak or Mugaritz! There they should offer creative and inventive cuisine that is open to critique and public discourse, and not the domain of a small group of socialites and journalists.

athinaeos, thank you for the feedback and the well put points. Taste differences aside, I am also suspicious of the show-biz side of restaurants when it becomes more important than the food itself: I like nice presentations as anyone else, but I am more ready to excuse a dish that looks bad but tastes good than the other way around. It is undeniable that show effects are on the rise, and I am curious to see if they are here to stay –will we be seeing Baroque creations a la Careme from molecular gastronomes soon?– or if it is just a fad.

What I am less sure about is your point on critique and public discourse, or rather only the latter. Critique is an integral part of the daily life of chefs, I imagine, yet I can hardly see a chef submitting himself freely to public discourse.

Well done again, Alberto. Thank you. Any idea how Cracco winds up with such thin slices of fish?What sort of reaction did the Italians and Italian press have towards Wylie?

I have really no clue about how Cracco produces those sheets, though I don't think it is done with Wylie's method. That one is pretty specific to proteins, while Cracco mentioned he is planning to do something similar with vegetables and even pastry ingredients. Also Cracco's fish sheets are, according to those who tasted them, very different, especially in texture, depending on the starting ingredient.

Living abroad I only get snippets of information about what appears on the Italian press, yet my impression is that the whole discussion on Adrià's 23 point manifesto obscured pretty much the rest of Identità Golose, not only Wylie. From what I have heard from those four or five people I know who attended, Wylie's dishes intrigued them or left them quite cold, depending on their position on today's culinary avant garde. Wylie does seem to be one of the best known US chefs though, after Keller, Trotter and Walters.

-

I've only been to Cedroni's place once, a couple of years ago. He wasn't fully into his laboratory food yet and his cooking showed a mediocre amount of skill. What really turned me off was the green bread; seems to get me every time. What was this, Saint Patrick's day in Senigallia? Cedroni is not italian; he is Portuguese. Perhaps that is why he's confused about that famous Italian dessert "bounty di seppia” a chocolate covered cuttlefish-coconut ganache praline."

I have to admit that, while I have never eaten at La Madonnina del Pescatore, I do find some of Cedroni's creations somewhat puzzling, at least on paper, and I cannot imagine how they would work at all. A friend that visits him at least twice a year, and is clearly a fan of his cooking, strongly insists that if you haven't tried them you should not judge: since you have, I will add your opinion to my suspicions. On the other hand there are a few dishes of his that sound very intriguing.

I don't get what you mean with Cedroni being Portuguese: as far as I knew he is from Senigallia and has spent most of his life there.

-

After an opening day full of awaited guests and discussions about techniques, ingredients and food tradition, Identità Golose continued with a stimulating second day: the morning session centred on fish would be opened by an off programme from the Dossier Dessert speakers, while the afternoon session was dedicated to Friuli (and neighbours) finishing off with another special Spanish guest.

Heinz Beck, of the freshly Michelin three starred La Pergola in Rome, opened the day's works with a sweet note. The Bavarian Beck landed the job of chef of the La Pergola restaurant (part of the Cavalieri Hilton Hotel in Rome) after a successful career back in his native Germany which culminated in his three years as pastry chef for the famous Heinz Winkler in Aschau. Yet today few would guess his nationality by trying his creations: through the years Beck succeeded in giving his cuisine an Italian sensibility and style.

The two dessert prepared for Identità Golose are part of the seven courses that make up his signature Grand Dessert. He started with his apple and eggplant tartlet, a homage to Beck's Sicilian wife, continuing with a "fluffy" torrone (above), prepared as a foamed mousse and served with a tuille of dried fruits. Beck went on to explain his concept of taste in desserts, where he likes to put savory and sweet side by side, while reducing the sugar content rather than increasing it, to avoid getting a saturated and tiring taste.

Moreno Cedroni, chef of La Madonnina del Pescatore in Senigallia, managed to nicely abridge the sweet and savory parts of the morning section with his "Cuttlefish, from savory to sweet" talk. Cedroni is certainly one of Italy's most original chefs. In the past years he has offered an Italian version of sushi (predictably called susci) to his guests, experimented with fish as ingredient in all his forms and fused the concept of panini and tapas together, just to mention a few. Apart La Madonnina restaurant, he also runs a fish delicatessen in the center of Senigallia –selling cured fish products, sauces and tinned goods produced by Cedroni's team– and a susci bar, Clandestino, on the Portonovo beach.

Cedroni explained how cuttlefish can be an extremely versatile ingredient that can be used for both savory and sweet dishes and went on to demonstrate two dishes created by playing with this idea. “Cucciolone di seppia” (above), the savory take on cuttlefish, is a dish inspired by Adrià and shaped as a famous Italian industrial wafer-ice cream called cucciolone: two cuttlefish tuilles hold a filling of tomato flavored cuttlefish meat “mozzarella”. His take on dessert was equally playful: “bounty di seppia” a chocolate covered cuttlefish-coconut ganache praline, imitating the famous snack bar. Pastry work, stated Cedroni, was instrumental in his learning about accuracy in cooking, an accuracy which he uses to let his fantasy roam free.

During the three days of the congress one of the recurrent themes was that of pasta made out of unusual ingredients, especially fish. Like Caputo before and Dufresne after him, Carlo Cracco, of Cracco-Peck in Milan, focused his appearance on stage on this idea. Cracco is one of the so-called Marchesi boys, i.e. that group of chefs coming out of the kitchens of the famous Gualtiero Marchesi, many of which have gone off to pursue fame and glory on their own. After an experience as chef of Clivie in Piovesi d'Alba, in 2001 Cracco opened his Milanese restaurant inside the structure of the famous gourmet grocery Peck, quickly becoming a favourite of the critics.

Cracco's "Quaderno di mare" (sea-book), thin sheets of fish "pasta" made with just fish meat and a little olive oil, was born as a sort of ironic idea “... by chance, as we were looking through paper samples for our new menus. These sheets are just the playful base that can act as a base for many recipes.” On this occasion the chosen recipe was a seafood salad (above), in a minimalist and refined composition made of leaves of “pasta”, all with its own particular texture, made with octopus, shrimps, scallop muscle and corral, and white and black cuttlefish, on a bed of vegetables, unsalted and only sprayed with a little parsley oil.

Anthony Genovese's performance took a step beck form the technological advances of cuisine and focused the attention back on the plate. Genovese, know the chef of Il Pagliaccio in Rome, started his carreer in France were he learned the nuts and bolts of restaurant cooking, From there Genovese's career never stopped, bringing him to Ravello's Rossellinis before his Roman move.

Through his French bases, Italian gastronomic roots and a love for Asian spices, Genovese has developed a personal cuisine: “There's a lot of talk about minimalism”, he said, “but I am closer to baroque because I like uniting all the elements of taste into one dish.” Genovese's style is quite noticeable in his colourful and contrast-rich dishes, like his revisited lobster curry, served with a basmati rice “turnover”, thinly sliced pig ears and an unusual caramel bisque.

The last speaker of the day, Wylie DufresneWylie Dufresene of NYC's WD-50, needs little introduction here on the eGullet's Society fora: discussion over his cooking abound, be it when directly focused on wd-50on WD-50 or regarding his use of enzymesuse of enzymes to prepare shrimp spaghetti, spaghetti made out of shrimps that is.

Dufresne demonstrated just a few of his better know dishes, showing how versatile shrimps can be. Apart the aforementioned spaghetti he talked about his shrimp cous cous, made of shrimp “grains”, and cannellioni, where the flattened out shrimps become the pasta casing, and how the same starting material can be transformed, often without the need of extreme technological solutions.

-

I’m pleased that we agree to disagree.

I find it makes the discussion more productive and I think I always have something to learn form hearing the other party's opinion... in this case I think that the essential difference between us might be not as big as it might seem, as you will see immediately below.

Other than a handful of chefs, who are those that have been around for ten years? I’m not disputing that there will be room for some, it is that I believe that it will be very few, because so few Italians who enjoy alta cucina and have the money to eat it, will be frequenting restaurants serving “modern Italian haute cusine.”I don't dispute that only some will make it –that was exactly the sense of my first paragraph in the previous reply– I feel the difference is more in the numbers. I think a handful is quit a pessimistic prediction and feel the customer base is somewhat wider than you suppose. Maybe I'm wrong, but it might also have to do not so much with the fact that we know different Italians, but that we know different generations of Italians: most of the restaurant goers I know are in the 25-40 age span and my impression is that they are quite attracted by the new young chefs that are around.

To tell you the truth, I have the impression that if we had this discussion face to face, and maybe with some nice food and wine before us (I promise, no foams

) we might find out we see things more similarly than this argument would make us suppose.Didn’t understand the paragraph beginning with “I have extracted…” I have in fact tried a number of the restaurants, so my comments are not based on “my idea of it.”

) we might find out we see things more similarly than this argument would make us suppose.Didn’t understand the paragraph beginning with “I have extracted…” I have in fact tried a number of the restaurants, so my comments are not based on “my idea of it.”Sorry if it sounded like an accusation of kind, it was really meant as a genuine question.

When I went to my fish store (Volpe, one of the best I’ve ever seen in Italy i.e. a vast selection of pristine fish and shellfish; they do a large wholesale as well as retail business and although very expensive, the quality and selection are unbelievable) in Viareggio this morning and looked at the sparnocchi still dancing in the box around and the occhione barely out of the water, I couldn’t help thinking what kind of foam I was going to serve with the sparnocchi and how I could weave guanciale croccante into the dish with occhione. LOL. As we say in Forte… chacun a son gout.Foams are so last year, as soon as you'll read the next session of identità golose (coming up tomorrow) you will know that the thing to do is turn them into sheets of fish "pasta"

... though could perfectly imagine a couple of infusions that would go great with raw sparnocchi...Paraphrasing Kuhn, "the paradigms must be sufficiently unprecedented to attract an enduring group of practitioners away from competing cuisines and sufficiently open-ended to leave all sorts of problems for the redefined group of practitioners (and their students) to resolve".

... though could perfectly imagine a couple of infusions that would go great with raw sparnocchi...Paraphrasing Kuhn, "the paradigms must be sufficiently unprecedented to attract an enduring group of practitioners away from competing cuisines and sufficiently open-ended to leave all sorts of problems for the redefined group of practitioners (and their students) to resolve".Interesting point, my only problem with it is that I don't really see competing cuisines. Although I might have somewhat forced my opinion during the discussion with fortedei, I love traditional Italian cooking probably more than its more extreme modern incarnations, yet I'd find a dining scene without the latter terribly depressing. That they both can co-exist is refreshing, though I am aware that not many see it that way.

Unfortunately I have to put on my kill-joy hat and ask everyone to stick a bit more to the theme of this thread. While discussions on the general situation of Italian dining are fascinating and to a point inevitable, it would be better if we did not stray too much OT and went back to Identità Golose.

I'll kick off picking up the chance to ask more about Peskias. Have you ever eaten at his place, athinaeos? Is his reputation abroad as "guru" of modern Greek cuisine justified?

-

Well, fortedei, you certainly have made clear that you have a grudge with modern Italian haute cuisine

. There are quite a few interesting points you raise, though, as you can imagine, I see things quite differently.With regard to the topic of modern haute cuisine and Identita Golose:

. There are quite a few interesting points you raise, though, as you can imagine, I see things quite differently.With regard to the topic of modern haute cuisine and Identita Golose:In my mind, very, very few, if any, of these “new young Italian” chefs, will stand the test of time in their present incarnation.

I think we can pretty much bet on that: when there's a nascent movement, be it artistic, scientific or culinary, you do tend to have a lot of pretenders to success, but only a few will succeed. Yet I hardly agree with the reasons you give.

There are three reasons why I believe this to be so. First, the Italian public, those few who can afford to go to the restaurants which will serve this “modern haute cuisine”, will, if you’ll pardon the pun, not stomach this type of food.I'd be interested to know why you think that is the case, apart the fact that you are quite clear about the way you feel about it. Personally I feel that you underestimate the rising interest for haute cuisine I have been noticing in Italy. Those that are interested in haute cuisine definitely will go for the modern take, the problem might be more on how many of these there actually are.

Secondly, many of these chefs really don’t know the fundamentals of food, are ill prepared or clueless with regard to technique, and are just copying something “of the moment.”I wonder who you are really speaking about. The chefs that took part to identità golose or copycats? Let's be honest, Italy lacks a serious culinary school, though that might be slowly changing. Yet, if you look at their CVs of many of the best young chefs, you will notice that they often had years of experience in the kitchens of top Italian or foreign chefs, not just a few stages here and there. I doubt they are as clueless as you paint them. If you look at their copycats, you're clearly right, and I agree that there is a large number of these.

Lastly, many of these chefs have no idea how to run a restaurant and have had scant experience in seeing what it takes to do so…doing short stages in many restaurants to get “lines on your resume” so that a few journalists can anoint you as the hot new talent, counts for nothing on a Thursday night in late November with the nebbia rolling in, and the only table filled is a deuce.The fact that chefs often lack the economic knowledge to know how to make a restaurant economically successful is no big mystery to my eyes, that's why restaurants that manage to live long (and prosper

) often rely on a partner with a good grip of the business side of things. Some of the restaurants of this new wave will definitely have to prove they can stand time, but others have been around for over ten years: wouldn't you agree that the latter chefs have proved they can indeed run a restaurant?France, of course, had much the same thing with nouvelle cuisine in the 70s; the results were perhaps a bit better, but not by much. While some things remained, lightening of dishes for example, the simply awful combinations, which made absolutely no sense from a conceptual standpoint (and even worse from a taste standpoint) disappeared.

) often rely on a partner with a good grip of the business side of things. Some of the restaurants of this new wave will definitely have to prove they can stand time, but others have been around for over ten years: wouldn't you agree that the latter chefs have proved they can indeed run a restaurant?France, of course, had much the same thing with nouvelle cuisine in the 70s; the results were perhaps a bit better, but not by much. While some things remained, lightening of dishes for example, the simply awful combinations, which made absolutely no sense from a conceptual standpoint (and even worse from a taste standpoint) disappeared.I have extracted this section from the whole paragraph about nuova cucina, because it highlights your prejudices. You cut the positive sides short and spend a lot of effort on highlighting the shortcomings of nouvelle cuisine or nuova cucina. So let me play your game in reverse

: Novelle cuisine might have produced some abominations but it radically changed haute cuisine. Not only lightening the dishes, but giving a greater importance to the aesthetic of the plate, changing the way the courses of the meal are organized and introducing methods that are taken for granted today (just think of juices and infusions instead of starchy sauces). Might I also remind you that a few of those chefs that were around in Italy in the 80s and early 90s have all but disappeared: people like Iaccarino, Vissani, Pierangelini, not to mention Marchesi, are still there running their restaurants with quite a lot of success. Did they evolve from nuova cucina? Sure, but not, contrary to what you stated, in the direction of regional food.Today, in the food area, the foodies (what an awful word; why do they insist on calling themselves foodies) and some of the press make a big deal of avant garde chefs (most of them are no more than cooks and I don’t use the word cook in a pejorative sense). The main problem as I see it is that the Italian public in general is not going to care about the modern haute cuisine and/or laboratory food as discussed in this forum.

: Novelle cuisine might have produced some abominations but it radically changed haute cuisine. Not only lightening the dishes, but giving a greater importance to the aesthetic of the plate, changing the way the courses of the meal are organized and introducing methods that are taken for granted today (just think of juices and infusions instead of starchy sauces). Might I also remind you that a few of those chefs that were around in Italy in the 80s and early 90s have all but disappeared: people like Iaccarino, Vissani, Pierangelini, not to mention Marchesi, are still there running their restaurants with quite a lot of success. Did they evolve from nuova cucina? Sure, but not, contrary to what you stated, in the direction of regional food.Today, in the food area, the foodies (what an awful word; why do they insist on calling themselves foodies) and some of the press make a big deal of avant garde chefs (most of them are no more than cooks and I don’t use the word cook in a pejorative sense). The main problem as I see it is that the Italian public in general is not going to care about the modern haute cuisine and/or laboratory food as discussed in this forum.Come on, that's a superficial comment. I never heard anyone claim that haute cuisine is or ever will be a mass phenomenon. The last time I looked Mac Donalds was the most succesfull franchise in the world, not Ducasse's restaurants. Haute cuisine is inevitably addressed to a customer base which is made up by food lovers/gourmets/foodies (call them what you prefer, the essence does not change) and those who use fine dining as a status symbol. You repeat this point later in your post when you mention Beck and Alajmo, yet this consideration adds or subtracts little to the eventual success or failure of these new chefs. Their future depends on those clients that would be interested in their cuisine or at least curious about it anyway. Most of those that love trattorie don't and will not visit such places. Having had this kind of discussion quite often I have know from experience that only a minority of my fellow Italians base their choice on the actual style of cuisine of the haute cuisine restaurants: most have no idea of what these restaurants serve), but rather dislike these establishments because the portions are small and the prices are high.

The whole concept (and I know many of you don’t agree) is ephemeral in nature and quite frankly to me, very unappealing (so that you can get some idea of where I’m coming from and of my prejudices: I live in Italy six months a year and first started eating in Italy in the early 70s, going to places like (Beppe) Cantarelli and then a bit later becoming very friendly with Franco Colombani, the group of chefs in Linea Italia and others. Among my closest friends in Italy is arguably the best known Italian chef. I’ve seen the good and the bad, mostly good, over a long period of time and in a great many restaurants).I have no problem accepting the fact that you find the new avant-garde unappealing, it is a matter of taste after all. What I do have a problem with is the way you are dismissing the whole thing. I wonder how many of these "new" restaurants have you tried, i.e. if your opinion on their cooking is based from direct experience or your idea of it. My impression is that you are grouping all these new chefs under the ego-fulfilling creative type. If so you might want to reconsider: some of these new chefs fall indeed in this category, which does not make them less interesting to me, yet others manage to reinterpret regional cooking in a novel yet respectful way: Gennaro Esposito's Parmigiana di pesce bandiera, for example, is a creative dish, yet one deeply Neapolitan and respectful of tradition.

BTW, would you mind telling us who the best known Italian chef is? In Italy or abroad? Vissani? I'm quite curious.

Yes, the foodies and the press make a big deal of “modern haute cuisine,” but it is simply not important to the Italian who can and does eat in, for lack of a better term, restaurants that either are, or aspire to be, well above the norm ( the norm being a simple ristorante or trattoria). Over the long term those places will be patronized mainly by Americans (both foodies and non foodies), a few Italian foodies and certain Italian food journalists, and a few Germans and Swiss.I beg to differ. This might be the case with places like Enoteca Pinchiorri or Al Sorriso, whith their three Michelin stars and the like. But go to places like Il Duomo in Ragusa, Uliassi in Senigallia or Pierangelini's Gambero Rosso: I am confident you would find quite the opposite. The truth is that famous restaurants that are near to main tourist attractions (the classical Firenze-Venezia-Roma triangle) definitely rely on foreigners for their main income, yet those places that are off the beaten track are visited mainly by Italians.

And so too, would young chefs remember that it is what is on the plate, not what is in the press, that matters. If not, one has to say, the emperor has no clothes.We can definitely agree on that, only let's not forget that taste is subjective. I'd definitely choose Pierangelini over Pineta any time, and I'm sure you'd do the opposite. That doesn't decrease the respect I have for your opinion... it is just far away from mine.

-

I don't wish to take this discussion off track, so Alberto please pipe up if you think a new thread is in order. However, I discovered the Academy of Italian Cuisine while searching for web sites that feature Italian regional cooking. I am curious and would like to know if this group intersects with Identità Golose in any way, or how it relates to the Slow Food movement...if it does at all. Is Slow Food considered too political whereas other groups wish to distance their aims and activities from anything that smacks of activism?

A little OT is OK, I think. After all we've discussed quite a bit about Slow Food and finen dining so taking the Accademia Culinaria to talk about Italian cuisine is fine, as long as it does not hijack the thread

.

.The Accademia has, as far as I know, nothing to do with Identità Golose or Slow Food. It is probably the oldest Culinary association in Italy and has a long tradition of culinary events. I have never had any direct contacts with them, but what I hear from friends who are foodies or chefs is not exactly too enthusiastic and depicts this association as somewhat old fashioned and out of touch with modern Italian cuisine. For some of my foodie friends their restaurant guide is particularly hilarious though I never managed to understand why. My personal impression is that they like to keep an erudite and exclusive profile no matter what.

I don't think that Slow Food is really seen as too political, at least in Italy. Apart their no-global tendencies, they are happy to get the help of any politician throughout the political spectrum who is interested in their ideas. The last Agriculture Minister of the Berlusconi government, coming from the right wing party Alleanza Nazionale, has been a strong supporter during his period in charge. If slow Food is criticized in Italy, it is for quite different reasons. Their sort of messianic we -are-better-than-thou attitude does go on a lot of people's nerves, and the way they hand out their presidia, the "gastronomic reserves" that protect particular products, at times is undeniably more political-economical (slow food receives a fee for the Italian presidia) than the association would like to admit.

-

John, Kevin and Pontormo,

quite a few interesting comments about Slow Food and the critiques to Adrià's 23 point manifesto. Although Slow Food has little to do with Identità Golose itself , it has a lot to say in the way Italian see ingredients and cooking in general, so I just wanted to add a few comments to what you wrote here and there.

Once again, a fascinating report, Alberto, and good to see coming out of Italy.The cuisine of terroir is also good, although the concept is hardly novel - not that it needs to be. A recent meal at Chez Panisse Cafe in San Francisco is a prime example of this from within the United States. It is no wonder that Alice Waters is so respected in Italy and within the Slow Food Movement. Speaking of Slow Food it is heartwarming for me to see Slow Food and alta cucina sharing common ground. I have personally never seen them as opposed although I know others who have.

What you say about the cuisine du terroir is definitely true of Italy too: long established top resatarants like Dal Pescatore or even the more creative Don Alfonso 1890, have been doing terroir inspired cuisine since over two decades. I am fascinated form the new takes younger emerging chefs (Italian and not) are developing on this simple concept.

What you say about Slow Food is funny, in a way. I think there are indeed many who continue thinking that Slow Food and fine dining do not go together. Slow Food 's decision to cover only traditional trattorie with a bill up to 35 euros per meal in their Italy eating guide Osterie D'Italia also helps spread this prejudice IMO. Yet this is the product of a misunderstanding of Slow Foods mission. Carlo Petrini himself (founder of Slow Food) more or less stated some time ago that he enjoys fine dining like anyone else, only sees this as something that most people will reserve for special occasions, so Slow Food is more interested in everyday meals and ingredients.

It's fascinating how what you and Docsconz discussed dovetails with the negative reaction from journalists to Adria. Since you mentioned this, would you happen to know what was the consensus around the other "foreign" chefs? Was it particularly pointed just towards Adria and what he represents?Pretty much yes to your last question: inevitable when you're considered the number one chef in the world.

Again one has to separate the prejudiced critiques from the honest and thoughtful ones. Those who attacked Adrià out of prejudice belong to that fraction of the Italian press which I would call "the nationalist party": critics who have ever hardly been abroad, know little of the fine dining scene outside Italy and maybe France, and firmly believe that Italian cooking is the best in the world. For them nothing is better than having a go at a celebrity foreign chef to prove their point, unfortunately they cover themselves in ridicule when making so. When an affirmed journalist Lie Edoardo Raspelli attacks Adrià for his foams, he just shows he has not done his homework. I've never eaten at El Bulli and yet I know that Adrià has moved away from the foam period years ago: a professional journalist should know better.

The well thought critiques to Adrià's manifesto also sprout from his position as worldwide culinary avant-garde leader, but, as mentioned by Garcia Santos, that is probably exactly Adrià's goal. He presented HIS philosophy and it is normal that others might see things differently and reply to that.

From the little I could catch, not having been in Milano, I think that most of the foreign chefs did tickle the curiosity of a certain part of the public, especially the chefs and travelling foodies attending.

I know people who think that Slow food is a bit reactionary and wish to go back in time.I have heard such comments quite often too, and find them deeply ironic. I wonder how many know that Slow Food was born in the 80s out of one of the many cultural associations (ARCI Gola) linked to the Italian Communist Party.

From my experience that is not the case at all. While preservation of culinary traditions is a central part of the organization, the main thrust is the preservation of biodiversity. That is to say that they consider it of paramount importance to protect and promote local variety, quality and uniqueness. Ther certainly is a political element of the organization that some people get entangled with, but I feel that that purpose is secondary and subservient to the culinary one.I'm not too sure about your last point, John. I think THAT just by reading what you wrote above it is quite evident that Slow Food has a strong political agenda connected to the general anti-globalization movement. Sure, it is primarily tied to food and food production, yet I would not say that their politics are subservient to their culinary goals: to me they go hand in hand.

The reason I feel that these aims of Slow Food is consistent with haute cuisine is that much if not all of haute cuisine also depends on the quality, variety and uniqueness of the ingredients used including hypermodern chefs like the Adrias, Blumenthal, Achatz and Dufresne. There is nothing in Slow Food that I can see that is against creativity so long as the traditional foods and techniques are not forgotten in the process. A recent article in Slow was all about how today's traditions were at one time innovations. If everyone started cooking from one palette of ingredients in one style that would be opposed by the Slow Food Movement, but individual creativity within or without a tradition using varied and quality ingredients is from what I can see totally consistent with the tenets of the Movement.Very good point, though one should also underline the differences between the slow food philosophy and a certain kind of haute cuisine. The resistance to Adrià's idea of using industrial goods is quite easy to conceive if one thinks that this concept is quite opposite to Slow Food's idea of promoting small local artisan productions. On top of that, one central reasons of contrast between the cuisine du terroir brigade and some top chefs is the issue of seasonality. Real cuisine du terroir is inevitably seasonal, whereas some chefs tend to compromise that in favor of their own creativity.

Since we are talking about cusine du terroir, I was wondering if anyone out there had a chance of eating at Dahlgren's Bon Lloc before it closed. The feeling I get from his talk at Identità Golose is one of a very enjoyable and ironic cuisine, and I was wondering how that compares with the reality of his cooking.

-

The opening talk of the afternoon session brought on stage the chef most awaited by the public: Ferran Adrià. Adrià and his restaurant El Bulli need little presentation: a word fame no other chef can match make El Bulli the hottest reservation worldwide. (For more info on Adrià you might want to look at our Q&A with him and our Daily Gullet excerpts from El Bulli 1994-1997 parts one, two and three.)

At Identità Golose he presented the 23 points describing the Bulli’s philosophy, which have appeared in the eGullet Society forums before, here. These defend the strengthening of the relations with scientists and the food industry but also the protection of the original tastes of ingredients and the link with the territory. Adrià predicts that in the future, cooking will be increasingly free: there won’t be hierarchies between sweet and salty, rich and poor ingredients and different types of courses. Taste in particular will come from tradition, with its experienced combinations, as well as from the inspiration of the cook, with the challenge of unusual combinations. “Mousses and simplicity are just a small part of the Bulli: this is the manifesto showing what we are at the moment. In 2006 the new book about the restaurant will be published and these points will be certainly included in its 8000 pages”.

Among the techniques demoed, Adrià stressed the importance of lyophilization which allows to explore crunchy and dry consistencies in salty dishes. The olive oil caramel, made by 3 people in one hour, showed how El Bulli is firmly linked to an artisan dimension.

Taking a step outside the tale of what happened at Identità Golose, it is maybe worth mentioning the reactions that Adrià's talk caused among the Italian press and chefs. These ranged from mild critics, in particular from fellow chefs, to downright jeering from a part of the gastronomic press. Ironically, more than causing a genuine discussion on Adrià's ideas, this has worked in giving a pretty clear picture of the gastronomic prejudices of many well-known Italian journalists. Although maybe not the prime cause, it is hard to believe that the media clamour has not had some role in this editorial from Rafael Garcia Santos. If we ignore the prejudiced attacks to the 23-point manifesto, the main critique

coming from the Italian gastronomic world to Adrià is in his backing up of industrial products in haute cuisine.

The burdensome task of following Adrià's talk fell on the shoulders of the Cypriot chef Christoforos Peskias. Chef of the stylish 48 the Restaurant in Athens and with experiences in Charlie Trotter's kitchen in Chicago, Peskias is considered by many the most eminent exponent of new Greek haute cuisine. He approaches his creations through reinterpreting tradition, playing with the memory of taste and modern technical methods in cooking.

He intrigued the public with his dishes, revealing the unknown world of modern Greek cuisine to the Italian public. Peskias presented two dish which exemplify his approach to cuisine: a modern version of rice-stuffed tomatoes , presented in the shape of sushi (shown above), and illusionistic tomato eggs made of egg yolk jelly, carrot juice made round like the yolk and heated up herbs served with tomato concasse.

Vittorio Fusari, chef of the Michelin starred Il Volto in Iseo, discussed the meaning of tradition in the “cucina del territorio” or cuisine du terroir. Fusari has had an eclectic past before becoming a full time cook. He opened the original Il Volto with some friends in 1981, after having studied philosophy and having worked as a station superintendent. His approach is best described in his own words: “The subject of cooking should be the dish, which represents the means of communication between the cook and the client sitting at the table. My goal is to make cooking as local as possible, expressing the identity of the territory and supporting its gastronomical resources”.

Fusari went on to demonstrate his philosophy through three dishes of his repertoire. Apart his signature potato puff-pastry with caviar, he prepared a “summer risotto to be eaten vertically”, made of grana padano cheese ice-cream, saffron jelly, classical saffron risotto (made with Bellavista spumante) and a grating of parboiled bone marrow (above). As closure to his talk he presented a dish of fresh and dried sardines with polenta, tomato sauce jelly and a grating of foie gras cooked at low temperature, combining sea and land ingredients as well as rich and poor ones.

The Swedish Mathias Dhalgren followed with his talk “Thinking-creating-showing-saying: a bad idea is still an idea”. Dhalgren, one of the leading personalities of the new Scandinavian cuisine, was chef of the Bon Lloc restaurant for ten years. He recently decided to close the restaurant and take a year off to travel around with his Spanish wife. Dhalgren's idea of cuisine has changed during the past years: “Before I thought that technique was everything” he says “Now I think that ingredients are everything”.

The dish that accompanied his talk are a clear proof of his beliefs. The “taste of the Swedish cow” is a trip around an encyclopedic animal: the fillet is matched to a milk, butter and cheese mousse, all products from the same animal. The “organic vegetable-garden” (above) is fragrant and recalls all the products of a field, vegetables, herbs, bulbs, berries, buds but also snails. “I spent my life cleaning salad from snails and now I put them back in again” he ironically commented.

Alfonso Caputo closed the day with his seafood dishes, where he tries to use at best the structure of ingredients, including fish-bones and entrails. Caputo is the chef of the Taverna del Capitano in Massa Lubrense, on of the best restaurants on the Sorrento peninsula.

Caputo's talk focused on fish based dough which is made exclusively of fish pulp steamed for 40 minutes at a temperature of 30°; it can be then cut in the most varied shapes and after long boiling, it is dressed with a common sauce. Its final consistency recalls “thick fish fillets, with a very intense taste”. It can be dried and kept for several months, as common macaroni. Among his creative innovations also a triple octopus dish, which uses the natural jelly of the mollusc.

-

Alberto, I will be looking forward to the installments with great anticipation. It is good to see Italian "alta cucina" awakening from a relative slumber.

While Italian cuisine retains a very strong reputation in general, the sense I have is that the reputation of Italian fine dining has lagged a bit behind Spain, France, England and the US among western oriented traditions. One reason perhaps is a perception, true or not, that Italian fine dining has had in recent years a tendency to be less inventive or innovative and to incorporate less from other cultures than some of its cultural competitors. If true, one reason may be that the Italian dining public has been rather conservative and that most foreigners going to Italy to dine are quite content with exploring the more traditional cuisines. It becomes almost a chicken and egg situation.Italy's reputation is largely for its traditional cuisine and attracts people looking for it and understandably so.

John, thanks for bringing up a whole lot of very interesting points. As long time follower of this forum you probably well know that we have discussed about Italian haute cuisine a lot in the past. I personally think that the slumber you refer to was often more apparent than not, having a lot to do with the lack of communication between Italy (and its top chefs) and the outside world. This is definitely changing, and Identità Golose is a welcome push in this direction. Yet it is undeniable that the last few years have been very exciting in terms of new young chefs developing ideas and cooking styles of their own.

Your chicken and egg analogy is spot on. I believe that top a certain extent we are ourselves to blame for this situation: most Italians dismiss fine cuisine altogether because it does not follow that familiar reassuring tradition they are used to. If a chef has to fight against something of this kind, you do tend to be less conservative, otherwise your restaurant risks having a very bad financial future, which explains the cautious behavior of many Italian chefs.

Yet some of the apparent conservative views that come across statements like Pierangelini's are more an indication of the different relationship Italian chefs have to their ingredients and a cultural love for simple things. In a sense that pretty much sums up much of our traditional cooking: simple dishes made with excellent ingredients. What many people ignore is that the best ingredients don't land in the kitchen of family-style trattorie, or only in a few of them. Instead they end up in the kitchens of a few top tier restaurants that are willing to pay for them and who can charge the prices that these products inevitably fetch. Furthermore I have had a chance to see what some Italian chefs do to get first class ingredients and that kind of dedication brings with it a great respect for the ingredients you are going to cook, just like Pierangelini pointed out. In a way, my feeling is that those Italian chefs that hold these principles as base for developing their own cuisine have their closest soul-mates in a certain part of the Californian culinary movement, especially that started by Alice Walters.

As such the climate is less conducive to developing a cuisine of culinary risk-taking. In addition, Italy's colonial past is less prominent than those of Spain, England, Portugal and France for example with fewer opportunities to incorporate disparate cuisines into the national milieu. Spanish, English, French and American high end cuisine has borrowed considerably from various Asian cuisines within the past 50 years or so. This is not as readily apparent in Italian cuisine.That is probably true. I am curious to see what will happen to Italian cuisine in the next 10-20 years, given the large numbers of African, Chinese and Sri Lankan immigrants we have acquired over the past decade.

Perhaps it is me, but I got the sense that some of the quotes like Pierangelini's sounded almost defensive: “Great cooking is made of virtuous steps more than technology. What I’m looking for is pushing ingredients to the limit in a natural way, a more intimate relationship with nature. In this congresses we talk about new techniques and unusual ingredients; in contrast I want to show the sense of simple things, because egg is the countryside”Even if a bit defensive, the approach is very Italian and sounds wonderful. If it leads to new directions of haute cuisine that are delicious and uniquely Italian that can only be a good thing for gastronomy.

That's what I believe too. I don't really care for a haute cuisine which is flattened out on ideas that spread globally: the "espumas for the sake of espumas" the solid cocktail kind of places excite me very little. Whatever the degree of technical innovation or creativity, I love the feeling of being able to sense the cultural background of the chef. For example: you can be a forerunner of molecular gastronomy, like Heston Blumenthal, and yet, just by looking at his menu you know he is British, and I really enjoy that.

-

Two of the chefs you mentioned seemed to take pains to emphasize promoting ingredients in a more "natural" sense and downplay technology. Is this then something that is in response to the Ferran Adria/molecular gastronomy movement?

Yes and no. There will be more on this in the post covering the next session, which starts with Adriá himself, so I'm not anticipating too much

. Let's just say that a part of Italy's gastronomic world, be it chefs, foodies and journalist, has a certain dislike regarding molecular gastronomy. Some people dislike the idea for pure principle, and yes, they see Adriá as a sort of demonic figure: most notable among them Edoardo Raspelli, former curator of the Italian Espresso restaurant guide and a well known food personality in Italy. Others have reserves, yet not so much on people like Adriá or Heston Blumenthal, who have the technical knowledge and experience to do what they are doing, but rather towards the way the movement is producing copycats of little skill or gastronomic sensibility. I think someone like Pierangelini targeted in his talk particularly the new generations of Italian chefs and warns them against following easy fashions.Is it endemic to the Identita Golose's purpose, or their own (the two chefs') personal beliefs?

. Let's just say that a part of Italy's gastronomic world, be it chefs, foodies and journalist, has a certain dislike regarding molecular gastronomy. Some people dislike the idea for pure principle, and yes, they see Adriá as a sort of demonic figure: most notable among them Edoardo Raspelli, former curator of the Italian Espresso restaurant guide and a well known food personality in Italy. Others have reserves, yet not so much on people like Adriá or Heston Blumenthal, who have the technical knowledge and experience to do what they are doing, but rather towards the way the movement is producing copycats of little skill or gastronomic sensibility. I think someone like Pierangelini targeted in his talk particularly the new generations of Italian chefs and warns them against following easy fashions.Is it endemic to the Identita Golose's purpose, or their own (the two chefs') personal beliefs?Definitely the latter, as you will see soon enough

. Paolo Marchi himself has always given me the impression of being a critic with little prejudice and open to novelties... as long as it tastes good.How much does this tie into the Italian nature of this congress, i.e., the affinity the Italians traditionally show for their own indigenous ingredients?

. Paolo Marchi himself has always given me the impression of being a critic with little prejudice and open to novelties... as long as it tastes good.How much does this tie into the Italian nature of this congress, i.e., the affinity the Italians traditionally show for their own indigenous ingredients?The split opinions that come through these first four talks give a good impression of the state of the Italian fine dining situation and I think that in this regard Identità Golose has managed to mirror this without being prejudiced in ether direction. Certainly many Italian chefs, with their inevitable heritage of traditional cooking and its ingredients, have a tendency to approach ingredients in a more conservative way, and in this one also feels the role of Slow food with its Presidia concept. On the other hand, not everyone follows this trend, either using tradition as a base for innovative evolution (like Alajmo) or play with it to subvert it. As I go on with the summary you will definitely see more examples of this.

Thank you for the great writeup. I look forward to more installments and mouthwatering pics!Coming soon

!

! -

The honour of opening the works of Identità Golose was bestowed upon Fulvio Pierangelini, chef and owner of the Gambero Rosso restaurant in San Vincenzo (Livorno). Pierangelini, though little known to most of the foreign public, is widely considered as one of the best –if not the best– Italian cook by the national press: his restaurant has been collecting the top guide awards for over a decade and has two Michelin stars on top of that. Pierangelini himself is known for his timid and brusque character and for his very personal cooking style, made famous by signature dishes such as his passatina di ceci con gamberi (chickpea puree with shrimps) but also by his meticulous study-courses centred on one ingredient such as the three-course piccione arrosto (roast pigeon) or the multi-course (from five to six) study on Maialino di cinta Senese (cinta Senese piglet).

Keeping in character, Pierangelini concentrated on two ingredients he loves: the cinta Senese piglets, and their lard in particular, and eggs. He began by showing a short movie about his pig-breeding facility, were the cinta senese pigs live free and are raised on a diet of nuts and berries from the woods and organic grains. Only once the pigs reach the age of four they are butchered to obtain lardo, pancetta and other cured meats. Pierangelini's aim was that of highlighting the respect and responsibility a chef should show towards meat as an ingredient coming from a living creature.

He then turned to talk about his eggs from Livornese race hens, product of a failed experiment. Pierangelini had tried feeding these hens with goat and sheep milk, trying to reproduce the method used in France to raise poulardes de Bresse. Unfortunately the meat obtained thus was incredibly tough; surprisingly the eggs the hens produced on this special diet were rich with vanilla and almond aromas.

Pierangelini then presented a series of dishes focusing on these ingredients: fried eggs with lard (above); crusted eggs with lard ice-cream and stripes of candied lard; lard and ricotta ravioli with lard zabaglione and balsamic vinegar; rosemary and thyme cream with lard , gold, cocoa, cinnamon and Sichuan pepper chocolate roulades. To describe his own cooking he declared that: “Great cooking is made of virtuous steps more than technology. What I’m looking for is pushing ingredients to the limit in a natural way, a more intimate relationship with nature. In this congresses we talk about new techniques and unusual ingredients; in contrast I want to show the sense of simple things, because egg is the countryside”

Pierangelini was followed on stage by the first international guest, Pascal Barbot of L'Astrance in Paris. Barbot, according to some “the new face of French”, grew professionally in the kitchen of Alain Passard before starting up his own place at the turn of the century. In a few years his unique cooking style has managed to win him two Michelin stars and the Gault Millau prize for best French chef in 2005.

Barbot focused on the inspirations he extracts from his travels around the world and demonstrated this trough three dishes. His “Retour du Japon” (above) is an eggplant, miso and chocolate dish, a simultaneous homage to the classical combinations of eggplants in the Japanese (miso) and Italian (chocolate) cooking and to French techniques (lacquering). “Retour des Indes” is his take on spices in a sauce which investigates the results of different cooking times for curry. Finally Barbot demoed “Retour de Chine”, were he explored the opportunities offered by a soup at the end of a meal, also with a digestive goal in mind.